When I was in Chile in the summer of 2001 I stupidly asked a taxi driver, in my bad Spanish, if Pinochet were dead.

“No,” he said, and by the way he looked over his shoulder I could see the question made him nervous. “No, he is still alive.” He showed me the National Stadium as we drove through Santiago on our way to Valparaiso and said, “Pinochet’s prison.” For a moment I thought he meant Pinochet was imprisoned there. Then I remembered how the stadium had once been used, during Pinochet’s viciously oppressive rule (1973–90): as a huge detention center where suspected political dissidents were held and in many cases “disappeared.”

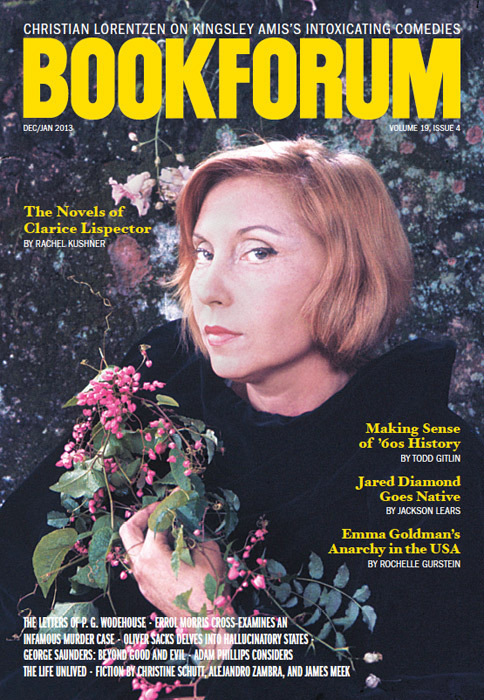

Toward the end of Alejandro Zambra’s astonishing new novel, Ways of Going Home, a thirtysomething character, too young to have directly suffered Pinochet’s atrocities, says of the National Stadium: “The largest detention center in 1973 was always, for me, no more than a soccer field. My first memories of it are happy, sportive ones. I’m sure that I ate my first ice cream in the stadium’s stands.”

This is a sentence, mind you, written by a Chilean to other Chileans: It’s a shocking and honest thing to say. No doubt many other Chileans of Zambra’s generation—he was born in 1975—also had a first ice-cream cone in that notorious stadium. That said, Zambra is not naive, and his characters—children and adults alike—as a rule despise Pinochet. In an early scene, set in the mid-’80s, a nine-year-old (and never named) narrator regrets that an earthquake has knocked down his favorite wall at school, a wall that all the kids scribbled on: “I thought about all those messages smashed to smithereens. . . . One phrase I found especially funny: Pinochet sucks dick.”

I was a fan of Zambra’s Bonsai when it came out in the US in 2008, and I recommend it enthusiastically, but Ways of Going Home elevates him to the status of living writers we “simply must read,” like Denis Johnson, Lydia Davis, and Mary Gaitskill. His voice is as natural and intimate as Roberto Bolaño’s, an obvious but healthy influence, and his subjects—love, memory, death, and guilt—are as big as he can find.

The book’s narrative structure is ambitious too. Ways of Going Home is divided into four parts: “Secondary Characters,” “Literature of the Parents,” “Literature of the Children,” and “We’re All Right.” The first and the third parts present themselves as sections of a novel in which a narrator recalls events he experienced in Santiago in 1986, when he was nine. In parts two and four, an adult author (he is thirty years old in 2006) describes his life and efforts to write the book that is presented in the first and third sections. In other words, it is a book about a book within a book, and the sections are narrated by two people (or perhaps two versions of the same person): the young “fictional” kid and the adult who has written him. It sounds confusing and postmodern in an annoying way, but on the page it makes sense, and is an illustration of precisely the storytelling we do to reconcile ourselves with the past—especially when there are so many conflicting perspectives on that past.

Ways of Going Home confronts a fundamentally political problem, particularly how to engage with the false version of events presented by a dictatorship. That said, Zambra does not try to rewrite the Chilean legacy of the brutal Pinochet years. He knows—he simply and directly shows—the complex morality of his material. “School changed a lot when democracy returned,” the adult narrator remembers. “I had just turned thirteen and was belatedly starting to get to know my classmates: children of murdered, tortured, disappeared parents. Children of murderers, as well. Rich kids, poor kids, good kids, bad kids. Good rich kids, bad rich kids, good poor kids, bad poor kids.” Given this context, it is difficult to approach the past without endangering the future. Late in the book the narrator’s love interest admits, “I don’t feel guilty. But I feel that lack of guilt as if it were guilt.” For the narrator of the novel—as, again, one expects is the case for Zambra’s contemporaries—there is an upsetting but understandable blend of indignation, shame, and near apathy. How does it feel to be the son or daughter of a politically sanctioned murderer? Of a politically sanctioned victim of murder?

Zambra uses his narrators—child and adult—to haunting effect. Even in the chapters narrated by the nine-year-old, he never adopts a kid’s narrative tone; rather, the child’s perspective—characterized by confusion and lack of experience—is relayed in an adult’s voice. There is the sense that the child is being controlled, if not by a dictator, then by an awareness greater than his own. The effect can be haunting. The book opens: “Once, I got lost. I was six or seven. I got distracted, and all of a sudden I couldn’t see my parents anymore.” It’s 1985—the year Santiago suffered the Algarrobo earthquake—and as ordinary adult Chileans are disappearing into prison, the children (like “secondary characters”) can do nothing more than stand by and watch.

But Zambra is too sly to leave it at that, and he often uses the kid’s limited understanding of grave situations to achieve high dramatic irony. During the earthquake, for example, the narrator tries to sneak into a girls’ tent (because of the earthquake, everyone has moved outdoors), “but the policeman’s daughter threw me out, saying I wanted to rape them.” He continues: “Back then I didn’t know what a rapist was but I still promised I didn’t want to rape them. . . and she laughed mockingly and replied that that was what rapists always said.” This is a tricky exchange, and it displays how nimbly Zambra can evoke scenes that are threatening and innocent at the same time. The girl’s logic is typical of secret police: Whatever you say further confirms your guilt, especially a denial of guilt. But it’s also playful, even hilarious: We have a nine-year-old who doesn’t understand what rape is, protesting to a bunch of same-aged girls that he’s not a rapist, just so he can stay up and play with them and their dolls.

The novel is on one level a love story, cunningly woven into the self-deceptive psychology of the Pinochet years. The child narrator is asked by his first love, the slightly older Claudia, to spy on a mysterious neighbor, Raul. Our hero takes the job eagerly: He’s bored, and he wants to impress the girl. We gather that Claudia is in love with Raul and is jealously having him watched for that reason. We don’t realize until later that this man is not, as it first appears, having a series of homosexual liaisons; rather, he is hiding men who have been marked for imprisonment. He is a fighter for the resistance, one of the few moral exemplars in the novel.

Like Bolaño, Zambra has a magical, conspiratorial tone, and we feel like a friend is telling us a very personal story. “This wasn’t invented, it really happened,” Zambra writes, and he’s convincing. Again like Bolaño, Zambra makes you proud to be a reader: The narrator discusses Madame Bovary (even though he doesn’t quite understand it) and quotes Tim O’Brien, Romain Gary, and Natalia Ginzburg. Books are a large part of what makes the narrator’s world—“To read is to cover one’s face. And to write is to show it,” he tells us, after he’s become a writer. His hero lives through books. Reading, Zambra reassures us, is a political act, a way of reassembling one’s sense of home, of history and its malleability, following a disaster.

Of course, returning home is a messy process. Thomas Wolfe gets it half-right when he writes, in You Can’t Go Home Again: “You can’t go back home to your family, back home to your childhood . . . back home to the old forms and systems of things which once seemed everlasting but which are changing all the time—back home to the escapes of Time and Memory.” The truth is that everyone has to go home, but in the process of returning, we always change what that home originally was. Memory adds, subtracts, distorts. As does writing fiction. In the last section of the novel, “We’re All Right,” the novelist who has told us the whole story doubts the value of his own book, and spends his time deleting, rewriting, cutting, changing it from first person to third person, writing verse.

After democracy is restored in Chile, and his parents’ financial circumstances improve, we are not surprised when the narrator’s father puts up a new bookshelf, stocks it with a mixed bag of books—Allende, Grisham, Verne—and explains (to his discomfited, literary son): “Thanks to that library, your mother has started reading and I have too, though of course I’d rather watch movies.” As usual, Zambra can’t resist the joke: Reading and writing are crucial to the restoration of Chile, but the books aren’t all good ones. The parents, we suspect, are too close to Pinochet’s horrors to confront them. It is the children who have the distance to try to recover and accept.

That distance is part of what allows Zambra’s adult narrator to become a writer. “I left home fifteen years ago, but I still feel a kind of strange pulse when I enter this room that used to be mine and is now a kind of storage room. At the back there’s a shelf full of DVDs and photo albums jumbled in the corner next to my books, the books I’ve published. It strikes me as beautiful that they’re here, next to the family mementos.” His books are incorporated into his memories of his family, and into his reconciliation with his history. This young man’s books don’t pretend to change what happened. Rather, they do something even more powerful: They show how an author can use fiction in an attempt to reconstruct a home where he can live now.

Clancy Martin is the author of the novel How to Sell (2009) and the forthcoming nonfiction book Love, Lies and Marriage (both Farrar, Straus & Giroux).