After living in China for more than a decade, what struck Peter Hessler most upon returning to the US was the way Americans talk. The Chinese “aren’t natural storytellers—they are often deeply modest, and they dislike being at the center of attention.” The Chinese conversational style suits Hessler, whose trademark reporting method could be dubbed Extreme Patience: When he finds a new place, he likes to settle in for what most people would consider an unreasonably long time. At one point in Strange Stones, Hessler’s meticulous, deep-dive collection of essays from China and beyond, he refers offhandedly to the “three years” he spent visiting the Chinese factory town of Lishui. In “Dr. Don,” his masterful profile of a small-town Colorado pharmacist, he cites “different conversations that spanned more than a year.”

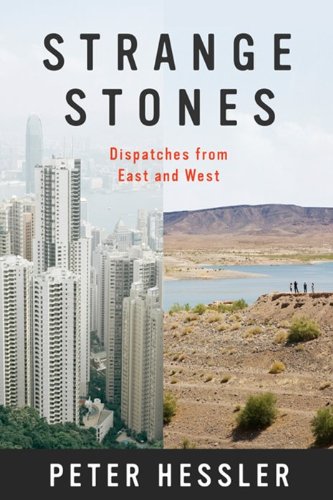

For a journalist who can seem so settled, Hessler gets around. The pieces that make up Strange Stones jump from a rat restaurant in Guangdong to an auto manufacturing plant in Anhui to the Tokyo underworld to a village in Nepal before landing in rural Colorado, where Hessler recently moved with his wife, journalist Leslie Chang. While the pivots can feel jarring, these articles, which originally appeared in the New Yorker between 2000 and 2012, hang together like tracks on a well-done mixtape. What they lack in narrative thrust they make up for in thematic refrains: In “Underwater,” a small town on the Yangtze confronts its impermanence as it prepares to be swallowed by the Three Gorges Dam; in “Walking the Wall,” Hessler documents how the Great Wall has survived for centuries while its history and meaning shift with the political winds. Stories of uprooting—“Boomtown Girl” follows one of Hessler’s former students as she encounters the mixed fortunes of factory life in Shenzhen—stand alongside tales of homecoming, including Hessler’s own in “Go West.” Other essays, like “Home and Away,” in which Hessler trails Yao Ming through China and the US after his rookie season with the Houston Rockets, count as both.

The strongest pieces in Strange Stones read not as snapshots so much as time-lapse films. “Hutong Karma,” a portrait of an ancient Beijing alleyway undergoing renovation, at first feels like a collection of loosely related scenes: Hessler sells some junk to a local Beijing recycler (his book manuscript goes for fifteen cents); an ad hoc men’s club forms around a fancy new toilet facility in the run-up to the Olympics; he takes a final tour of an old friend’s apartment before it gets demolished. The result is less a storyline than a meditation on change and how Beijingers cope with it. Hessler notes how one particular hutong structure has gone from Manchu royal compound to office of Chiang Kai-shek to Communist Party digs to Yugoslavian Embassy to, finally, the Friendship Guest House. “That was hutong karma—sites passed through countless incarnations, and always the mighty were laid low.”

Hessler takes the long view on human events, like the proverbial Chinese farmer who refuses to grieve when his horse runs away, or to rejoice when it returns. The title Strange Stones refers to Chinese rocks, some natural, some carved, that look like other things—a head of cabbage, a rhinoceros. Hessler’s subjects share that quality: Look once, and the rise of the Yangtze is an ecological and humanitarian disaster. Look again, and it doesn’t seem so bad compared with the political and economic tragedies many adults across China have lived through. A new McDonald’s at first strikes Hessler as an affront to his traditional Chinese neighborhood, until he discovers how privacy-starved couples treat it as a cozy date spot. At the root of all this is Hessler’s own shifting baseline. Moving back to the US after living abroad, he acknowledges, “China became my frame of reference; I tended to think of the United States mostly in contrast to what I knew in Asia.”

“Chinese Barbizon,” about an art factory town in Zhejiang, best captures the bizarro wormhole that connects his two homes. In the galleries of the Ancient Weir Art Village, Chinese artists paint pictures to be sold on the foreign market, particularly scenes of Venice and, inexplicably, Park City, Utah. One artist, Chen, has no personal attachment to her work, nor can she identify the landmarks she paints. Scenes are instead labeled according to a code: “HF-3127 was the Eiffel Tower. HF-3087 was a clipper ship on stormy seas.” In the nearby industrial town of Lishui, Hessler interviews a young man whose English consists mainly of the names of the chemical dyes necessary to produce the right color of brassiere clasp: “Sellanyl Yellow,” “Padocid Violet,” “Padomide Rhodamine,” etc. These moments are funny, but just as the reader is starting to feel smug, Hessler cuts to Park City, the subject of those Chinese oil paintings. The mayor turns out to have a soft spot for China. He even keeps a copy of Chairman Mao’s “Little Red Book” on his shelf, from which he has gleaned a bit of wisdom: “‘Serve the people,’ he said, when I asked what he had learned from Mao. ‘You have an obligation to serve the people.’”

In other words, the way the Chinese see America isn’t that different from the way Americans see China. We take what we need—be it the names of dye chemicals or a trite political slogan—and ignore the rest. What unites us isn’t that we’re all the same, but that we’re all similarly focused on the immediate. Occasionally the distant becomes immediate—the American car industry explodes in China; Chinese telemarketers target a family in middle-of-nowhere Colorado—and that’s where Hessler shines. The last line of the book, spoken by Dr. Don as he looks up at the Colorado stars, sounds like an argument for the unity of things: “‘When you see them from here, they look so close together,’ he says. ‘It’s hard to believe they’re millions of miles apart.’” Hessler’s writing achieves a similar effect, not by conflating East and West but by making the threads that connect them more visible.

Christopher Beam is a writer living in Beijing.