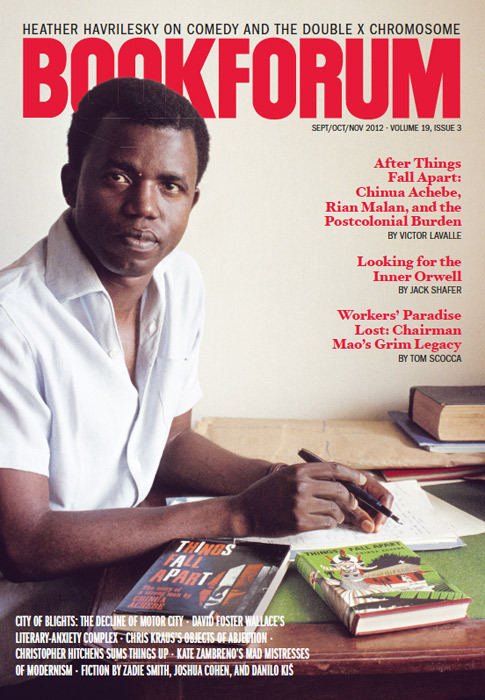

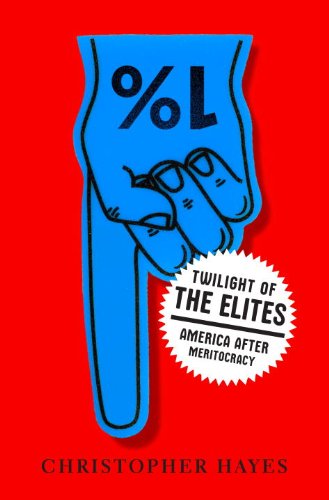

I opened Twilight of the Elites with some skepticism—not so much out of any quarrel I had with its argument as from worries that stemmed from the conditions of its production. It’s certainly true, as Nation correspondent Chris Hayes argues here, that growing numbers of Americans who’ve worked hard and played by the rules, as Bill Clinton put it, are deciding that the rules have been rigged—by Clinton as well as others—and that something’s wrong with the game itself. But we’re rarely driven to develop such thoughts further, in large part because our income, support networks, cultural tastes, and even self-esteem are so bound up with the juggernaut of casino-finance capitalism that even rumors of its failure generate bull markets in prophecies of doom more often than they spark protests.

These days, there’s nearly as much profit to be made in betting on democracy’s devastation as in turning real estate into unreal estate. Lenin allegedly said that capitalists will sell you even the rope to hang them with, but will they market determined efforts to get us out of this? Can “Down with capitalism!” become “Up with Chris Hayes!,” the title of the MSNBC show hosted by the author of Twilight of the Elites?

When I first read Hayes’s claim that winning power now requires not courage, discipline, the force of a better argument, or a working love of democracy, but only three baleful preconditions—money, platforms for attracting paying audiences, and assiduous networking that certifies one as part of the elite—I wondered if this was an indictment of others or a blueprint for the fledgling career of a certain cable-news pundit. If the latter, where’s his prescription taking him—and the rest of us?

“Platform,” he tells us, “is a term I first learned from the publishing industry, where the sales potential of a given author is judged largely as a function of how many people (and how many People Who Matter) a given author can reach.” If money is speech, you must convince the keepers of a platform that your speech will bring them money by attracting viewers for their commercials. Only then might a publisher think you’ll attract book buyers, too.

So now Hayes has a place on the platform at MSNBC, a subdivision of a conglomerate that has found a market for fighting Fox News’ fire with more fire. We can be glad of that, but MSNBC isn’t doing it out of political conviction; the network’s hosts occupy its platform for only as long as they continue to attract eyeballs perched thirty inches above credit cards. If there’s no disciplined thinking or deep feeling in between, all the better for the sponsors; if the cable hosts don’t shout, the ratings suffer.

Hoping to dignify such dubious celebrity, some of them write books. Hayes notes that Rush Limbaugh and Bill O’Reilly use their platforms to “turn out books that . . . dominate the New York Times bestseller list.” Again, it’s not entirely clear whether this is an indictment or a prescription: Unlike Limbaugh or O’Reilly, Hayes is a real writer, but, by his own logic, he has relied on one conglomerate’s platform to enable him to publish his book with another, a division of the Random House corporation.

He presents himself as the son of a community organizer and a civil servant in East Harlem and tells us he got onto the rickety tower of meritocracy after testing into the supercompetitive feeder school of elite Hunter College High School. Only a few of the thousands of smart, hopeful sixth graders who took the same entrance test got to move up with Chris. Hayes argues that this and other disparities supposedly ratified by meritocracy really reflect growing inequality among individuals of different economic circumstances more than they reflect cultural deficits among groups. He largely explains cultural liabilities as consequences of racism and other barriers to economic success.

But Hayes finesses the likelihood that something in his upbringing gave him more cultural “capital” than many of his fellow citizens have been able to access. He doesn’t note that after Hunter he went to the Ivy League, at Brown, or mention Jerome Karabel’s revelatory 2005 book The Chosen, which describes how Ivy colleges have kept defining and redefining “merit” to secure their class prerogatives.

He does zoom in on elite betrayals of public faith in baseball, the Catholic Church, the banking industry—and offers a qualified indictment of his own profession into the bargain. “It takes some willful delusion to blame the media . . . for our predicament” now that so many authorities “have shown themselves to be untrustworthy,” he writes. But he slams journalists whose reporting was skewed by proximity to power, and he names New Yorker editor David Remnick,Slate editor Jacob Weisberg, and Talking Points Memo editor Joshua Micah Marshall as among those gulled into supporting the Iraq war.

Hayes’s explanation for elite failures is that “three decades of accelerating inequality have produced a deformed social order and a set of elites who cannot help but be dysfunctional and corrupt.” But four decades ago, when inequality wasn’t nearly as pronounced and employment and consumption were booming, many Americans bitterly resented elites who’d plunged us into a senseless war and promoted infantilizing modes of consumption and some Great Society projects that provoked a bitter antiwar movement and a tuned-out counterculture, as well as an enraged conservative movement.

Hayes acknowledges that season of deep mistrust, but he argues credibly that today’s elites coddle and one-up one another in habits and assumptions that have proved even more destructive: He offers a quick, memorable send-up of the status-tracking tics of “Very Serious People” at Davos, captives to “a system of incentives that produces an insidious form of corruption.”

His assessment of meritocracy’s deceits would have benefited from a closer look at Mickey Kaus’s 1992 book The End of Equality. Kaus dissects meritocracy’s corruption by standards and procedures that make its certifications of intelligence more dependent on high income—but argues that capitalism per se is less to blame than our failure to limit its reach into every sphere of life. It’s hard to shake the sense that Twilight of the Elites is dependent on the kind of social practices Hayes is indicting.

One reason for such reliance on capital’s ever more intrusive, intimate marketing of desire is that its progressive critics are as committed to “growth” as are the neoliberal architects of the global market. “Why do modern people believe that there will be perpetual economic growth?” asks David W. Noble, whose new book, Debating the End of History, is an account of his break not just with bourgeois economics but with the progressive mythology of humanity’s forward march out of history into stable societies reliant on endless economic expansion.

Noble assails what he considers the conceit, shared by Western thinkers from Plato, Francis Bacon, and Marx through Francis Fukuyama, that as we discover what we think are timeless, stable truths of science and economics, we’ll outgrow the “irrational use of resources by traditional people.”

As Noble renders this myth (so sweepingly, I think, that it’s unfair to Plato, and so often that it’s almost an incantation), legatees of Western thought try incessantly, but in vain, to escape from “an old world of unstable, timeful cultures” into “a new world of stable, timeless nature.” And we’re destroying our finite planet, which Westerners have treated as part of an infinite universe they can master.

Noting that historians are “participants in cultures that gained their meanings from . . . mythic narratives,” Noble tracks the “end of history” delusion in the work of triumphalist historians such as George Bancroft, who thought that humanity’s “exodus from medieval darkness to the light of modernity was caused by the [Protestant] Reformation,” born again in American nation building by confirmed individuals in a pristine, timeless Eden assigned to that purpose by God. Such historians practiced “bourgeois magic” to dispel the despoliation and suffering this brought to “artful, timeful” cultures that knew the earth as a vulnerable organism, not an endlessly exploitable resource.

Equally deluded, Noble writes, were progressive historians and philosophers who foresaw a path to redemption not in pristine, timeless nature but through industrial revolution and science-driven, timeless expansion. Neither American exceptionalists on the right nor American universalists on the left have escaped the illusion of endless growth.

Noble surveys all of Western intellectual and political history, and finds it escapist in its yearning for an exodus by stable, middle-class individuals into comfortable lives beyond the vicissitudes of history. Yet he doesn’t really think we can return humbly to the bosoms of timeful, artful cultures within nature, and his book ends with wan hope, at best: Although the dominant culture still believes “that perpetual growth is normal,” Noble writes, “the visibility of ecology since the 1970s has caused a variety of individuals to convert to a belief that the future will be one of scarcity.”

Like Noble, Hayes foresees a “crisis of catastrophic global climate change,” calling elites “incapable of . . . forestalling the immiseration and destruction that now approach like a meteor.” But unlike Noble, he thinks that global warming or a financial meltdown, while “not something to be longed for,” could discredit corrupt authorities and produce “a tumbling cascade of new forms of politics.” He’s almost counting on this, but he doesn’t discard faith in growth and progress or suggest embracing humbler, more communing ways of life, as Noble urges.

So here he is, on his show on Sunday, July 15, hawking Twilight of the Elites between commercials for depilatory gadgets and adult dating services. He’s had some minutes to grill a former Bain Capital partner who defends corporations’ outsourcing of jobs and the social costs associated with the practice, but these interrogations are disrupted so often by ads that it’s hard to determine whether they’reintended to be more than padding for sales pitches that plunge viewers back into fantasies of endless growth.

Won’t Hayes’s concessions to the circulation of commodities corrupt the circulation of his ideas? Isn’t he becoming a sleek tiger pacing his gilded cage? “Those opposed to the current social order must locate another base of power that can credibly challenge the power of incumbent interests,” he pleads. But what other base? Hayes writes that “the answer lies in a newly radicalized upper middle class” leading “a trans-ideological coalition that . . . marshals insurrectionist sentiment without succumbing to nihilism and manic, paranoid distrust,” and “leverages the deep skepticism of elites into a proactive, constructive vision of a moral, equitable, and connected social order.” That’s pretty much the case that John and Barbara Ehrenreich made in the 1970s for a revolution of the “professional-managerial class”—an exhortation that failed, for reasons that Mickey Kaus offers in The End of Equality: People are all for rubbing shoulders across class lines, but only in spheres that don’t compromise their “rights” to succeed in the markets. What will make them acknowledge the consequences now?

As a TV host, Hayes challenges adversaries like the Bain Capital partner, and, so far, it sells. But Noble wouldn’t be buying. He reminds us that middle-class citizens, instead of facing the truth, are engaging in what Andrew Szasz called an “inverted quarantine” that views “the larger environment as polluted” and exempts them from blame in buying their way into safe havens, whole foods, and personal fitness. “They . . . see themselves as self-made and independent. Implicitly nature must continue to be the timeless foundation for the timeless marketplace.”

Hayes doesn’t take his critique as far as Noble, writing much later in life, has done, despairing not only of elites but of their followers and even most of their critics. To warn against the irresponsibility that Noble despairs of, Hayes has hopped onto the wrecking ball that Noble says is prompting it.

Jim Sleeper is a lecturer in political science at Yale University. His book The Closest of Strangers (Norton, 1990) will be e-published by Norton this fall.