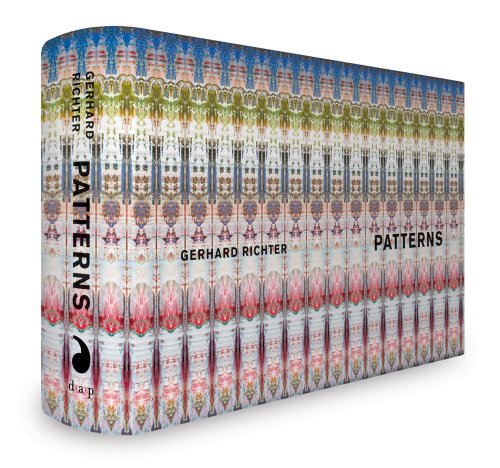

IN A RECENT TIME magazine profile, the renowned German artist Gerhard Richter confessed his admiration for John Cage, particularly the composer’s famous dictum on poetry, “I have nothing to say and I’m saying it.” Cage substituted silence for actual notes, and Richter, in recent works of epic reproduction, substitutes multiplication for brushstrokes. Nowhere is this more in evidence than the artist’s book Patterns, a dizzyingly intense exploration of one of his works, 1990’s Abstract Painting (724-4). Richter digitally divided an image of that artwork a dozen times (then split those divisions in 2, then 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256, and so on) to produce 4,096 increasingly thinner strips of the slash-and-splatter original oil painting, each magnified to the size of the original. Richter then mirrored each slice to create a total of 8,190 images. While only presenting a selection of these, this book is still ample testament to Richter’s rigorous focus and totalizing sensibility, one that’s yielded many such encyclopedic projects—for instance, 2007’s 4900 Colours, an assemblage of 196 panels based on color charts that can be rearranged in eleven variations. The effect of diving into this book—and that is precisely how it feels, like plummeting headlong through an image—recalls the 1977 Charles and Ray Eames documentary Powers of Ten. In that film, the camera zoomed exponentially far out in space to view a picnic scene from one hundred million light years away and then zoomed back in, through the solar system, the earth’s atmosphere, and then into a man’s hand, and his DNA, stopping on an image of a single, shimmering proton. Patterns affords travel in both directions, too; if treated like a flip book, you can page from the front or the back, macro to micro, or vice versa. As fragments of the image are subject to greater and greater enlargement, they become increasingly elemental—the intricate geometries of the earliest magnifications, evocative of Islamic art and Persian rugs, give way to more regularized motifs, the colors striating into glowing bands that conjure the works of Gene Davis. Each division reveals another nuance about the constituent parts of color and shape. Pausing to study any one spread (an image mirrored across the book’s gutter) can be just as vertiginous and rewarding: The intricate beauty feels at once machined and biomorphic. Allow yourself to fall into any one image: Relax your eyes for a minute. No 3-D picture of the Starship Enterprise will emerge. But you will see something at least as surprising: what division and multiplication actually look like, the very shape and motion of arithmetic. In this depiction of the invisible, Richter assuredly links abstract painting to the abstraction of numbers.