When I was eleven years old, my room was a shrine to the New York City sports stars of the 1980s. The posters on my wall included the Giants’ fearsome linebacker Lawrence Taylor, the Knicks’ quicksilver forward Bernard King, and the Mets’ triumvirate of awesomeness: first baseman Keith Hernandez, outfielder Darryl Strawberry, and their phenomenal nineteen-year-old pitcher Dwight Gooden. I imitated their every move on the field, and fantasized—in an elementary-school-boy fashion—about their lives off the field. What I didn’t know was that all of these athletes had serious love affairs with cocaine. In retrospect, it was like having posters of the Scarface all-stars. Over the next few years, LT went to rehab, as did Darryl and Doc Gooden. Bernard admitted his past drug use, and Keith had to testify in a high-profile cocaine trial. My mother told me to take down the posters, and in my first act of obnoxious rebellion, I said, “Hell no.” I was being irrational, which I remember understanding at the time, but I just didn’t care if these athletes had problems when they were out of uniform. I knew who they were on the field—nothing less than supernatural beings, gods among men.

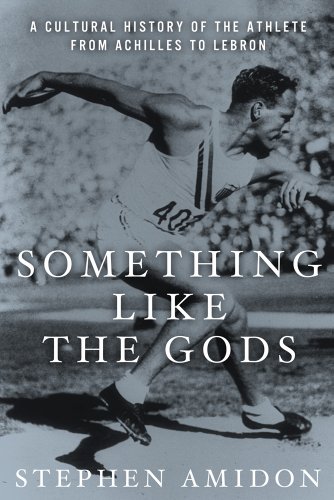

This penchant for placing athletes on platinum pedestals has skyrocketed over the last thirty years. How did we come to view athletes in a holy light? Stephen Amidon’s Something Like the Gods supplies straightforward and engaging answers. After reading it, I feel less crazy for my youthful enthusiasms, less sheepish, and less like I was a sheep—I was actually caught up in an idea that stretches back across the ages: seeing something transcendent in the prowess of accomplished athletes. Amidon—an author with half a dozen novels and a few nonfiction titles to his credit—has produced a short survey of this large subject, but also one with uncommon depth. He makes good on the title’s promise by taking stock of celebrated sports figures throughout history: from spear-throwers seventy-two thousand years ago (who represent the first practitioners of sport), to the ancient Greeks, all the way up to twenty-first-century South Beach—home of galactic basketball demigod LeBron James. Amidon’s great contribution is that he doesn’t merely focus on the changes wrought in the idea of the athletic icon; instead he emphasizes continuity: “The line from the hunter’s club to the Louisville Slugger might be a long one, but it is also unbroken,” he writes.

This unbroken line is not surprising, Amidon notes, since sports are consistently a reflection of the forces roiling the broader society; they “represent the ethos of [an] era.” He expertly teases out the malleability of our idea of athletic icons as they constantly shape-shift to suit the cultural norms of their time. Within the twentieth century alone, the archetype of the athlete has mutated dramatically, first representing the pastimes of white male aristocrats, and then coming gradually to include people of color and women, as well as less privileged competitors. The model sportsman, in short, has transformed over the past century from the “gentleman amateur” (think Teddy Roosevelt) to the contract-savvy teenager with an agent, wheeling and dealing in a trillion-dollar global business (think Dwight Howard).

There is no way Achilles would ever recognize a fellow athlete in Teddy Roosevelt, who would never hope to understand a Billie Jean King, who would, in turn, have difficulty relating to a LeBron James—yet these icons share a unique position in human society. Each of them is, as Amidon writes, “a figure who bridged the gap between the sacred and the secular.” The power of sports is less the power to “brainwash” or be “the opiate of the masses” than it is, Amidon writes, the “power to provoke awe,” which he shows repeatedly “has not diminished.”

This point comes across particularly sharply in Amidon’s chapter “Shirts vs. Skins,” about the trials faced by all athletes of color, with a focus on the American black athlete in particular. When Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists in a Black Power salute at the 1968 Olympics, when an athlete from a colonized nation—where sports are often used to pacify dissent—excels at a Western sport, or when LeBron James opined that race might be a factor in the vehemence of the backlash against him for leaving his hometown Cleveland Cavaliers, we see that “their skin has always placed expectations on them above and beyond anything demanded of white players.” While their elite status allows them to make indelible statements, they often become casualties of the “burden or blessing”—as former NBA player Etan Thomas phrased it—of being expected to play the game well and represent their race. Still, even the most radical acts, such as Smith and Carlos’s defiant salute, can be co-opted into generic images of sports’ panoramic grandeur. (At the 2012 Olympics’ closing ceremony, the Spice Girls performed a clenched-fist salute.) Too often the message is lost while an idealized image remains—and the individual athlete suffers for it. By identifying the continuity and the changes over aeons of history in a style that is amusing and deft, Amidon succeeds where many have failed: He’s written a critical history of sports that also captures what exactly attracts us to these games in the first place.

Dave Zirin’s most recent book is The John Carlos Story: The Sports Moment That Changed the World (Haymarket, 2011), which was nominated for an NAACP Image Award.