Madeleine L’Engle’s 1962 novel A Wrinkle in Time—one of the best-loved and best-selling children’s books of the past sixty years—was initially rejected by at least two dozen publishers. The story goes that later on, whenever L’Engle attended a literary event, she would carry the rejection letters in her purse. If editors happened to mention to her that they regretted not having had the chance to publish the book, she would whip out the proof that they had passed it up. Like most good stories, this one is probably apocryphal. But it ought to be true, not only because of its poetic justice, but also because it is entirely of a piece with L’Engle’s persona: prone to drama, a little irascible, and always asserting her mastery of her own narrative.

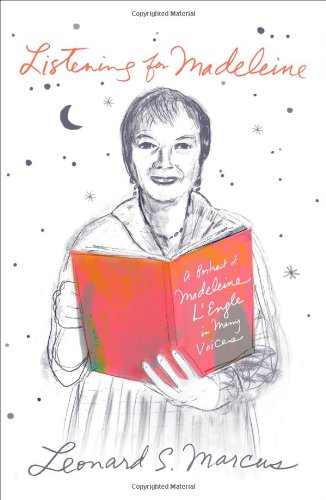

As yet there is no full-length biography of L’Engle, who died in 2007 at age eighty-eight. Those of us who memorized her books as children might wonder who would want to read one. Isn’t Meg Murry, the gawky, headstrong protagonist of A Wrinkle in Time, a self-portrait of L’Engle as the bookish and brilliant adolescent she must have been? And wasn’t the Austin series a chronicle of her adult family life—the New England farmhouse bustling with children, pets, and glamorous friends always coming and going? But Listening for Madeleine, a lightly edited compilation of interviews conducted by Leonard S. Marcus with a variety of people who knew L’Engle, makes clear that the truth was more complicated. Just as reality plays an important role in even L’Engle’s most fantastic fiction, fantasy also tended to intrude on her representations of reality, so that what we imagine to be autobiography is in fact something far less stable.

This is no tell-all: Published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, L’Engle’s longtime home, and featuring several of her editors and publicists, the book has the feel of a Festschrift—a celebratory volume in honor of one of the house’s most beloved writers. (There is also a sense that certain scores are being settled: A number of the interviewees disparage a profile of L’Engle by Cynthia Zarin published in the New Yorker several years ago, which repeated rumors that L’Engle’s husband had been unfaithful.) The L’Engle depicted here is stern but mostly loving, with a thousand endearing quirks and a bold and unorthodox creativity. Her writing studio at one point contained a desk and an electric keyboard, set up with her chair in between them, so that when she got stuck on a book she could swivel around and practice piano to loosen herself up. (She believed that the fingers, like the brain, can think.) Her early modesty—when she and her husband, Hugh Franklin, decided to give up their acting careers and move to Goshen, Connecticut, they bought the local general store and she was known to all as “the grocer’s wife”—ultimately turned into a confidence bordering on arrogance. She was given to dramatic gestures, once threatening to cancel a tour when a bookstore belonging to a beloved friend was left out. Unable to attend a play in which her adult granddaughter was performing, she sent a fur coat as a gift instead.

She also was passionately religious, a practicing Episcopalian who served for several decades as the house librarian at the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine. One of Marcus’s interviewees recalls glancing at L’Engle’s notebook during a meeting to discover that she was writing a prayer. Another person calls her the greatest preacher he had ever heard. Her piety should not come as a surprise: A Wrinkle in Time is a fairly obvious allegory of the struggle between good and evil, and the Austin chronicles allude often to the family’s Christianity. One of L’Engle’s editors muses that her books always reflected “her very deep faith . . . embedded in a great story with great characters,” but the reverse can also be true: L’Engle’s characters are embedded in her faith, which is the real raison d’être of her novels. She liked to speak of her writing as an “incarnational act,” an inseparable part of her religious life.

L’Engle’s faith was deeply untraditional. A mathematics professor who advised her on A Wrinkle in Time says the three beings who guide Meg on her interplanetary journey—Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Who, and Mrs Which—were meant to be angels, but they could just as easily be mistaken for witches. And the novel’s dominant image of evil is an undefined blackness that casts its shadow across a wide band of the universe, including Earth. Camazotz, a planet controlled by the blackness, is not a hotbed of violence and depravity but a vision of perfect order. All the houses are identical, the children bounce their balls in perfect unison, and anyone who refuses to submit to the program is punished. “I am freedom from all responsibility,” the evil power croons to Meg. But she recognizes that this is a false consolation, a substitution of conformity for equality. “Like and equal are not the same thing at all!” she screams.

The fundamental lesson is that it’s OK—even desirable—to be a misfit. (Needless to say, this must be why L’Engle’s books are so beloved by children who are misfits.) Meg suffers at school for being stubborn and independent-minded, but those are precisely the qualities that will serve her so well on Camazotz. One becomes a misfit by exercising one’s free will and refusing to conform to external expectations. “Freedom from all responsibility,” after all, is the fantasy of an adult, not of a child, who longs to be trusted to make decisions for herself.

But it’s not independence alone that allows Meg to assert herself; it’s also her education, which thus far (and she’s barely begun high school!) has included a substantial grounding in literature and philosophy in addition to science and math. Throughout history, Mrs Whatsit explains, the people who have fought against the darkness include not only Jesus but also Leonardo, Michelangelo, Shakespeare, Bach, Einstein, and so on. L’Engle’s passionate humanism pops up again and again in her novels, especially in the Austin family chronicles, where someone always seems to be practicing Beethoven or quoting John Donne. Part of the books’ purpose is didactic: L’Engle is educating children who haven’t yet had that kind of exposure to art and books and music, just as the Austin children themselves educate their own less fortunate friends. As a child whose parents didn’t listen to Schönberg or read Mark Twain aloud at bedtime, I gobbled all this as ravenously as the Austin kids devour the homey dishes their mother always seems to have in the oven. But looking back on it as an adult, the Austins’ “happy and noisy and comfortable” life seems less aspirational than blatantly idealized.

Many readers have assumed the Austin chronicles to be a depiction of L’Engle’s own family. Indeed, when L’Engle showed visitors around her Connecticut house and grounds, she delighted in pointing out landmarks from the books, such as the stargazing rock where the Austins gather on summer nights. But L’Engle’s children and grandchildren confirm that the Austins were a conception nearly as fantastic as the tesseract that allows time and space to “wrinkle.” Charlotte Jones Voiklis, L’Engle’s youngest granddaughter, tells Marcus somewhat bitterly that the books were a “carnival-mirror version of our own family.” Much about the Austins seems too good to be true—the way they spontaneously break out into a four-part hymn during a picnic on the mountain, or the smug confession by Vicky, the eldest daughter and narrator, that “we seem to watch a lot less television than most of our friends.”

L’Engle often said that both Meg Murry and Vicky Austin were versions of herself as a child. But Vicky’s mother, too, seems to be a version of L’Engle: the mother she wished she could be. Her eldest daughter, Josephine Jones, says that her mother began writing A Wrinkle in Time during a cross-country trip the family took before moving back to New York City from Connecticut. The trip, with some of its adventures intact, appears in The Moon by Night (1963), the second book in the Austin series. But the mother in the Austin books isn’t a writer. There’s no mention of her sneaking off to spend time with her manuscript; she’s hanging out with her kids, roasting marshmallows. If L’Engle intended the books to depict her own family, this is a telling alteration.

And L’Engle also seems to have used the Austins somewhat crudely to work out real-life difficulties. At the start of Meet the Austins (1960), the first book in the series, the family adopts the daughter of a friend after both her parents have died. Initially, the girl is spoiled and dreadful, but she gradually succumbs to the civilizing influence of the Austins—just in time to be adopted by someone else. Voiklis and some of the other interviewees comment on the cruelty of this plotline to L’Engle’s adopted daughter, Maria, who came into the family at age seven under similar circumstances, and declined to be interviewed by Marcus. L’Engle’s accumulation in later life of a vast group of informal adoptees—students or fans whom she would mentor and support—may have been an attempt to make up for the attention that she worried she denied her own family. “Madeleine and Hugh ‘collected’ children,” one of their close friends tells Marcus. Their framed photographs filled a wall in the couple’s Upper West Side apartment.

In A Wrinkle in Time, Meg’s mother explains that the sudden arrival of Mrs Whatsit did not surprise her because she is able to have “a willing suspension of disbelief.” The phrase comes from Coleridge, who suggested that a little reality infused into a fantastical narrative helped to convince the reader—a lesson L’Engle learned well. The suspension of disbelief is also what links literature and religion, both of which require a leap of faith as the first step. L’Engle’s friends often describe her as “open to grace”—the chance encounter or random sign that offers an entryway to mystery. It’s a quality that most of us start with and gradually lose. Her faith-based novels may now sometimes seem to go too far, either into the fantastic realistic or the realistic fantastic. But back when we needed them, they were just right.

Ruth Franklin, a contributing editor at the New Republic, is currently a fellow at the Cullman Center for Scholars and Writers at the New York Public Library.