What do we make of the adjective poetic when applied to prose fiction? While meant as praise, the modifier often sways backhandedly—as eclectic does for a menu—warning that what’s ahead may prove puzzling at best or downright indigestible at worst. Certainly the description indicates the presence of typical techniques—rhythm, alliteration, figurative language, and the like—as well as a density of both locution and imagery. But when used to characterize prose, on book jackets or in reviews, there’s an abiding sense the word also signals effeteness and self-indulgence: This is no mere page-turner you’re holding. Christine Schutt—author of the short-story collections Nightwork (1996) and A Day, a Night, Another Day, Summer (2006) and two novels, Florida (2004) and All Souls (2008)—has been tagged with this adjective throughout her career. Indeed, quotes from John Ashbery, who selected Nightwork as a best book of the year for the Times Literary Supplement in 1996, can be found among her blurbs. And the much-lauded author (National Book Award nomination, recipient of a Pushcart Prize and a Guggenheim, and a finalist for a Pulitzer) has done rather nicely despite the designation’s ambiguities. Still, it bears pondering, just what is this hybrid blossom, poetic prose, and how is Schutt’s fiction—rather commonly themed around incest, emotional disturbance, marital dissolution—particularly different for its presence in her pages?

Florida, Schutt’s first novel, was turned down by numerous publishers—no doubt because of its unconventional style. In short vignettes Alice, the narrator, recalls a troubled childhood with her mentally unstable mother from the vantage of adulthood. Her recollections—pointed, nearly always epiphanic in their closing lines—arrive like tiny sculptures hand-delivered to gallery pedestals, rather than borne by the more fluid, if not torrential, pacing that often marks memoiristic novels. The therapist’s drape-drawn chamber isn’t their point of origin; they appear to have emerged from a clean, well-lit atelier. Focused on a limited field of action, structurally self-contained, each chapter generates a knowing, utterly self-conscious atmosphere where not only memories but memory itself seem scrutinized by the language that brings them to life, as when Alice recalls the night before her mother was institutionalized:

I attended to the drama of Mother’s clothes, the smoke-thin nightgown she wore before Arthur came; I wanted it. She wisped through the house in this nightgown and eschewed electric light and carried candles. “Go to sleep,” she had said, come upon me spying, and I said to her, “You, too!” but Mother was awake and moving through the house and out across the snow—Mother shouting back at me, “You’re not invited!” Later, she cried, and I sat under the crooked roof of her arm and felt her gagged and heaving sorrow. “If your father were here . . .”

The diction, imagery, the entire scene are rendered with a precision that both undermines and amplifies a sense of emotional authenticity; if painterly effect mutes the confessional urgency, it also sharpens its aim. The alliteration (“eschewed electric,” “carried candles”), figuration (“smoke-thin nightgown”), and the overall tableau vivant of this wraithlike woman moving “across”—not “in,” somehow she appears to be aloft—the snow all conspire against our recognizing this moment as truly lived. Alice’s own turbulence at the time, as well as in the act of recollecting, recedes with vividness. It’s a stage set—doubly artificial for being rendered in heightened language.

That said, the passage, like so many others in Florida, sounds out essential feelings, their intricacies and internal conflicts, via that stagecraft. Schutt works surprise and dislocation into the midst of efficient description to piercing effect: The plaintive “I wanted it” in the wake of the elegantly turned “smoke-thin nightgown,” or the aptly architectural “crooked roof of her arm” preceding the guttural “gagged and heaving sorrow”—these micro-contrasts in tone and imagery ably mimic consciousness at its most alert, most mutable, in short, most transcendent. The shifts set off tiny detonations that build in much the way that, say, a sonnet assembles revelations toward its clinching couplet. In Schutt, the poetic in her prose is not the obvious lyricism and compression, but their relation to the mundane and the broadness of plainspoken expression. When these juxtapositions succeed, she performs what Baudelaire, in the preface to Paris Spleen, calls the “miracle of a poetic prose,” writing that’s “musical though rhythmless and rhymeless, flexible yet rugged enough to identify with the lyrical impulses of the soul, the ebbs and flow of reverie, the pangs of conscience.”

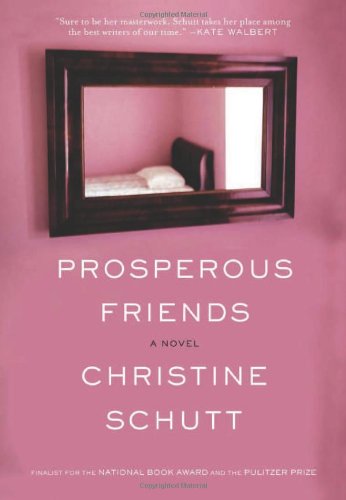

A similar disposition to illuminate peaks of cognizance amid humdrum circumstance invests Schutt’s latest novel, Prosperous Friends, with an almost electrical charge, even if its plot involves pretty standard-issue jealousies, longings, and infidelities. Schutt introduces Ned Bourne and Isabel Stark, young marrieds who hail from deep within the leisure class and possess of many of its appurtenances: Ivy League degrees, tennis proficiency, a TriBeCa loft, and, of course, the titular well-to-do friends. Their story proceeds episodically over the course of about two years: We encounter them in London, where Ned has a postdoctoral fellowship and is writing a book of short stories; then in downtown Manhattan—theater nights, publishing lunches; and, finally, at the summer home of the famous painter Clive Harris and his poet wife, Dinah. Along the way their marriage falls prey to sexual incompatibility, unfulfilled longing, and a kind of generalized anomie. The legalism “alienation of affection” quite captures their dismal couplings:

Afterward, the only thing he could say was he wanted to give her pleasure.

“Not that way, you don’t.”

She showered in a plugged-up tub, then sat growing colder in the scum that was water.

Glum Isabel trying to cleanse in a gray puddle—that’s the author’s sure-handed touch at creating images that register those “pangs of conscience” with indelible force. Schutt has a delicate eye for the visceral. Like a Pre-Raphaelite painter, she shines unnatural light on natural things to disconcert and unbalance viewers. Mostly this pictorial, metaphor-making skill serves her characters and their situations, but occasionally the created moment doesn’t: Back in New York, two years later, we eavesdrop on Ned’s therapy session as he broods over whether he should stop talking about “the family romance.” For all its musicality and visual inventiveness, Schutt’s description of the shrink’s response (“Of course not! Like a stern housekeeper, knock, knock, knocking an iron against a shirt, banged against and scorching the shirt, never once looking up at Ned, Dr. K said, ‘Of course not!’”) fails to focus and elucidate the character’s perceptions, but instead diffuses them, thus falling prey to charges often levied at poetic imagery in prose—too writerly, too precious.

Neither Ned nor Isabel can find traction in their lives: She takes in a blind, sickly shih tzu while he moons over Phoebe, an old girlfriend; both possess refined sensibilities (evidenced liberally by their dialogue: Isabel asks Ned about the weather outside and he replies, “Milky sunshine”) and want to be artists while lacking the will to decide what to do. Life after London is a drag—Isabel tutors high schoolers while Ned frets over his agent’s advice to turn his new batch of stories into a more salable memoir. Into their sodden lives comes Clive, who allows himself to be seduced by Isabel almost out of habit. It’s hard to know just why she falls for him; her strong distaste for sex (he “guided her downward to disappointment: Why did it always end like this with that musty part in her mouth?”) remains unchanged. Still, unlike Isabel and her husband, Clive is anything but diffident: When he hails a cab he does so with a “large, showy whistle,” and the vehicle stops “with accompanying verve.” This may be reason enough for her to agree to stay at his house in Maine so he can paint her, even though Dinah (a tolerant wife in the Continental mode) will be there, along with the less indulgent Ned.

No idyll, this summer retreat puts the two couples in close proximity, a Pinter-like setup that Schutt exploits with metaphoric flourish. After all four meet for the first time at a local fish joint, Ned and Isabel square off:

“What’s the matter now?” Isabel asks. Common as a kitchen cut, her question starts a fight.

“Did I blow it?” Ned asks.

“What do you care? You were in no hurry to be liked.”

“Please,” Ned says. “I wasn’t entirely uncharming was I?”

“No. You were very flattering about Clive’s hair.”

Clive and Dinah carry on peaceably; she has always had a plan with the older, powerful men in her life—“Simply subdue them by loving them more.” The dovetail fit of her self-sacrifice and Clive’s self-assurance makes for invidious comparison with the Bournes, who offer each other little more than sour intellection and paralysis. Ned’s healing gesture toward Isabel at the guesthouse, suggesting they “read the Odyssey together,” is comically wan, especially when so neatly paired with the scene in the next paragraph, in which Clive comes upon his wife crying on the lawn as a storm approaches. Why, he asks, and she replies, “Any number of reasons.” He nudges her toward the house, up the stairs, with the pledge, “I’ll squeeze it out of you, whatever it is.” “Yearning was all very fine,” Clive tells his daughter, “but only the doing counted.”

Schutt may treat Fitzgeraldian themes of marriage, money, and thwarted affection (Isabel even quotes Nick Carraway’s famous line about being “both enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life”), yet her style is stately, more Jamesian, although her elliptical tack is James on a severe diet. This concision and its consequent rhythm—the narrator’s perceptions and the characters’ thoughts register in quick bursts of sharply struck notes—excite us; in their brevity and elevated pitch, her sentences sound ready to pounce upon intimate disclosure. Like James, Schutt penetrates to the core energies of human drama with a pointillist’s touch; feeling is lent graceful shape, less readily apprehensible, but ultimately more incisive. The poetic devices, however, can sometimes prove more compelling than the discovered content. But such instances only throw into relief the overall risk Schutt takes. Prosperous Friends presses adventurously against mere telling’s quotidian restrictions and attempts to enact “the lyrical impulses of the soul.”

Albert Mobilio is an editor of Bookforum, and his most recent book is Touch Wood (Black Square, 2011).