The more nonfiction you read, and from further back in time, the harder it gets to pronounce the word “new” in New Journalism with a straight face. I’m thinking partly here of pieces like Ned Ward’s “Trip to Jamaica,” 1698—Edward Ward, seminal Grub Street hack, writing sarcastically and in a detail-studded first-person prose, a reportorial style that pointed forward to Defoe while listening to Bunyan, about an actual trip he’d made to Jamaica with other prospective settlers. Sixteen ninety-eight—that’s early. When Ward published his dispatch, London’s printers were just emerging from under the so-called Licensing Act, which for half a century had restricted them to a limited range of material. Parliament let the act expire, or “lapse,” in 1695, sparking the Grub Street explosion of magazines and newspapers that helps mark the dawn of the eighteenth century. Modern English-language journalism begins New, and never really looks back.

Even if we were not to feel like going back so far, though, and wanted to stay merely with, say, the earlier twentieth century, there too lies a host of forgotten antecedents, foremost among them the experiments carried out by editor-magnate Henry Luce at Fortune magazine in the 1930s. Luce hired a bunch of poets and freelance literary-intellectual types to write ostensible economic journalism for him. Dwight Macdonald, Daniel Bell, Archibald MacLeish. The last did truly remarkable pieces for Luce. Fortune sent MacLeish to write about an automobile assembly plant. A pie factory. One of MacLeish’s finest pieces involved an imaginative but fantastically well-reported reconstruction of the last day in the life of Ivar Kreuger, a former titan of industry turned bankrupt and suicide. “The stair smelled as it had always smelled,” MacLeish began, “of hemp and people and politeness—of the decent bourgeois dust.” These are pieces Joseph Mitchell would have had in his head when he started at the New Yorker in 1938. They did as much, in the way of seeing how far journalistic forms could be bent toward essentially narrative or essayistic ends, as any of the ballyhooed first-person magazine pieces of the 1950s and ’60s.

Among the writers Luce hired in the mid-’30s was an unknown young man, a recent Harvard graduate from Tennessee named James Agee, who wrote poems (a collection he’d half completed as an undergraduate was nominated, by MacLeish, for the Yale Younger Poets prize in 1934, and won). Jim Agee: tall, darkly handsome. Prematurely melancholy in a manner both pretentious seeming and deeply real. A great talker, a great (which is to say, bad) drinker, an expert at accentuating or cloaking his southern roots, as occasion demanded. Possessed of as much talent—if by “talent” we mean sheer wattage of verbal combination—as anyone in his generation, a talent that he was on his way either to wasting, if you hold with his latter-day detractors, or to fulfilling, in some necessarily fractured way. The magazine sent him all over the country to be literary on a range of vaguely money-related topics. He wrote about commercial orchids and blasting powder, strawberries and cockfights.

In 1936, at the age of twenty-seven, he got a more ambitious assignment. He would travel south, to west-central Alabama, in the company of a photographer he knew, but not well, and whose work he admired—a slightly older man named Walker Evans, star of the newly dubbed “documentary school,” a midwesterner but already an experienced hand at taking pictures of poor southerners (for the Farm Security Administration). Their joint task was to do a piece on tenant farmers; white sharecroppers—except that they weren’t really sharecroppers. Sharecroppers work someone else’s land for the privilege of keeping part of the crop. Tenant farmers are merely renting the land, in order to grow their own crops, and cattle and pigs—all of which, the idea goes, will make them enough money to pay off the landowner and keep some profit. The cruelty that made this distinction little more than a cynical joke is that only in bumper years did sharecroppers or tenant farmers make enough to pay what they owed. So both groups of subfarmers tended to live in perpetual debt, and were allowed to remain on their lands only so long as they went on working it off.

Agee and Evans spent two months in Hale County, Alabama, living with three different tenant families. Or rather, Agee lived with them—Evans seems mainly to have stayed in a local motel. But Agee wanted to do more than simply interview the people. He wanted to merge with them, not as one of them but like an invisible man, a secret agent, who would sit there in plain sight. It would be a new kind of immersion journalism, reportage as Zola might have done it (the interiors of Agee’s farmhouses recall nothing so much as the miners’ shacks in Germinal). It wasn’t new, this approach—the Irish playwright John Millington Synge had done it for his Aran Islands, published almost thirty years before. But Agee brought to the assignment something of his own spirit, a zealotry about observation that verged on the missionary, mixed with shyness. A story goes that the night he met the Gudger family, he’d given them and some others a ride home from town—he was driving away from their house after a storm, and when he’d gone a short distance down the road, he semi-deliberately crashed his car, after which he was forced to hike back and ask for shelter. A means, perhaps, of forcing himself past the awkwardness of having to come out and say, May I stay with you? In that particular home he spent three weeks, “in deepest Alabamian rurality.”

That is the genesis, as everyone knows, of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, the book that appeared five years later—a strange book, which varying genres blow through in gusts. Among the enduring works of modern American prose, it’s a book whose admirers, when they’re being honest, will describe as exasperating. Undergraduate sounding in places—but with no less frequent moments of near-Keatsian sublimity—it’s a monument of regional fetishism. The title comes from the Apocrypha and smells of the lamp—of going through the Bible looking for a title—and feels basically meaningless, and is also wrong in its gender insistence, for a book whose most vivid portraits are of women, and highly erotic. The title is also wonderful somehow. One of those things.

This would be our business, to show them each thus transfixed as between the stars’ trillions of javelins and of each the transfixions: but it is beyond my human power to do. The most I can do—the most I can hope to do—is to make a number of physical entities as plain and vivid as possible, and to make a few guesses, a few conjectures; and to leave to you much of the burden of realizing in each of them what I have wanted to make clear of them as a whole: how each is itself; and how each is a shapener.

Listening, Annie Mae? You’re a shapener. And yet, a book that cannot be dismissed. Lionel Trilling—who saw Famous Men as marking the moment when ’30s idealism became self-conscious, entailing both a wisdom and a timidity—wasn’t being glib when he called it “the most important moral effort” of that generation in America. He wasn’t necessarily correct—the WPA’s ethnographic interviewing project, initiated in the very year of Agee’s visit, 1936, which involved scores of trained volunteers, who set out with early field-recording machines to capture the voices of a vanishing generation, a generation, black and white, that had survived the Civil War, seems both a morally greater undertaking (certainly it involved less grandstanding) and equally great as a work of nonfiction—but he wasn’t glib, either. You see what he means. There is something angelic about Agee’s looking. If you’re moved to picture Bruno Ganz in Wings of Desire, so evidently was Agee, more or less. “Reverent and cold-laboring,” he called his spying. Walker Evans, whom no one has ever accused of letting shit slide in the department of human observation, once wrote that for Agee, “human beings were at least possibly immortal and literally sacred souls.” If the writing occasionally seemed to strain after spiritual grandeur, it often enough achieved a spiritual grandeur. Consider this description of a primitive dogtrot cabin, a totemic form of southeastern architecture, known for its central breezeway (which the dogs would be always trotting through):

And this hall between, as the open valve of a sea creature, steadfastly flushing the free width of ocean through its infinitesimal existence: and on its either side, the square boxes, the square front walls, raised vertical to the earth, and facing us as two squared prows of barge or wooden wings, shadow beneath their lower edge and at their eaves; and the roof . . .

Steadfastly flushing the free width of ocean through its infinitesimal existence . . . Writers who can do that with English get to abuse it now and then. A man stands in a field looking at this house. The field becomes the ocean. The house becomes first a sea creature. Then a ship. Then it becomes a bird, or possibly a sea ray of some kind. The imagery seems to draw, as if from the very soil, the indigenous, heavily metamorphic religion of that country, the Native American spiritual system archaeologists used to call the Southern Death Cult. (“Town,” to people in that part of Hale County, was Moundville, Alabama, named for its Mississippian-era earthenworks, one of which was in that very year, 1936, ransacked by WPA archaeologists, yielding artifacts that would contribute to the formulation of the Death Cult theory. One of the most beautiful pieces of Mississippian art was taken from that mound, a jar with two incised hands on it. The hands have eyes on them.)

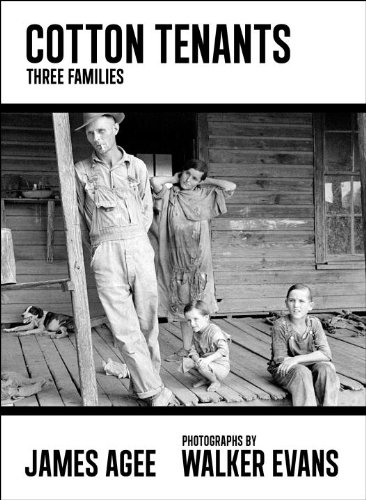

BEFORE THE FAMOUS BOOK, there was the essay, the thing Agee and Evans were sent to Alabama for in the first place. It never got published. Agee wrote it at least twenty thousand words longer than Fortune wanted; he turned it in late; the rubric under which it was supposed to run was done away with by editorial higher-ups, etc., etc. Anyone who’s written for magazines will recognize the thousand mystifying in-house obstacles that doom so many pieces. The very manuscript of this was considered lost, until Agee’s middle child and younger daughter, Andrea, found it a decade ago, and The Baffler excerpted it last year. Now, at the age of seventy-seven, it exists in full, published by Melville House with the title Cotton Tenants.

It’s a very different creature from the book. More restrained. More disciplined, overall—perhaps it’s more correct to say, more confident. Cotton Tenants knows its form: the long, weird, quasi-essayistic, documentary-infused magazine piece, a form older than the novel, despite a heritable instinct in critics to continually be calling it New. Agee was pushing the form—that’s partly what makes it exciting to see and read this new book. He was pushing Luce, too, seeing what he could smuggle into Fortune, stylistically, in a Trojan-horse kind of way. Later, writing for himself and Evans, he was willing to go further.

The earlier constraints had both limiting and salutary effects. It’s a smaller, lesser work, but a more perfect one. Prose is like glass in this respect. The bigger you go, the more opportunities for cracks. We cut more ambitious works slack not out of pity but in just measurement. There are places, like pressures, to which you can’t go without a little weakening of the structure. Cotton Tenants is a smaller pane of glass. Very clear. You can see Agee’s influences, in bud form, but you can also see a couple of years’ practice at writing what William Hazlitt called “periodical essays,” pieces that existed under a certain pressure to keep the attention of distracted readers. Agee had become good at it.

That’s the first thing to be said about this essay: Fortune was crazy not to run it. It was a failure of nerve, and a lost chance at running one of the great magazine pieces from that era. But who knows? It’s possible no one ever actually read it. I’ve worked at many magazines; you’d be stunned. Also: fifty pages on malnourished, fatigue-racked poor people? It was Fortune. Magazines do like having advertisers. Which only makes what The Baffler and Melville House have done more valuable.

Technically speaking, what the smallness makes possible is a sparseness. You hear it most clearly at the paragraph level. Gone are the torrents and flying buttresses of metaphor and self-analysis. Present instead is a steadiness of gaze. Less ecstatic; more patient and more painterly. In fact, it comes much closer than the book would to what Evans was doing with his pictures. And perhaps, five years on, feeling less obviously deferential to Evans as an artist, Agee felt more of a need to set his own contribution apart, or to insist on it.

Recently a scholar has argued that Agee’s prose became the feminine counterpart to Evans’s masculine photos. I don’t scoff at the idea. There was definitely psychosexual tension between the two of them. Evans slept with not one but two of Agee’s wives, and at one point Agee fantasized in print that he and Evans had participated in an orgy with a few of the tenant-farm girls and one of their fathers. Evans called this laughable. But artistic collaboration is a messy business. And Agee did believe, or at least entertain the theory, that what was most essential about the South was feminine, in the chauvinistic sense by which femininity equals possibility, availability; not that which impresses but that which is impressed upon. In a draft of the book—between the magazine version and what was published as Famous Men—Agee wrote, “In all the ways in which the South is peculiar to itself and distinct from all else it lay out there ahead of me faintly shining in the night, a huge, sensitive, globular, amorphous, only faintly realized female cell.”

There’s none of that kind of talk in Cotton Tenants. You do get curious opinions, such as that African Americans were not merely equal to whites but actually a “superior race.” Not that Agee paid much attention to blacks, in either of these works, but the force of white southern guilt, which has its own deforming effects to go along with or supersede those of southern racism, was strong with him. I wish he had written more about black culture. That isn’t really a criticism—he was doing a job he’d been sent to do; the magazine wanted cotton farmers, and more and more of those were white, a shift that had taken place in the years just before Agee and Evans arrived—it’s more just an expression of regret. How marvelous it would be to read him at length on the black southern music of that period, about which we know frustratingly little, in many respects, considering it turned out to be a dominant force in twentieth-century culture. (Something that also happened in 1936: Robert Johnson walked into a hotel room in San Antonio, Texas, sat facing the corner, and recorded “Come On in My Kitchen,” which if you want to talk about moral achievements . . .)

One of the best set pieces in Famous Men is a description of hearing an African-American rural male vocal chorus perform. Agee records that one of the landowners summoned a group of men for him and Evans, so that they could hear “what nigger music is like.” The two strangers do all they can “to spare them and ourselves this summons,” but the landowner will have his way. The men wore “pressed trousers, washed shoes, brilliantly starched white shirts, bright ties, and carried newly whited straw hats in their hands, and at their hearts were pinned the purple and gilded ribbons of a religious and burial society.” As the men sang, the eldest of them was “tapping the clean dirt with his shoe.” Agee writes that they sang “not in the mellow and euphonious Fisk Quartette style,” but in one “jagged, tortured, stony, accented as if by hammers and cold-chisels, full of a nearly paralyzing vitality and iteration of rhythm.” The landowner was proud of them, but as he watched, Agee remembers, the white man had “smiled coldly.” They do an especially weird number, “their favorite and their particular pride,” which Agee cryptically describes as “a sort of metacenter,” made up of

monotones between major and minor, nor in any determinable key, the tenor winding upward like a horn, a wire, the flight of a bird, almost into full declamation, then failing it, silencing; at length enlarging, the others lifting, now, alone, lone, and largely, questioning, alone and not sustained, in the middle of space, stopped; and now resumed . . .

The landlord complains that this is “too much howling and too much religion.” Agee is captivated; he knows he is witnessing something, but he can’t enjoy it. Throughout the singing, he feels “sick in the knowledge that they felt they were here at our demand, mine and Walker’s.” When he shakes the leader’s hand and gives him fifty cents, he tries “at the same time, through my eyes, to communicate much more.” The man thanks him “in a dead voice, not looking me in the eye,” doubtless thinking to himself, We just murdered that—why is he looking at me like he feels bad for me?

You get neither the tortuousness of that scene, in Cotton Tenants, nor the magnificence of it, of passages like “The tenor lifted out his voice alone in a long, plorative line that hung like fire on heaven, or whistle’s echo, sinking, sunken, along descents of a modality I had not heard . . . voice meeting voice as ships in dream.” What you get instead is a little ethnographic film made of prose. It finds a focal point that is intimate but stops just short of voyeurism—right where Famous Men chooses to keep going—and it sustains that, producing sentences like these, about the Tingle family:

There is about the younger children, about their skin and eyes and hearing and emotions, such an unsettling burn and brilliance as slow starvation can only partially explain. They are emotionally volatile as naphtha; incredibly sensitive to friendliness. You will possibly get the feeling that they carry around in them like the slow burning of sulphur a sexual precocity which their parents fail either to discern or to realize the power and meaning of: and the idea is somewhat borne out in the tone of their play together, and in the eyes of William, who is twelve, and in the wild flirtatiousness of Laura Minnie Lee, who is ten, and in the sullenness and shyness, flared across like burning sedge with exhibitionism, of Sadie . . .

In Famous Men, a passage like this would have returned like a boomerang to the metacenter of Agee himself, his conflicted reactions to his homeland and its people, what they did to him, internally. And that’s precisely what happens, in many places but chiefly in his writing about the girl he calls “Emma Woods,” the female most attractive to the sexually urgent Agee during his Hale County sojourn: “Each of us”—Evans and Agee—“is attractive to Emma, both in sexual immediacy and as symbols or embodiments of a life she wants and knows she will never have; and each of us is fond of her, and attracted toward her. We are not only strangers to her, but we are strange, unexplainable, beyond what I can begin yet fully to realize.”

Nowhere else in Agee’s work could you go to hear the sound of Cotton Tenants, not that I’m familiar with. This is not merely an early, partial draft of Famous Men, in other words, not just a different book; it’s a different Agee, an unknown Agee. Its excellence should enhance his reputation (as will, I expect, Dwight Garner’s forthcoming biography of him). This new book is most properly classed as a lost classic of that ’30s-era documentary renaissance, of which Evans was a part, and Zora Neale Hurston and Alan and Elizabeth Lomax and the WPA. Five years later he would take this tradition of journalism and inject it with powerful hallucinogens, creating something new, a book that did important documentary work while simultaneously x-raying, through the psyche of its own author, the assumptions underlying such work. That was a greater task. And Cotton Tenants shows us one of the reasons for its greatness: that before Agee transformed the genre, he paused and mastered it.

John Jeremiah Sullivan is a contributing editor to the New York Times Magazine and the author of Pulphead: Essays (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2011).