In 1942, the literary quarterly Accent accepted James Farl Powers’s short story “He Don’t Plant Cotton,” his first published fiction. Powers was working then for a wholesale book company in Chicago, having dropped out of Northwestern because he couldn’t afford tuition. He wrote his editor that he hoped to quit his job, to “get away and, yes, you guessed it, Write.”

By the time Accent published his second story—the classic “Lions, Harts, Leaping Does,” an astonishing achievement for a twenty-five-year-old author—Powers was behind bars. Having fallen in with a group of Catholic pacifists, he was sentenced to three years in a Minnesota penitentiary after failing to appear for induction into the army. (Catholics weren’t eligible for conscientious-objector status.) Powers accepted this development with a good-natured fatalism that seems as ingrained a characteristic as his moral stubbornness. “There is justice, hardly poetic,” he wrote to his sister and her husband, “in the way I find myself tied up in destiny with millions of people when what I want most is to be separated from them.” Like many lovers of humanity, he didn’t always like run-of-the-mill humans that much, and being surrounded by them was his main complaint about prison. As his release approached, he looked forward to “not waking up in the morning in the midst of a multitude.” He was still hoping to get away and Write.

It wasn’t to be. Paroled after thirteen months, Powers was assigned grueling work as a hospital orderly until the end of the war. “I have letters from editors wanting things, and I can’t get time to produce them,” he wrote to a friend. “I’m becoming a has-been without ever having really been.” He was twenty-eight years old.

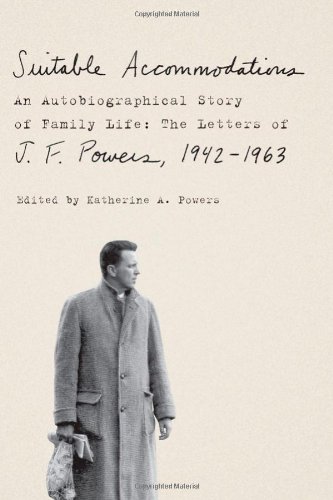

The feeling that circumstances conspired to keep him unproductive stayed with Powers throughout his life. Shortly after leaving the hospital, he married Betty Wahl, a fellow fiction writer he met after one of her teachers asked him to read Betty’s novel. Supporting their children—eventually five in all—and making a home in various cities in the Midwest and in Ireland would replace imprisonment and forced labor as the obstacles to his art. Throughout these years, Powers “planned to write a novel about ‘family life,’” his daughter Katherine Anne writes in her introduction to Suitable Accommodations:

It was to be, in some fashion, the story of a writer, an artist, with bright prospects, a taste for the good things in life, and an expectation of camaraderie as he made his way in the world. The man falls in love, gets married, has numerous children—but has neither money nor home. . . . The novel would be called Flesh, a word infused with Jansenist distaste, conveying the bleak comedy and terrible bathos of high aesthetic and spiritual aspiration in hopeless contact with human needs and material necessity.

Powers never wrote this novel. “Or so it seemed,” his daughter adds. “Jim was, in fact, not only living it but creating and embellishing it in his correspondence, a body of writing whose size and extent go some way toward explaining the small number of his published books.” As this volume’s ungainly subtitle suggests, Katherine Anne has selected and edited her father’s letters with the aim of completing this unwritten novel, a kind of Irish-American House for Mr. Biswas.

In her introduction, her afterword, and various editorial notes throughout, she tells the story of a writer manqué, spending his days on trifles, preparing to begin the life’s work that will make his name. He is fated never to be ready, but there is an ironic redemption awaiting: The very trifles on which his days were wasted were the life’s work, hiding in plain sight. But there is an obvious problem with applying that familiar story to this case: J. F. Powers was no writer manqué. In the two decades covered by this book, he wrote his first two story collections and most of the stories that would make up his third. These stories, published in the New Yorker and elsewhere, gained him a well-deserved reputation as one of the finest writers of his generation. He also wrote the first of his two novels, Morte D’Urban, winner of the National Book Award in 1963. Three and a half books in twenty years might not seem like a lot, but the work was written to last, and it has: Half a century on it is all in print. It’s true that Powers worked slowly, and that he didn’t produce as much as he or his admirers would have liked. It’s also true that he never wrote the novel of family life he occasionally mentions in these letters. But that is mostly because he’d found early on the subject that would occupy both of his novels and most of his short fiction: the daily life of the Catholic clergy in the Midwest.

Nowadays his material might seem hopelessly irrelevant. But Powers’s priests—neither the benign authorities of yesterday’s imagination nor the monstrous predators of today’s—retain their ability to surprise. They are men who set out on what they believe to be the most important task in the world—shepherding souls—but invariably find themselves caught up in petty squabbles, fund-raising, and administrative intrigue. In a typical early story, “The Forks,” an idealistic young curate is taken to task for giving his galoshes to a freezing man on a picket line during the Depression. Later in the story, a widow approaches the younger priest. She wants to know what to do with the money her husband has left her, and she understands priests are good with such matters. When he suggests giving it to the poor, she reacts with disgust: She was looking for investment advice. Powers was first and foremost a comic writer, and the comedy survives even if the crowded parish life he describes no longer exists. And his comedy has an edge, because Powers believed, as his priests occasionally remember to believe, that the stakes in their line of work were as high as they could be. In fact, the story Powers tells again and again is precisely that of “spiritual aspiration in hopeless contact with human needs.”

A collection such as Suitable Accommodations is usually an opportunity to celebrate a writer’s work, particularly when that work is not as widely appreciated as it ought to be. On this basis alone, it’s unfortunate that Katherine Anne Powers chose to frame this volume as the great book her father never wrote, instead of as a companion to the great books he did write. Worse, the conceit seems to have begotten other unfortunate editorial decisions. The volume ends midway through Powers’s life—just as he receives the National Book Award and the widest recognition he would ever have—because, KAP writes, “the novel Jim might have written concludes here.”

His relationship with other writers is largely absent. Katherine Anne Porter was such an enthusiastic advocate of Powers that he gave her name to KAP. But only a handful of his letters to Porter, one of his chief rivals as the best short-story writer of the time, are included, all concerning unrest in his family situation. There are more letters to Robert Lowell, whom Powers met at Yaddo and remained friends with throughout his life, but again they are narrowly focused on domestic matters. A recent volume of Saul Bellow’s letters included several from this time period to Powers, whom Bellow considered one of his finest contemporaries, but none of Powers’s letters to Bellow are here, perhaps because Powers did not complain in them about his duties as a husband and father, or about money. “I have cut letters and passages that are not necessary to the story,” KAP writes in a note, “including a large number concerning JFP’s deliberations and negotiations with editors and publishers.” Such deliberations are just the sort of thing one hopes to find in the letters of a major author, but they suggest a writer who was publishing consistently, and so they are an inconvenience here.

None of this means that Suitable Accommodations isn’t worth reading, particularly for those who already know Powers’s work. Illuminating bits slip through almost in spite of themselves. “Fr. George writes of the nice lady parishioner who came to see him about her soul and, more immediately, her finances,” Powers tells his sister. “She wanted him to recommend a good investment.” (There is no editorial mention of the use he would make of this story in “The Forks,” nor is his response to Father George Garrelts included.) Powers’s typical humor and style are on display throughout. The volume’s title comes from his remark that “we are pilgrims only, but since the trip’s quite long, I tend to look around for suitable accommodations.” (Though again there is no editorial mention that he would repurpose the phrase for his story “The Devil Was the Joker.”) About a priest from whom he has been advised to ask for work he writes, “He expects to get to heaven for not having made any impractical moves during his stay on earth.”

Powers certainly didn’t intend to get to heaven that way. “I hate regular hours,” he wrote to Betty Wahl before their marriage, in what might seem a kind of warning. “I like to walk when I want to. Sleep when I want to. Listen to music. I will go pretty far to get in a position to do these things.” The victims of this willfulness were, of course, his wife and children, and one can well understand why KAP bluntly writes, “Growing up in this family is not something I would care to do again.” But from the outside there appears something noble about this lifelong fight against practicality, particularly given the work it produced.

And Powers knew this work deserved to last, even if he usually expressed the knowledge with self-protective irony. (“I feel pretty sure it’s immortal,” he writes about Morte D’Urban, “just how immortal is the question.”) It may be, as his daughter suggests, that Powers saw himself as a failure for not having written more, but his failure was of a particular sort. Listening to his hopeful young curate, the pastor-protagonist of Powers’s second novel, Wheat That Springeth Green, thinks, “The trouble was . . . that Bill’s understanding of the Cross, like that of most young people today, was nominal, narrow, unapocalyptic, and so failure to him didn’t, as it did to Joe, make much sense.” Powers knew that every decent writer, like every decent priest, is destined to fail—because he works in a fallen world and aims for the impossible. Such knowledge might not make failure any less agonizing to live through, but it makes the failure make sense.

Christopher Beha is a deputy editor of Harper’s Magazine.