Charles Jackson barely ever wrote a piece of fiction. The vast majority of his output—five novels or collections in the decade beginning 1944, and one final novel fourteen years later (“99 percent of this novel is lubricious trash,” read the Kirkus review)—was thinly disguised fact. His first, and by far his best-known, work was The Lost Weekend; it was essentially his homosexual alcoholic’s diary artfully made fiction. It made headlines for its depiction of alcoholism; the homosexual component got far less attention, likely because of the distorted Freudian fever gripping the nation, in which alcoholism and homosexuality (or “latent homosexuality”) were considered similar and interlocking manifestations of immaturity. After that one success, desperate for more attention and more money, Jackson coughed up lurid stories as often as he could write or dictate them. Most of them failed, because the fiction was too unbelievable, despite its accuracy—or else it was too poorly executed.

In retrospect, though, it’s hard not to think he was simply ahead of his time. Jackson would have been the most cherished writer of the 1970s or ’80s. He could have been in the vanguard of the era when that script was flipped, when we started publishing glossy first-person fiction as fact.

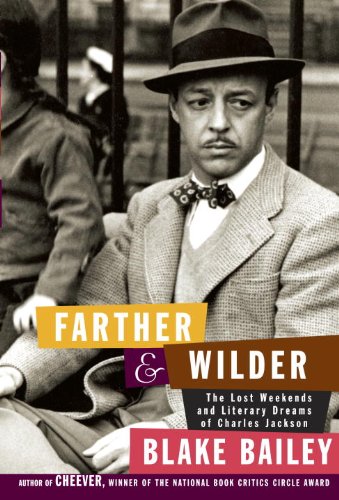

An insanely stuffed biography, Blake Bailey’s Farther & Wilder: The Lost Weekends and Literary Dreams of Charles Jackson (Knopf, $30) identifies just how much of Jackson’s work was drawn from life—and just how ugly it all was on the inside. Bailey’s comprehensiveness of research is harrowing, and the few remaining unknowns about Jackson clearly torture him. Most of Jackson’s life was spent promising a blockbuster and a masterpiece to friends and publishers alike. (“I feel confident that the book will come to be recognized instantly as an American classic,” he grandiosely wrote of what became his second book, The Fall of Valor [1946], which has since been reconsidered as both a pioneering gay book and a radical and offensive work of homophobia, but in either case not an American classic.) He circulated his unfinished manuscripts for comment far and near, he lied about his advances and income, he stuffed his homes with signed celebrity head shots, he name-dropped ludicrously. He was everything that would come into full flourish in the ’90s.

He became a self-elected spokesman for alcoholics as well, a role that would become commonplace among our current (but at least currently well-paid!) tortured confessional homosexual writers. As is true in almost all such celebrity cases, Jackson’s career as a recovery booster didn’t go well. While Alcoholics Anonymous was flying Jackson around the country to make speeches, he was often in the grips of a crippling Seconal addiction or “only drinking beer.” If only he’d been here now! Out of every greater relapse he could have sold a new magazine story or a new installment in his grand multivolume gritty memoir, ever in progress.

As a study in career frustration, Jackson’s life story is fully instructive as well. He came in hot with a few stories, selling two to Dwight Macdonald at the Partisan Review in 1939. Jackson labored in the mills of radio soap-opera serials for $200 a week in 1942 (that’s $2,817.10 in 2012 dollars). He was nearly forty. The Lost Weekend was published in 1944. It was a crushing success, and made into a classic Billy Wilder movie, which won the best-picture Oscar for 1945. Jackson went briefly to Hollywood; he bought a huge house in New Hampshire. He was published once in the New Yorker and then rejected regularly for decades. (Whether that was because his stories were terrible or because of the famous prudishness of the magazine is unclear.) In his early years, he was supported most often by Bronson Winthrop, in his later years, by Roger Straus. By 1955, he was the script editor of Kraft Television Theatre, produced by an ad agency, at $500 a week ($4,283.47 in today’s money). But by the next year, Kraft wanted more viewers; pressed to become more topical and ever less offensive, the show became Kraft Mystery Theatre and then expired. Jackson himself wouldn’t expire until 1968, when he achieved his last successful overdose in the Chelsea Hotel, but he would teach an “evening extension class at the women’s college” at Rutgers around 1964. He lived out most of his adult life overspending, broke, compromising, and borrowing money; at the end, he was kept by a devoted, simple fellow.

In those later years, he’d left his hideously long-suffering wife and children and was palling around with a fairly trashy downtown and/or homosexual crowd: “Arthur C. Clarke . . . remembered how [Peter Arthurs]”—the author of what Kirkus called a “lurid, pathetic, dankly repetitious account” of his relationship with Brendan Behan—“had introduced him to Jackson, Arthur Miller, and Norman Mailer.” This brief fun was all too little and too late. Like so many writers, Jackson desperately wanted regard and acclaim. He was alternately too busy making cheesy money or too busy drinking himself into the hospital—although, to his credit, his number of hospitalizations would shame any of our tepid little tipplers. Each era monetizes the scandals that the general public most admires. Being years out of step seems a terrible loss, if only for the publishers and agents.

Choire Sicha is the author of the forthcoming Very Recent History (Harper, 2013).