At the end of the summer of 1892, three young and feverishly idealistic Russian immigrants, whose hopes for living in a free and just society had been crushed by their experiences in the Lower East Side slums of Manhattan, were operating a successful ice-cream parlor in Worcester, Massachusetts. They wanted to save enough money to return to Russia, where they believed revolution was imminent.

But they shifted plans when they got word of pending labor unrest in Homestead, Pennsylvania. After three months of failed negotiations over a wage increase, the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers had been locked out of the Carnegie steel mill on the orders of Henry Clay Frick, the manager of the Homestead facility and chairman of the board of Carnegie Steel. After she saw a newspaper headline announcing the lockout, Emma Goldman rushed home from the ice-cream parlor to tell her two comrades (and lovers), Alexander Berkman and Modest Stein, that revolution was coming to America, that they must go to Homestead, not Russia. In the brief time since their arrival in the United States (Goldman emigrated in 1886, when she was sixteen years old, Berkman in 1888, at age seventeen), Goldman and Berkman had already won reputations as skillful agitators in anarchist circles, and they thrilled at the thought of spreading, as Goldman put it, their “great message and helping [the strikers] see that it was not only for the moment that they must strike, but for all time, for a free life, for anarchism.” They decided to return to New York the next day.

As soon as they were settled, they drafted a manifesto titled “Labor Awaken.” But the conflict at Homestead had already escalated. On July 2, Frick discharged the mill’s entire workforce—close to four thousand men; in response, they declared a strike and sealed off the mill to prevent scab workers from entering. Three days later, Frick arranged to surreptitiously transport several hundred Pinkerton guards to put down the strike. The plot was discovered when a contingent of workers, in the early morning hours, spotted barges making their way up the Monongahela River. Armed workers ambushed the barges, and a terrible twelve-hour battle raged until the Pinkertons surrendered. At least six workers and three Pinkertons were killed, and dozens of Pinkertons were reportedly wounded. As the defeated Pinkertons were forced to march into town, a furious crowd of strikers’ wives descended on them; as the New York Times reported, the women “not only used their fists, but clubs, stones, bricks, broomsticks, mop-handles, and any missile upon which they could lay their hands.” And workers across the country likewise rallied to the cause; ninety thousand laborers in Chicago alone celebrated “Homestead Day” with a walkout of their own and sent forty thousand dollars to the Homestead strikers.

Popular sentiment was aligning behind the strikers—until, that is, Frick and company prevailed on the state to intervene. On July 12, the governor of Pennsylvania sent the entire state militia—8,500 men with a cavalry detachment and field guns—to restore order. For the next five months, Homestead was under martial law; families were forced out of their company-owned homes, and two thousand replacement laborers, under the militia’s protection, were brought in to run the mill.

When Berkman, Goldman, and Stein learned of the bloody battle between the strikers and Frick’s hired army, they knew the time for their manifesto had passed and they would have to take more extreme action, which for them meant only one thing—attentat, aka “propaganda by the deed.” The idea was for Berkman to assassinate Frick; this, they believed, would spark a larger workers’ revolution. After a number of mishaps, on July 23, Berkman forced his way into Frick’s office, shot him twice, and then, as Frick tried to fend him off, repeatedly stabbed him. Workers rushed into the office, tackled Berkman, and furiously beat him, pinning him down until the police arrived.

Miraculously, Frick survived the attack, but Berkman’s reckless plunge into attentat still raises a larger historical question: What drives a man to act with such calculated ruthlessness, and to ask in all earnestness (as Berkman did at the time), “Could anything be more noble than to die for a grand, a sublime Cause?” These wildly misguided idealists justified the attempt on Frick’s life by regarding him, as Goldman put it, not “as a man, but as the enemy of labor,” “antisocial and antihuman,” “the perpetrator of coldblooded murder.” Berkman went so far as to declare that “to remove a tyrant is an act of liberation, the giving of life and opportunity to an oppressed people.” (Stein, meanwhile, was still in the grip of the plot after Berkman’s arrest—he set out to finish off Frick with a bomb, but dumped the dynamite he held in his pockets when he saw a newspaper headline announcing his attack-in-progress. He would eventually pursue a successful career as a pulp-magazine illustrator.)

In such declarations, Berkman and Goldman were applying—or misapplying—lessons they had learned during their youths under the tyranny of czarist Russia, where public protest and even criticism were punished by long prison terms, exile, or execution, leaving those seeking to right economic and political inequalities only the most dramatic, violent gestures.

Equally important in shaping their imaginations were the examples of heroic martyrs presented in the great Russian literature of the time—Turgenev, Dostoyevsky, and Tolstoy. The character who impressed them most deeply was the hard, austere, intensely disciplined, and single-minded revolutionary Rakhmetov in Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s novel What Is to Be Done?—so much so that as Berkman prepared to carry out Frick’s assassination, he took “Rakhmetov” as his alias.

Berkman and Goldman badly miscalculated the state of opinion in their adopted country. Even though great numbers of workers had experienced and rebelled against the inequalities and humiliations of industrial capitalism—there were tens of thousands of industrial strikes involving hundreds of thousands of workers in 1877, 1886, and 1892–93, the peak years of labor revolt during the Gilded Age—few Americans were prepared to endorse assassination as a legitimate means in the workers’ fight for justice. The newspapers assailed Berkman’s action; the public, which had initially been hostile to Frick, now expressed sympathy toward him. Homestead strikers and labor-union leaders denounced Berkman, and arguments raged in anarchist circles concerning whether violence alienated American workers from their shared cause.

Berkman, who refused representation by an attorney since anarchists regarded the law as a tool of the corrupt capitalist state, was tried in secrecy. The jury did not feel it necessary to leave the jury box and convicted him on the spot. The entire proceeding took less than four hours, and the twenty-one-year-old Berkman was sentenced to twenty-two years in prison. Known anarchists in Pennsylvania were arrested as coconspirators; Goldman, for her part, came under suspicion, but there was not enough evidence to link her to the plot.

After Berkman’s conviction, Goldman devoted herself to vindicating him and his action, delivering lectures across the country about the moral necessity of political violence. Her passion and mesmerizing style won her fame among various progressive groups, and Goldman became a highly sought-after speaker not only on the subject of anarchism but also labor, free speech, free love, and birth control. In 1899, for instance, she undertook a punishing eight-month speaking tour, visiting sixty cities and towns, delivering 210 lectures to more than fifty thousand people. When Leon Czolgosz carried out his successful assassination of President William McKinley in Buffalo, New York, in 1901, he claimed that Goldman inspired him to act; in short order, the press labeled Red Emma “the most dangerous woman in America.”

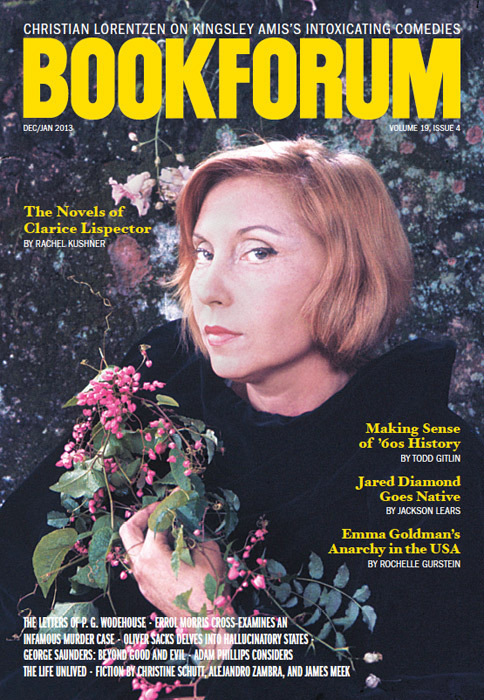

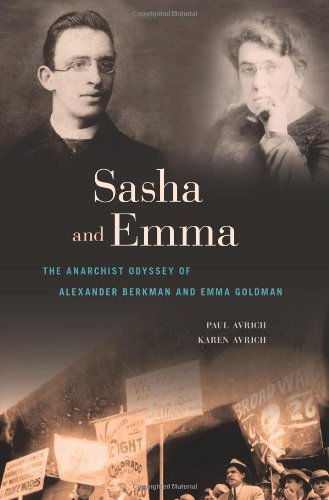

For the rest of their lives, as Karen Avrich recounts in the gripping dual biography Sasha and Emma, Berkman and Goldman were impassioned agitators, helping to give shape to what we now think of as the tradition of anticapitalist dissent. In 1906, attorneys for Berkman, then thirty-five, won him an early release from prison, but only after he had been subject to fourteen years of backbreaking labor, repeated starvation diets, and stints in solitary confinement. Broken and alienated, Berkman, with Goldman’s help (though they were now only comrades and not lovers), rebuilt his life, lecturing across the country about the brutalizing conditions of prison, eventually publishing his gripping Prison Memoirs of an Anarchist in 1912. Working separately and together, Berkman and Goldman were at the center of virtually every radical cause and action of the time—a collaboration that also kept them under the watchful gaze of the state and the police. And after the United States entered World War I, President Woodrow Wilson signed the Espionage Act—which empowered the United States to deport Berkman and Goldman (along with thousands of other immigrant radicals) back to their Russian homeland after they had been rounded up and jailed for speaking out against conscription and the war.

Once they were resettled in Bolshevik Russia, their lifelong hopes for a free and just society collapsed as they were confronted by brutal suppression of all dissent, including the imprisonment, torture, and execution of anarchists. Convinced the revolution had been betrayed, they managed to escape to Sweden in 1922, which marked the beginning of their exile in Berlin, Paris, London, and the South of France, sometimes living together, more often living apart, but always in constant and loving correspondence. Their public condemnation of the Russian Revolution earned them the wrath of radicals worldwide, and even though they continued as agitators and polemicists, they found it increasingly difficult to reach audiences, and, in turn, to make a living. Berkman committed suicide in 1936 after learning he had cancer; Goldman died of a stroke in Canada four years later.

The epic struggles of Berkman and Goldman have filled many admiring volumes of leftist history. Avrich’s new and comprehensive account is more than a memorial for her subjects; it is also a tribute to her late father, Paul Avrich, the premier historian of anarchist movements in America and Russia. The elder Avrich had collected copious materials for a draft version of this dual biography, but he had been unable to complete it before his death in 2006. Karen Avrich’s skilled editorial guidance delivers the full dramatic sweep that the subjects of Sasha and Emma demand, and beyond that, the book’s central strength is that it gives Berkman a place of equal prominence to Goldman, who, largely because she was rediscovered in the 1970s as a feminist “foremother,” has sparked far greater critical assessment.

Still, one greets this larger-than-life study of the modern revolutionary’s vocation with a certain puzzlement—a kind of variation on the age-old radical quandary “What is to be done?” While reading Avrich’s excellent chronicle of Berkman and Goldman’s lives and times, I was once again moved by the depth of their idealism and commitment—but I was also repeatedly struck by how different our current situation is from theirs. Their experience of injustice and inequality was tangible. It meant something to speak, as Goldman and Berkman did, of “parasitic capitalists,” “capitalistic thieves and idlers,” in a world where labor truly was “the creator of all the wealth in the world,” where “everything in this city was created by our hands or the hands of our brothers and sisters.” Amid the present-day polarization of wealth, however, such evocations of a shared historical plight among the dispossessed, rare as they are, have little resonance. Thanks to the steady financialization of the economy and the export of manufacturing jobs to the impoverished developing world, fewer and fewer of us make anything—and certainly not under the exploitative conditions of the nineteenth-century factory. And this radical change in our everyday lives appears to have sharply weakened, if not altogether severed, our direct relationship to the rich.

As a result, the experience of injustice seems to impress us through a glass darkly—as do most proposals to remedy it. Almost daily we are confronted with the well-known but lifeless statistic that the top 1 percent of the population possesses a greater collective worth than the entire bottom 90 percent. But most of us in the bottom 90 percent are not working for the 1 percent, and they are not getting rich from the labor we perform. In truth, we have a hard time understanding where their mind-boggling riches come from, let alone what we can do to bring about a more equitable society. It was one thing for workers to revolt in order to remedy shared grievances against “parasitic capitalists” backed by their private armies and state militias—especially when they could count on support from their communities and like-minded labor unions across the country. But how does the diffuse, atomized “bottom 90 percent”—or the “99 percent” that Occupy Wall Street has made its rallying cry—come together to act against the equally abstract “top 1 percent”? What is the foundation for solidarity and revolt now that we live in a postindustrial society?

There is obviously no ready answer to such questions. Berkman’s propaganda by the deed backfired in important ways by forcing Americans to confront a species of political violence that seemed alien to their democratic institutions and constitutional tradition. And by vilifying Frick—who had arranged to kill strikers in Homestead—Goldman and Berkman made the industrial-age labor conflict an all-consuming personal crusade. Now, by contrast, we find a growing spirit of unrest taking root amid conditions that we can clearly see are going from bad to worse; nonetheless, it is unable to fasten on to a particular flesh-and-blood person, let alone someone who might plausibly be characterized as a class enemy. Perhaps people are only willing to act in concert with others when they experience something that affects them personally; that may be why the period of greatest political activism in America—at least so far—coincided with the period when millions of men and women first experienced the miserable conditions of the industrial labor system.

Rochelle Gurstein is the author of The Repeal of Reticence (Hill & Wang, 1996).