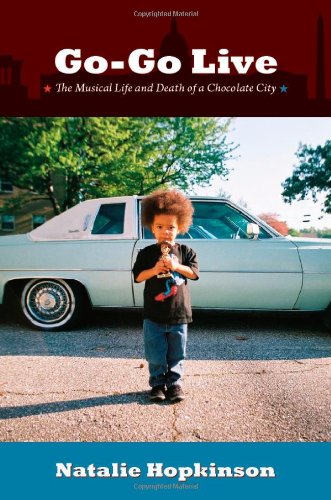

Singer and guitarist Chuck Brown invented go-go music in mid-’70s Washington, DC; it was an infectious blend of funk, Latin rhythms, and audience call-and-response that became the sound of African-American DC for decades. By the time of Brown’s death in May at age seventy-five, he had become the undisputed godfather of the genre, and a civic icon, even though go-go never found much of an audience outside the capital city. At Brown’s funeral, DC Council chairman Kwame Brown (no relation) began his eulogy in a defiant tone. “I am go-go,” he declared. “To the media, you better get that right. For all the people who just moved to Washington, DC, and have a problem with go-go music, get over it.” Taken literally, the exhortation made little sense. As a metaphor and piece of political theater, though, Brown’s statement was powerful (especially since he was then under investigation for fraud). A year earlier, the Census Bureau reported that the city had lost its black majority for the first time since 1957; between 2001 and 2011, the white population had grown by 31 percent. So Brown was tapping into a deep vein of discontent as he branded himself with a homegrown black symbol of bygone days.

As it turned out, that funeral was nearly as fraught with racial and political implications as the 2010 memorial service for another go-go pioneer, Rare Essence founder Anthony “Little Benny” Harley, described in the first chapter of Natalie Hopkinson’s study Go-Go Live. Hopkinson’s book is part requiem for a culture that she sees being cast aside by a changing DC, and part appreciation of its unlikely survival and evolution. Her interviewees are full of rich stories, and the book is at its best when she lets them do the talking—such as in a chapter entirely given over to a dialogue with “Grandview Ron,” a DC resident with deep ties to go-go, or the last chapter, “Roll Call,” an annotated transcription of a 1986 Rare Essence show. At times, her somewhat clinical and academic tone clashes with the improvisational, raucous nature of her subject—especially in places like the long, detailed footnotes that accompany spontaneous shout-outs recorded at the Rare Essence show. (“The Dom Perignon crew was a well-known local crew whose members were major patrons of go-go. The crew took the name of . . . the French champagne brand named for a seventeenth-century monk.”) At Little Benny’s funeral Hopkinson asks a mourner, “So . . . are you a go-go fan?” eliciting this baffled response: “Am I a fan? That’s a strange thing to ask. . . . That’s like asking someone from New Orleans if they like jazz. It is them.” The service was five months before DC’s 2010 mayoral election, which saw the city split sharply on racial lines even though the political divide was between two black DC natives. The crowd booed incumbent mayor Adrian Fenty (who wound up losing the election) for being too cozy with developers gentrifying historically black neighborhoods. Two years later, the celebration of Chuck Brown’s life that took over the city felt more like a wake for the black DC that had fostered go-go culture than a memorial observance for the genre’s inventor.

Hopkinson writes that the music had “flourished both because of and in spite of the decades of adversity that preceded [DC’s 1968] riots and intensified after them. Go-go established musical spaces in the ruins of social upheaval: in crumbling historic performance spaces such as the Howard Theatre, in hole-in-the-wall nightclubs such as the Maverick Room; in backyards, community centers, and parks.” Not just bands and clubs, but music labels, record stores, and clothing brands all sprang up to serve go-go’s fans. Almost all of these businesses were owned and operated by black entrepreneurs. None had anything like the success that hip-hop culture—born around the same time as go-go—would have, although that seemed beside the point. As Hopkinson writes, go-go never sold out, never crossed over, never left its black roots. Dice, a nineteen-year-old member of the go-go–reggae band INI, tells Hopkinson: “It’s more music of the struggle. It’s more the gutter sound. In most of the neighborhoods, everybody’s poor. Everybody’s struggling. Go-go doesn’t go mainstream.”

At the center of the scene was Club U, a nightclub in an old government-owned building that hosted weekly go-go concerts until it closed in 2005. When the venue first opened in 1992, the historic U Street neighborhood was still recovering from the 1968 riots; Club U was part of a revitalization effort to bring in some foot traffic. It worked—maybe too well. These days, apartments rent for two thousand dollars or more a month in buildings such as the Ellington (named for the great DC-born jazz innovator). Frequent violence at the club didn’t help its chances for survival, but Hopkinson suggests that the city’s demographic changes might have doomed it anyway. “The Chocolate City is dying,” she writes, referring to black DC by a nickname, coined in a 1975 Parliament song and album of the same name, that was taken up with pride among DC’s black majority. In the 1970s, when go-go was starting to take off, the city’s white population had dwindled to barely 25 percent. Chocolate City was DC.

She might be right: It may well be dying now, after all. This spring, though, tributes to Chuck Brown aired on local TV, along with go-go concerts, and crowds gathered and chanted one of Brown’s most famous refrains: “Wind me up, Chuck!” It seemed like DC might find a way to keep the beat going a little while longer.

Mike Madden is editor of the Washington City Paper.