It’s been forty years since John Ford passed away, but filmmakers continue to wrestle with his legacy. The directors of three recent Oscar contenders—Django Unchained, Lincoln, and Zero Dark Thirty—are a case in point. Quentin Tarantino, accused of gross insensitivity by Spike Lee in portraying slavery as material for a spaghetti western, deflected Lee’s charge by damning Ford’s westerns (still the genre standard) as true racism. “Forget about faceless Indians he killed like zombies,” said Tarantino. “It really is people like that that kept alive this idea of Anglo-Saxon humanity compared to everybody else’s humanity.” Django Unchained’s direct Oscar competition, both critically and aesthetically, was Steven Spielberg’s reverential slave-era drama Lincoln (and, one suspects, the real target of Tarantino’s comments). Of any living director, Spielberg is Ford’s most vocal admirer and emulator, dutifully taking up Ford’s apparent mission to document our entire, imperfect national experience. Zero Dark Thirty? To defend Kathryn Bigelow’s depiction of Americans cruelly, ruthlessly in pursuit of an enemy, critic J. Hoberman invoked the cruel, ruthless Indian fighter of Ford’s greatest film. “As with John Wayne in The Searchers, Maya’s mission is personal,” he wrote in The Guardian. “Is she condemned, like Ethan Edwards at the end of The Searchers, to ‘wander forever between the winds’?”

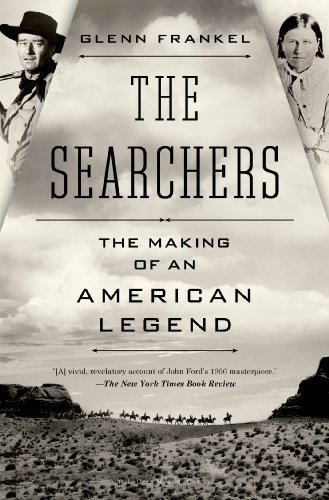

Glenn Frankel’s important new book, The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend, grapples with all these questions in exploring the Indian war and its aftermath as they furnished the backdrop for Ford’s signature film. Frankel comes to the task uniquely qualified. While at the Washington Post, he won a Pulitzer for reporting on Israel and Palestine, which affords him a solid grounding in parsing the issues raised by this film. “Like the Plains Indian Wars, this, too, was an intimate war of populations in which women and children were both victims and participants,” Frankel writes of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, “in which only one could triumph and the loser must be exterminated physically or culturally or both.”

Indeed, Frankel devotes two-thirds of his book to the history upon which The Searchers is based—beginning with the abduction of nine-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker during the 1836 Comanche massacre of her family. Her uncle James Parker—a dishonest, widely disliked Baptist clergyman and devout Indian hater—spent eight years searching for her. He hired gunmen, indiscriminately killed and tortured Indians, terrorized villages with a militia—yet never found Cynthia. In 1860, the US Cavalry recaptured her during the massacre of her Comanche tribe. Then a wife of a chief and mother of three, Cynthia was returned with her daughter to her white relatives—torn a second time from her family—never to see her two sons again. An embarrassment to her white family (she loved her Comanche husband and children and wanted to return to them), she lived out her years a lonely, sad woman until her death in 1871.

Frankel approaches The Searchers much as Greil Marcus analyzed Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes in The Old, Weird America (2011), rooting out the distant folk origins of the popular art we think we know. The Searchers shares such a history, not unlike the murder ballads that professed to chronicle the exploits of Stagger Lee or Mack the Knife. Cynthia’s life inspired journalism, political careers for her white rescuers and her descendants, a prairie opera, folklore, and, eventually, Alan LeMay’s 1954 novel, The Searchers.

Frankel interprets the 1956 movie as not only 120 years of fermented myth but a true creative collaboration that fused LeMay’s novel, aging western star John Wayne, and Ford’s vision of frontier mythology. Ford had already tried to adapt Cynthia’s story. But it was in LeMay’s unique focus on James Parker—white warrior, moral failure, heartbroken uncle, vengeful racist, and archetypal cowboy on a mission to save a girl—that Ford saw the basis for his movie and Wayne’s greatest role. The saga of Parker’s quest brought together Wayne’s increasingly violent screen persona and Ford’s growing ambivalence toward the settlement of the American West, and they converged in Monument Valley, Arizona, where much of the film was shot. Ford and his colleagues renamed Parker “Ethan Edwards,” then pushed the character’s rougher edges further. When he learns his niece is the wife of a Comanche, her rescue turns into a family honor killing of a white woman Ethan Edwards sees as defiled. Is The Searchers racist, or does it depict racism? “The Searchers is one of the most resonant of all American films,” Stanley Crouch insightfully observed. “The evolution of the tale shows the West with its mask pulled off, acknowledging the parallel savagery of the whites and the Indians, slaughters of the innocent abounding on either side.”

One can quibble with some features of Frankel’s account. He glosses over Ford’s complicated political life. He has odd ideas about filmmaking. Of Ford’s spartan shooting style—on set, he shot only what he imagined the final cut to be, and from no additional angles, in order to keep his film safe from studio recutting—Frankel tells us, with not a little cowboy swagger, “Over-shooting was an insurance policy for the weak willed and supercautious.” Ford’s highly controlled methods also left him with a number of stiff mediocrities, whereas Chaplin, Hawks, Coppola, and Ashby certainly benefited from looser conceptions of their final cuts while filming.

Nevertheless, Frankel’s book is a necessary and overdue addition to film history. He frees The Searchers from the best-of list makers and director idolaters who only see it in the context of more movies. Frankel reconnects The Searchers to the tragic culture from which it sprang—and thereby reminds us of the reason it haunts us still.

Ben Schwartz is an Emmy-nominated writer and the comics editor of the Los Angeles Review of Books.