[[img]]

Five years ago, anticipating the birth of my first child, I went to the hospital (my wife came along, incidentally) with only one book tucked into the suitcase: P. G. Wodehouse’s Lord Emsworth and Others (hereafter L.E.A.O.). Its very title suggested grab-baggery, lighter-than-light reading—just another in the line of ninety-odd books of fiction that the British author wrote between his 1902 debut and his death in 1975. I can’t remember a word, only that there were golf stories, some tales from the Drones Club, and that it closes with an exploit or two of the mercenary Ukridge, arguably my favorite Wodehouse character. All I really recall is that L.E.A.O. served as the perfect prose pacifier for a particularly frazzling Life Episode.

Far be it from me to dissuade the more steely-minded from packing Serious Literature—what Bertie Wooster would term an “improving book”—for the birthing room, tomes in which the stakes are high, the narratives opaque or vertiginous, the revelations life-changing. My life was going to change; I needed something casual on that cold December day, a book that wouldn’t upset my fragile mental state: entertainment without conflict, verbal dexterity solely in the service of comic relief. What I am saying is that hospitals would do well to stock L.E.A.O. in the gift shop, next to the “It’s a Boy!” balloons.

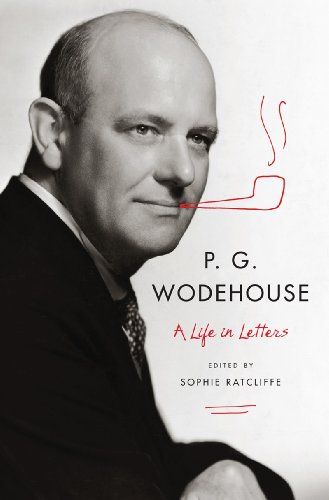

It’s easy to think of Wodehouse (1881–1975) as the purveyor of literary comfort food. The flyleaves of Overlook Press’s Collector’s Wodehouse editions would make excellent wallpaper for a sanatorium, and simply seeing the spines on a shelf never fails to soothe me. A friend mentions that any random Wodehouse is his go-to subway reading—perfect for dipping into, no emotional commitment, it doesn’t matter if you don’t finish it. Indeed, you might have already finished it: The remarkable consistency and volume of his output means you can be pretty far into something before it dawns on you that you’ve read it before. Even his titles are designed to blur the lines. I couldn’t be trusted to tell you the difference between Mulliner Nights and Mr. Mulliner Speaking, Heavy Weather and Summer Lightning, Carry On, Jeeves and Very Good, Jeeves, though I’ve read them all. (I think.) This is in fact a virtue of Wodehouse’s work, although as we learn in a new collection of his letters, the author was sensitive to accusations that he was continually raking over the same fictional ground. In 1932, Wodehouse grumbled about a review by J. B. Priestley, who “called attention to the thing I try to hush up,—viz., that I have only got one plot and produce it once a year with variations.”

Meticulous plotting was central to the Wodehouse method, and before writing each of his books he would work out its convolutions on a staggering scale. “I have done a twenty thousand word scenario of a new novel, and shall be starting it soon,” he wrote to his friend Denis Mackail, a novelist, in 1931. “I find that if one has the energy to make a long scenario, it makes the actual writing much easier.” More than four decades later, he told the Paris Review, “Before I start a book I’ve usually got four hundred pages of notes. Most of them are almost incoherent. But there’s always a moment when you feel you’ve got a novel started. You can more or less see how it’s going to work out. After that it’s just a question of detail.”

How interesting, then, to read what a younger Wodehouse wrote to a friend in 1914: “That is what I’ve always wanted to be able to do, to interest the reader for about five thousand words without having any real story. At present, I have to have an author-proof plot, or I’m no good.” Voice is subservient to narrative. Of course, an author as long-lived as Wodehouse will change his views on craft and ambition over the years. But in that contradiction between form and style—in a pinch, predestination and free will—lies a curious truth. Could it be that for us readers (after all, the most important part of this equation), Wodehouse in the end achieved his goal of dispensing with “any real story”? “It’s just a question of detail,” Wodehouse remarks about the composition, after the heavy lifting is done. Perhaps the aspects of his books that give us the most pleasure—the utter insouciance, the similes of fizzy genius (comparing, to pluck at random from the sacred oeuvre, a dour countenance to a “V-shaped depression off the coast of Iceland”)—could only be arrived at once the scaffolding was absolutely secure. Which is to say, a reader with much on his mind about the uncertainties of life might well have deeper reasons for immersing himself in a story called “There’s Always Golf.”

• • •

Both the Priestley gripe and the wish for plotlessness surface in P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters, best read as a formidable supplement to Robert McCrum’s 2004 Wodehouse: A Life. In telling contrast to the certainties of plot that he generated, and the languorous existence of many of his beloved characters, Wodehouse himself had to carve his own way in the world, and the charmed part of his life was not simply the fruit of his talent. Though the biographical interludes by the book’s editor, Sophie Ratcliffe, will be unwieldy for those familiar with McCrum, A Life in Letters gives us the grit along with the wit, including the grubbing and venting that get left out of most readers’ mental portrait of the man. His early letters to his friend Eric George are dialect-drunk proclamations: “I consider the splendid burst of triumphant joy in the last line [of George’s poem] without a par (or ma) in the English langwidge!” His later missives can be caustic. “One would have thought that anyone reading the book would have gathered that Gally was a dapper elderly man,” he fumes about the cover art for Galahad at Blandings (1964), “and this son of unmarried parents has made him look twenty-five and one of the Beatles at that.”

Wodehouse was a star pupil at Dulwich College, the public school where he boarded while his father worked in Hong Kong (and where, just a few years later, Raymond Chandler was educated). There he burned with dreams of fame, signing a poem “P. G. Wodehouse-Shakespeare.” But he did not go off to Oxford as anticipated, ostensibly due to his family’s financial vagaries. Though this stung, he later said that he never would have succeeded as a writer had he gone to college. It was true: Now he had a chip on his shoulder, and something to prove. “I am going into the Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank,” he wrote to George after receiving the news that higher education was shut to him. “For two yrs I will be in England from the time I am 19. So I will have 2 yrs to establish myself on a pinnacle of fame as a writer.” Writing in 1921 to his beloved daughter, Leonora, he gives a droll sketch of one of his older brothers:

Jolly old Armine writes from India hinting that he is tired of his job before he has started it, and rather thinks of branching out on his own as an advertising specialist—or, presumably, anything else that requires no work. One of the things that buoys me up when I am toiling away on these hot afternoons is the thought that I am putting by money for Armine to touch me for later on. I wonder when he will next have the hateful task of asking me for a thousand quid to buy a collar-stud.

Armine had gone to Oxford, where he was a gifted student and poet—but it’s Wodehouse who makes a name for himself.

Wodehouse is surely the greatest writer to have been employed by HSBC. While at the bank, he led a sort of double life: freelancing, calling in sick whenever he had a chance to fill in at a newspaper where a friend worked. He soon ditched the job, working as a columnist and publishing his first books; he became an early transatlanticist, visiting New York in 1910 and eventually spending most of his life in America.

In 1914, with fifty dollars in his pocket, he married Ethel Wayman, a widow, at a small church on East Twenty-Ninth Street—a happy union that would last until his death. (Many years later he would write: “Another anniversary! Isn’t it wonderful to think that we have been married for 59 years and still love each other as much as ever except when I spill my tobacco on the floor, which I’ll never do again!”) He adopted and adored her daughter, Leonora, whom he typically addressed as “Darling Snorky.” An admirer of W. S. Gilbert, Wodehouse found fame on Broadway as a lyricist, teaming up with Guy Bolton and Jerome Kern. “I shall have five plays running in New York in the Autumn, possibly six,” he reported in 1918. With Bolton and Cole Porter, he worked on Anything Goes; tooling a revival in 1961, he came up with a “masterly couplet” that captured the spirit while bringing it gently up to date:

When the courts decide, as they did latterly,

We could read Lady Chatterley

If we chose,

Anything goes.

The success of his books made Hollywood take notice, but after moving there in 1929, he was woefully underused; the most memorable scene in the Wodehouse-scripted A Damsel in Distress is Fred Astaire’s kinetic, multi-limb, dialogue-less drum solo. A graver muteness was to come. In 1940, while living in Le Touquet in France, Wodehouse, age fifty-eight, was taken prisoner by the Germans and interned at Tost in Poland. Aside from the separation from Ethel, camp life was not hard. Wodehouse finished most of the Jeeves novel he was working on (Joy in the Morning) and remained generally stiff-upper-lipped, but made a mistake that was to haunt him for decades. A political innocent (e.g., from an April 1939 letter: “I don’t think Germany would dare do anything that would bring England and France down on them”), Wodehouse agreed in 1941 to make some radio broadcasts in Berlin—humorous accounts of camp life. The content was innocuous, but the context was horrendous, and he found himself branded a traitor by some in England. George Orwell, Evelyn Waugh, and others defended him, but the taint lingered. Though he cooperated with his biographer Richard Usborne in the ’50s, he not only insisted on bowdlerizing the “Internee” section, but in fact “destroyed all that broadcasts material . . . to prevent Usborne selling the stuff as an article to some magazine.” The writer whose books unfold in a timeless world, its language blissfully at play in a zone without referents, is also the sort of writer to become a pawn of history and its harsh realities.

• • •

In his correspondence, Wodehouse expressed annoyance at Tom Jones and was “bored stiff” by Jane Austen; he found Fitzgerald’s stories overrated (“AWFUL . . . Frightful!”), and couldn’t be counted a fan of the letters of Henry James. I will probably never read Shelley’s “The Revolt of Islam,” after Wodehouse’s description of the experience as “like being beaten over the head with a sandbag.” “Have you noticed how everybody is writing like Hemmingway [sic] nowadays?” he grumbled in 1931. “It seems to me a darned easy way of writing,—just short, breathless sentences.” (L.E.A.O. has a story called “Farewell to Legs.”) “By the way, do you ever find that you have spells of loathing all poetry and thinking all poets, including Shakespeare, affected fools?” he asked Mackail in 1951. “I am passing through one now.”

Of twentieth-century writers, he liked the work of Agatha Christie, Anthony Powell, and Waugh, all of whom he corresponded with. Perhaps more surprisingly, he enjoyed George Herriman’s Krazy Kat strip, Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead (though he found it “filthy”), Lawrence Durrell, and The Dick Van Dyke Show. And, if we are to believe his letters to his lifelong friend William (“Bill”) Townend, the works of William Townend.

Just as Wodehouse’s most famous creation, Jeeves the omniscient valet, initially had the smallest of bit parts in an otherwise forgotten character’s story, Townend (humorously dubbed “Villiam” or “V. T.”) first appears fleetingly, in Wodehouse’s impassioned letters to their fellow Dulwichian Eric George. Townend turned down a scholarship to Cambridge to become an artist. Wodehouse encouraged him to try his hand at writing, which he did with respectable productivity but to scant notice. “I often brood on your position as a writer as compared with what it ought to be,” Wodehouse wrote in 1949. “I can’t see, for instance, why Conrad is looked on as a sort of magician while you don’t get reviewed. And I believe it’s because you have never sought publicity in any form.” Astonishingly, by this point in time, Townend had written “thirty-odd books.”

Wodehouse disingenuously puts his friend’s obscurity down to the fact that Townend has “never mixed with the literary gang.” Today, the one Townend title that is known, if at all, is Performing Flea, a “Self-Portrait in Letters by P. G. Wodehouse, With an Introduction and Additional Notes by W. Townend” (1953). The book, they hoped, would present Wodehouse in a softer light after the divisive Berlin broadcasts, as well as boost Townend’s literary stature. There is a vertiginous moment in A Life in Letters when we read Wodehouse discussing how to not simply edit but rewrite their correspondence for publication. “The great thing, as I see it, is not to feel ourselves confined to the actual letters. I mean, nobody knows what was actually in the letters, so we can fake it as much as we like.” (Regarding a similar project involving his showbiz comrade Guy Bolton, Wodehouse wrote: “I think we shall have to let truth go to the wall if it interferes with entertainment. . . . WE MUST BE FUNNY!!!!!!”)

Townend lives on because Wodehouse lives on. Love Among the Chickens (1909), Wodehouse’s seventh book, introduces his first great comic (anti)hero, Ukridge, who derives partly from stories that Townend related of an actual acquaintance, Carrington Craxton. Throughout A Life in Letters, Wodehouse asks Townend for help with plot and character. “For Heaven’s sake rally to the old flag & lend a hand with the plot,” he wrote in 1908, while composing a pseudonymous serial. Twenty-four years later, putting together a Jeeves and Wooster confection, he was still sending out the call: “Now, one other S.O.S., if you have time.”

“I haven’t developed mentally at all since my last year at school,” Wodehouse confessed to Townend in 1933, at the age of fifty-two. “All my ideas and ideals are the same.” When Wodehouse got his agent, Paul Reynolds, to take on a Townend story, he wrote, “He is an awfully good chap, and I would rather see him land in some big market than sell my next serial for forty thousand. We were at school together and have been friends since 1897. I feel sort of responsible for him, as I egged him on to be a writer. He used to be an artist before that.”

Two of Wodehouse’s novels have “Bill” in the title, and he might have had his pal in mind when suggesting to Leonora that she name his grandchild—if a boy—William instead of Edward: “Then we should have a good honest Bill, which would be great.” Most affecting is the song “Bill,” from 1918’s Oh, Lady! Lady!! (and later Show Boat), in which Wodehouse’s lyric extols the ordinariness of the titular man, with a beautiful pause in the penultimate line:

And I can’t explain

It’s surely not his brain

That makes me thrill

I love him because he’s—I don’t know—

Because he’s just my Bill.

Townend’s letters, like those of Wodehouse’s other correspondents, do not appear in this book, but Bill emerges as one of its domineering presences—a secret sharer and a glimpse of what Wodehouse might have become had he met with failure instead of success. Whether the best-selling novelist actually needed his friend’s advice, or even esteemed his novels (he characterized them as “gloomy studies” to Reynolds), is beside the point. Wodehouse regularly gave money to his less prosperous friend. In 1933 he wrote, “My idea is to guarantee an overdraft, so that you will feel safe. If you don’t need it, then it’s still there. But if you want to take six months off to write a novel, that will be at the back of you.” He attached terse postscripts, knowing that his wife might read letters from Townend and disapprove of the financial support: “Well cheerio. Don’t refer to any of this in your next letter.”

For a novelist, writing letters is writing that is not writing: “What a lot there is about Pekes and football!” Wodehouse bemoaned to Townend while prepping their correspondence for publication. But a collection of letters is the unconscious narrative the author generates over the years. The complexity of Wodehouse’s long relationship with Townend is more poignant than anything in his fiction—a mix of loyalty, guilt, and generosity that is most moving when it approaches the invisible: “Don’t mention the enclosure when you write.” In this way, P. G. Wodehouse: A Life in Letters is like nothing Wodehouse published in his lifetime, though the sentences are all his, as are the spaces between the lines.

Ed Park is the author of the novel Personal Days (Random House, 2008) and the literary editor at Amazon Publishing. He is working on a new book of fiction.