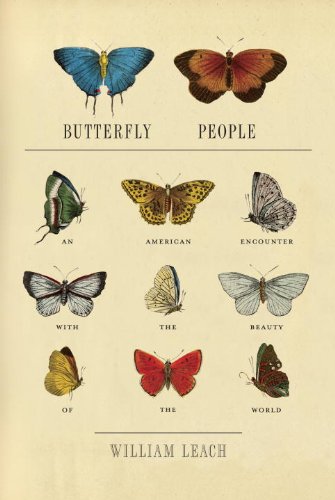

When a Paris Review interviewer asked Vladimir Nabokov what he liked to do best besides writing novels, the author replied, “Oh, hunting butterflies, of course, and studying them. The pleasures and rewards of literary inspiration are nothing beside the rapture of discovering a new organ under the microscope or an undescribed species on a mountainside in Iran or Peru.”

Nabokov was far from alone in this passion. The particular rapture of butterfly collection and study, the sensuous delight of this most painterly branch of entomology, was commonly voiced by its nineteenth-century adherents, as historian William Leach notes in his new book, Butterfly People. “On taking it out of my net and opening the glorious wings my heart began to beat violently,” recalled the English naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace about spotting a rare Malaysian butterfly in 1859. “The blood rushed to my head, and I felt more like fainting than I have done when in apprehension of death.” But inherent in the thrill of nineteenth-century butterfly collecting was an acquisitive drive that would eventually poison the collectors’ passion at its source, leaving us, at the other end of the long and destructive twentieth century, with a lot of pinned bugs under glass.

Leach tells this ultimately tragic story through several exemplary biographies selected from among the prominent American entomologists, collectors, and explorers of the late nineteenth century. The best known is William Henry Edwards, great-grandson of the Calvinist preacher Jonathan Edwards. For Leach, the younger Edwards represents many of the contradictions of nineteenth-century naturalism. He was, along with his contemporary and fellow entomologist Samuel Scudder, a great observer and cataloguer of butterflies, one who did as much as any American to further the world’s understanding of the insect’s life cycle. Scudder and Edwards’s volumes on the butterflies of North America were works of literary elegance and aesthetic beauty. Their debates over Darwinist classification were at the heart of American scientific culture in their time. But Edwards supported his intellectual labors with an income derived from coal mining in West Virginia. He began blasting at the land he owned on the Kanawha River in 1880, when virgin forest still covered more than 90 percent of the state. By 1900, all those trees were gone, thanks to the new barons of coal, lumber, and the railroads. Edwards never seemed to be aware of his partial responsibility for the death of West Virginia’s forests, where he spent so much time chasing some of his favorite butterfly species.

If Edwards had not had his coal mine, his career might have looked a bit more like that of butterfly hunter Will Doherty, a fascinating and more marginal figure who becomes, through Leach’s affectionate telling, a victim of butterfly collecting’s more blatantly capitalistic charms. Doherty began his career as an aspiring lepidopterist, but detoured into the more lucrative profession of butterfly collecting in the wake of a family crisis. Still, collecting afforded him only a tenuous livelihood. Journeying through the distant realms of the British Empire and beyond with his nets, traps, and bait, assisted by teams of natives, dreaming in vain of a wife who had “conceived a romantic affection for me upon reading my articles on the Lycaenidae and the Hesperiidae,” contracting every variety of tropical illness, he was chivied along by the villain of Leach’s book, William Holland, the director of the Carnegie Museum of Pittsburgh and a frequent client. “[The] trouble with you my dear Doherty,” wrote this tightfisted and venal collector, “is that you are not definite and business-like in your dealings with us.” In his efforts to please Holland, Doherty traveled hundreds of miles through East Africa by train to get his specimens mailed off, fended off a lion with only a butterfly net, and, finally, contracted scurvy and dysentery, from which he died in 1901, at the age of forty-four.

Holland is not the only example of a collector gone wild in Butterfly People. A more complicated and far more sympathetic figure in the same genus is the German-American stone carver and butterfly addict Herman Strecker, who held the largest private collection of butterflies in American history. Strecker began collecting butterflies when he was five years old. Poorly educated, not much engaged by stone carving (he specialized in marble angels for the graves of children), socially inept, and unlucky in love, Strecker channeled all his life’s energies into his collection. He began collecting at firsthand, in the woods near Reading, Pennsylvania, where he lived, and then broadened his reach through a widening network of sources throughout the country and then around the world. After a full day in the marble shop, Strecker would retreat to his butterfly rooms and his “things of endless joy,” as he called his dead insects. “Were it not for the butterflies, [life] would have been indeed almost ‘one drear night long’ but the delight to be found in the study of nature compensates for the many miseries,” he wrote a friend in 1872. His collection, containing more than fifty thousand specimens, is now in the Field Museum in Chicago.

Leach observes that Strecker’s purity of purpose would have no place in the more “utilitarian,” economically focused science of the 1890s and early 1900s. The new entomologists worked for farmers; their job was to kill insects, not to glory in their beauty, and they viewed amateur enthusiasts as romantic relics. From a modern standpoint, the loss is inestimable. The vivid, intimate connection with nature that the butterfly people cultivated and celebrated in the course of their scientific study is now almost forgotten—and along with its extinction, we have not merely lost the habitats and species detailed with such care a hundred years ago, but also some essential part of humanity. Leach’s book is a brilliant work of history, but it’s also a compelling lament for a lost way of existing in the world.

Britt Peterson is a writer in Washington, DC.