One dark night in South Vietnam in mid-1969, I stopped for a beer at the rickety shack that served as an officers’ club for the First Marine Division, based a few miles outside of Da Nang, on the central coast. I had just delivered an intelligence report warning of an enemy rocket attack on the city.

I found myself sitting next to a guy with a war-weary, thousand-yard stare. He turned out to be a navy doctor assigned to one of those medical teams that (along with other “hearts and minds” civic projects) were supposed to bring the locals over to our side. He started telling me about days spent taking peasants’ blood pressures, cleaning sores, listening to tubercular chests, giving shots, and so forth. And then I noticed his cheeks were moist with tears. He took a drag on his cigarette.

“We fix ’em up,” he said softly, wiping the tears away, “and then they”—he nodded at the distant sound of outgoing artillery—“then they blow ’em away.”

It was called “H & I fire,” short for “harassment and interdiction”: willy-nilly artillery barrages into the dark night to terrorize Communist units in the area. The problem was that people—civilian people—lived in those “free fire zones,” too. By night, the doctor told me, the marine gunners vaporized the very people he’d spent the day “helping.”

In truth, you only needed a few weeks in Vietnam to know the place was seriously fucked up. A few more weeks in, you just wanted to survive the madness. “Mistakes were made,” it was always said—and it still is, in many quarters—about the conduct of the war: The civilian slaughter wasn’t deliberate, it was just horribly careless or crazed, people said. A tragedy. Even events as macabre as My Lai—where perhaps five hundred unarmed people, almost all of them old men, women, and children, were gunned down by US Army troops over several hours—were “understandable,” the apologia went, given the nature of a war that pushed GIs beyond the breaking point.

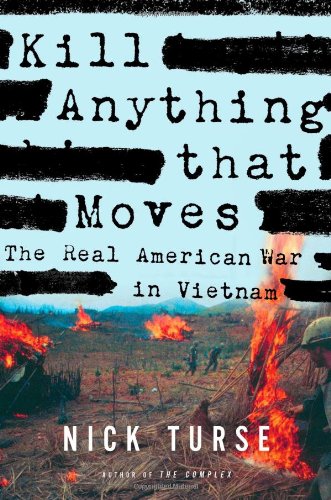

Nick Turse is here to tell you—to show you—that’s wrong. My Lai was not a mistake or an aberration or even an exaggerated case of aggravated assault, he persuasively demonstrates in this grim but astounding book: It was born of a deliberate body-count strategy that came down from on high and was pursued energetically by colonels down to sergeants. It was a strategy that logically led to an approved practice on the ground that’s summed up in the book’s title: “Kill anything that moves.”

Of course, this is hardly the first time allegations of mass murder in Vietnam have been raised. Following Seymour Hersh’s groundbreaking My Lai exposé in 1969, a flood of influential long-form magazine pieces and books appeared that “ate away at the notion,” Turse writes, “that each atrocity brought to the attention of the American public was a singular incident.”

And then, suddenly, the flood turned into a trickle, and the trickle to dust. War crimes had become “so commonplace as to be barely worth mentioning or looking into,” Turse writes, adding that “it was almost as if America’s leading media outlets had gone straight from ignoring atrocities to treating them as old news.” An atrocity now had to be something bigger than My Lai to write up; otherwise, editors told reporters, it would seem like piling on.

There was something bigger, actually, Turse recounts: a six-month-long spree of mass murder, rape, and pillaging in the Mekong Delta, carried out by soldiers of the Ninth Infantry Division, under the command of General Julian Ewell, that was swept under the rug.

Thoroughly reported out and documented by Newsweek’s Saigon bureau chief, Kevin Buckley, and his Vietnamese-speaking reporter Alex Shimkin, the five-thousand-word blockbuster was buried by the magazine’s editors for several months, at which point Buckley asked permission to sell the piece elsewhere but was turned down. Only in June 1972 did a gutted, 1,800-word version of Buckley’s account of the 1969 rampage see print, stripped of eyewitness interviews and even Ewell’s name. “In its eviscerated state,” Turse writes, “the article attracted only a slight ripple of interest.”

Years later, Newsweek editor Kermit Lansner, a former Art News editor who “socialized with the Long Island painters of the Abstract Expressionist movement,” according to his 2000 New York Times obituary, explained to Buckley why he had buried the piece. “He told me,” Buckley says in Turse’s book, “that it would be a gratuitous attack on the [Nixon] administration at this point to do another story on civilian deaths after the press had given the army and Washington such a hard time over My Lai.”

Yes, Nixon was treated so unfairly. The president did his part in keeping the lid screwed on, naturally. In 1969, when the prosecution of top Green Beret officers for the unauthorized execution of a suspected North Vietnamese double agent threatened to unmask the CIA’s Phoenix assassination program, Nixon intervened to have the case quashed. (The men, whose plight was highly publicized, came home as heroes.)

Following the black eye it got over My Lai, the military, too, was making it harder to get allegations of war crimes to surface or stick. In Turse’s detailed accounting, witnesses were ignored or told to shut up, files went missing, prosecutors declined to prosecute, and cases were dropped. Even more troubling, those who reported instances of murder, rape, arson, and pillaging by their erstwhile brothers-in-arms did so at the risk of their lives. Nobody was going to jail, least of all high-ranking officers who had abetted the killing.

By 1973, a cloak of silence had settled over what really happened in Vietnam. Forty years later, Turse aims to set the record straight.

But what is it a record of? Were the atrocities peculiarly American, as some on the left have posited, or the predictable by-product of any war, especially a counterinsurgency campaign in which the guerrillas, their civilian supporters, and the truly innocent are virtually inseparable?

After reading Turse’s meticulous, extraordinary, and oddly moving account, it’s hard to avoid concluding that the US record in Vietnam has more in common with the Wehrmacht and the Imperial Japanese Army than “the greatest generation” that fought those enemies in World War II.

Of course, we Americans recoil from such comparisons. But here’s the rub: Substitute Vietnam’s “gooks,” “dinks,” and “slopes” for World War II’s Jews, Gypsies, and gays, add in more than a million civilian casualties from air strikes, napalm, Agent Orange, and mass murder beyond My Lai, and what have you got? Industrial-style killing on a massive scale.

It didn’t start out that way, of course; it never does. First came a more benign-sounding idea, the “body count,” the theory that you could measure progress in Vietnam principally by the number of “enemy” killed, not territory gained and held. The numbers crunching was enthusiastically grasped by Defense Secretary Robert F. McNamara, a former Harvard Business School and Ford Motor Company whiz who, Turse writes, “had designed statistical methods of analysis for the War Department during World War II, most famously systemizing the flight patterns and improving the efficiency of the bombers that decimated German and Japanese cities.”

In South Vietnam, this vision of “technowar,” as the sociologist James William Gibson dubbed it, was quickly adopted by General William Westmoreland, the US commander, under the tactical rubric “Search-and-Destroy.”

“The pressure to produce high body counts flowed from the Pentagon to Westmoreland’s Saigon villa, down the chain of command, and out to the American patrols in the Vietnamese countryside,” Turse writes.

The problem was that the enemy was hard to find. The Viet Cong doctrine was to shoot and run, and then blend into the civilian population. The GIs’ frustration, along with casualties from booby traps and a demand for higher body counts, seeded cyclones of murder in hamlets all over South Vietnam.

Far from discouraging such mayhem, senior officials encouraged it, Turse found, based on his extensive interviews with former soldiers, court testimony, and after-action reports. High body counts led to promotions and time off.

Entire units were sometimes pitted against each other in body count competitions with prizes at stake. This helped make the body count mind-set even more pervasive, lending death totals the air of sports statistics. “Box scores” came to be displayed all over Vietnam—on charts and chalkboards (also known as “kill boards”) at military bases, printed up in military publications, and painted as crosshatched “kills” on the sides of helicopters, to name just a few of the most conspicuous examples.

The huge kill count, though, rarely matched the paltry number of weapons found. Something was terribly wrong.

Turse, managing editor of the Nation Institute’s TomDispatch.com, has traveled to some of Vietnam’s remotest hamlets (most with modest little memorials to their lost loved ones), as well as to many settlements along America’s back roads, to find people with sorrowful new stories to tell.

Among the veterans and peasants, there is one constant. As one former marine put it, “We was going to kill anything that we see and anything that moved.”

Someone should have been held accountable. It was never to be. But willful forgetting, burying the facts and reinventing the Vietnam experience in a more heroic light, has exacted a heavy cost on us—not to mention on Iraq and Afghanistan—Turse argues.

“Never having come to grips with what our country actually did during the war, we see its ghost arise anew with every successive military intervention,” he says. “Was Iraq the new Vietnam? Or was that Afghanistan? Do we see ‘light at the end of the tunnel’? Are we winning ‘hearts and minds’? Is ‘counterinsurgency’ working? Are we applying the lessons of Vietnam?”

And finally: “What are those lessons, anyway?”

Jeff Stein, a former military-intelligence case officer in Vietnam, is the author of A Murder in Wartime:The Untold Spy Story That Changed the Course of the Vietnam War (St. Martin’s Press, 1992).