For years it’s been said in circles both polite and impolite, and in ways both delicate and indelicate, that America’s blacks should learn to live more like America’s Jews. Writing in the Jewish Journal in 2006, the black former New York Times reporter Eric Copage said he once asked himself “if there were things Jews do that blacks should adopt to become more prosperous.” “My answer,” he continued, “an emphatic yes.”

Unpacking what it means to “act Jewish” is certainly a task to which entire volumes—to say nothing of countless Woody Allen bits—have been devoted. But in general, when people say that blacks need to act more Jewish, one gets the sense that what they’re saying is that blacks need to adopt a sense of clannishness and dogged self-reliance. American blacks and Jews share a history of oppression and—at least up to the creation of Israel—a certain statelessness. But the Jewish community has, broadly speaking, folded into itself in a way that many black Americans, some of whom fought and died to integrate with white America, have not. To wit, in a July 2012 obituary for former Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, Times of Israel writer Matti Friedman fondly recalled Shamir’s utter lack of faith in everyone but other Jews. “Jews, he believed, could rely only on themselves,” writes Friedman, “and especially on their ability and willingness to use force in their own defense.”

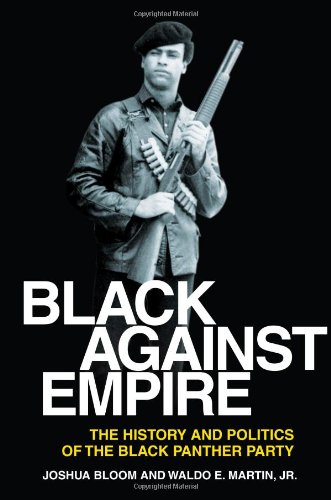

If there is one reason for us to read Waldo E. Martin Jr. and Joshua Bloom’s new book, Black Against Empire—and there is a good deal more than one reason—it should be this: The book reminds us of how close we came to a world in which America’s blacks were, in fact, acting like the Jews. In the 1960s and ’70s, the Black Panthers tried very hard to build a nation in which black people were sectarian, autonomous, and prosperous in much the same way Jewish communities throughout the United States had been for decades. And for their efforts, the Panthers were sabotaged, prosecuted, and murdered.

The communal and idealistic vision of nationalist self-help that shaped the Black Panther movement has largely vanished down the national memory hole—in all likelihood, because few quality recollections of the movement exist. Dramatic treatments of the Black Panther story have so far yielded a lackluster 1995 biopic, Panther, and a better but little-seen one-man play, A Huey P. Newton Story, which was later adapted into a small film by Spike Lee. Books, though abundant, have been similarly disappointing. Former Panthers themselves have contributed some of the chronicles, and in those cases the works typically falter because of their authors’ biased perspectives on a subject already rife with several, if not dozens of, different interpretations. Others were incomplete in their coverage.

Black Against Empire sets itself apart from its predecessors with its sheer thoroughness. The pursuit of completism is difficult enough in most fields of research, but Black Panther completism is a particularly Byzantine beast. Not only are the various narrative appraisals of the Panthers’ short but influential career partial and self-interested, but many of the basic facts about the movement also have been buried beneath clandestine police operations that likely will never afford later historical researchers a full and accurate view. That kind of obfuscation, note Bloom and Martin, has sometimes led to the maligning of the Panthers as nothing more than an “organized street gang,” as leftist-turned-neoconservative writer David Horowitz called them in the early 1990s—and has obsessively reiterated ever since.

“While many of the criminal allegations that Horowitz and his colleagues made about Huey Newton and other Panther leaders were thinly supported and almost none were verified in court,” write Bloom and Martin in their introduction, “these treatments also omit and obscure the thousands of people who dedicated their lives to the Panther revolution, their reasons for doing so, and the political dynamics of their participation, their actions, and the consequences.”

Bloom and Martin sallied forth despite the thorny terrain. And, with testimony from former Panthers, archival Panther literature—the authors say they’ve amassed the only “near-complete” collection of the Black Panther newspaper—past academic texts, and declassified FBI and police documents, they’ve pieced together an account that should be called, above everything else, “definitive.” Beginning with the childhoods of Newton and his Panthers cofounder, Bobby Seale, the book omits very little in its explanation of how the two men went from being the poor sons of manual laborers to Bay Area college students to globally respected militants atop the premier black revolutionary group in America.

To be sure, this completeness can be exhausting at times—as when the authors find it necessary to do things like arbitrarily describe people’s outfits at semi-important events, or tell you insignificant details like “In the heat of the sun and the enthusiasm of the crowd, Newton began to sweat.” In those moments, it feels as if the point isn’t so much to let the reader in on an important morsel of knowledge as it is to remind the reader of just how much homework Bloom and Martin have done: They’ve dug so deep, you see, that they can tell you the exact moment beads of perspiration began to form on a now-dead man’s brow.

Readers should go in to Black Against Empire expecting a lot of that sort of fatty, stunted prose, but they should indeed go in—with one caveat: They will be much happier if they approach the book more as a narrative reference text than as a flowing piece of historical nonfiction.

With this in mind, Black Against Empire, even for those generally familiar with the Black Panther legacy, can be an engaging study of the outer limits of Panther knowledge. What’s more, the book’s honest attempt to understand the intricacies of the movement is underscored by its commitment to nonpartisanship: While Bloom and Martin take great care not to vilify the Panthers as armed thugs, neither do they romanticize them simply as a misunderstood civil rights group. The result is a downright scientific analysis of a subject that leaves most readers understandably unable to stay neutral.

If there’s any clear villain in Black Against Empire, it’s the United States government. Martin and Bloom never let movement leaders such as Newton, Seale, and Eldridge Cleaver off the hook for their litany of hubristic and tactical faults, some of which ultimately doomed the organization—but the authors also insist plainly that the Panthers’ troubles were greatly augmented by the underhanded meddling of police and FBI agents. Spearheaded by then-director of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover, the agency’s cointelpro operations waged a campaign of destruction that targeted not only the Black Panther Party’s armed resistance to police authority, but also the group’s most benign and productive elements.

At the height of what Bloom and Martin call the movement’s “impressive array of community programs,” the Panthers were responsible for the following socialist-minded services, which varied from local chapter to local chapter: the Free Breakfast for Children Program, liberation schools, free health clinics, the Free Food Distribution Program, the Free Clothing Program, child-development centers, the Free Shoe Program, free busing to help the destitute visit jailed relatives, the Sickle Cell Anemia Research Foundation, free housing cooperatives, the Free Pest Control Program, the Free Plumbing and Maintenance Program, renters’ assistance, legal aid, the Seniors’ Escorts Program, and the Free Ambulance Program.

In response to the Panthers’ community-enrichment efforts—which also fed, clothed, and assisted white people in need—Hoover was furious. He wrote a letter to one of his special agents in San Francisco in 1969 asserting that the Free Breakfast for Children Program “was formed by the BPP for obvious reasons, including their efforts to create an image of civility, assume community control of Negroes, and to fill adolescent children with their insidious poison.”

Though most people envision the late ’60s when they think of the Black Panthers, the party didn’t shutter its last office until 1982. But by then, the closure was something of a formality: Newton and Seale’s idealistic vision had long since succumbed to notoriously bitter infighting, a changed political landscape, and relentless FBI attacks—several of which claimed the lives of key party leaders. Huey Newton would become addicted to drugs and was murdered in the Oakland streets in 1989. And later, Eldridge Cleaver died a converted Mormon Republican who scoffed at some of his earlier political beliefs.

As they survey the grim close of the story, Bloom and Martin call upon the cultural Marxism of Antonio Gramsci—something of a well-worn trope in academic studies of leftist politics. But as I came to the end, my mind wandered instead to the recent presidential election, in which Mitt Romney lost, then proceeded to blame his defeat on his African-American opponent’s abundant offer of “gifts” (read: welfare) to blacks, Latinos, and other subjugated groups. It’s almost certainly too much to hope that Romney would pick up a copy of Black Against Empire and learn the sobering truth that, not so long ago, a significant cadre of blacks exhibited the kind of sweeping independence he and many of his Republican colleagues claim they’d like to see. These insurgents fed themselves, clothed themselves, schooled themselves, reared their own children, and provided medical care to their own communities, and with little to no help from the government. And what did the leading federal body charged with Panther oversight call this self-reliance? “Insidious poison.” Because, you see, it’s not true black self-reliance unless it’s carried out on terms approved by the white government.

Cord Jefferson is a writer and editor in Los Angeles.