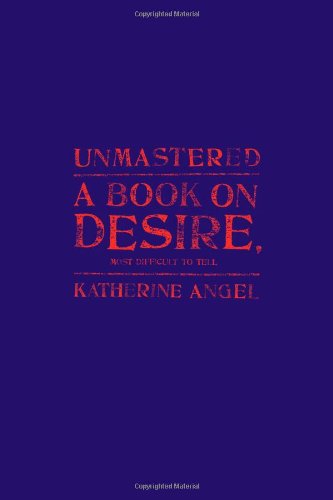

Once in a while a book appears that’s so bad you want it to be a satire. If you set out to produce a parody of postfeminist mumbo jumbo, adolescent narcissism, excruciating erotic overshares, pseudopoetry, pretentious academic jargon, and shopworn and unshocking “dirty talk,” you could not do better than Unmastered: A Book on Desire, Most Difficult to Tell.

One wishes that Katherine Angel, a historian of female sexual dysfunction at Warwick University, had, in fact, found this tale a little more “difficult to tell.” But Angel can’t stop telling and writing about herself—or about herself writing: “I have written a lot today,” she tells her lover complacently hundreds of lines into the stream-of-consciousness diary jottings that constitute her desultory exploration of female desire and feminism. “He knows,” she explains to her readers, that “I am writing about sex.” He does not, however, seem to grasp until that moment (if then) that his own sexual exchanges with Angel provide the book’s only tenuous narrative thread.

“‘You know,’” he says with the innocence of Candide, “‘I have just now put these things together: you and I have sex, and you are writing about sex.’ He laughs.”

In the groves of academe that Angel inhabits, sex is anything but a laughing matter. The relation of Anglo-American academics to sexuality remains a troubled one—at once obsessive and puritanical, criminalizing and infantilizing—even in our day and even (or especially) in disciplines specifically devoted to gender studies. This is a culture where a graduate student can cry sexual harassment if her academic adviser closes his door during office hours, but turn around and solicit congratulations for personal tell-alls bearing titles with some variation on Vagina, which inflict far more violence on her intimate space than any indiscretion she’s ever charged. (More or less, this is the career path of Naomi Wolf.)

This culture finds itself so on edge about all things erotic that any departure from its usual standard of repression is mistaken either for crime or—ironically—for art. A tap on the knee quickly becomes an act of abuse, but a four-letter word in the book of an academic quickly becomes an act of genius, of revolution, of daring.

Angel alludes to her writing about sex with a curious combination of pomp and puerility. Hundreds of lines after her talk about it with her lover, she has a talk about it with her mother.

“I mention the writing,” she tells us.

“I’m very curious, Katherine,” says Mom, “to know what this book is about.”

“Well,” says Angel with hushed awe, “it’s about, you know—S-E-X.”

The reader veers from one such instance of schoolgirlish self-regard to the next, for the way Unmastered is structured, there are often just a few lines on each page—and sometimes only four words—which means that the book’s 368 pages may, in fact, amount to no more than 368 times 30 words.

Angel seems to believe that her words are poetry and best savored in small and highly concentrated doses. A disturbing number of reviewers and blurbers have given her credence: “It’s hard to overestimate . . . [the] exquisite sensuality” of Angel’s book, its “artfulness” and “richness,” wrote Observer editor Olivia Laing, in the United Kingdom, where Unmastered first appeared in 2012. In the United States, Publishers Weekly recently called the book “ghostly and poetic.”

Here is a sampling of the words Angel singles out for readers’ especial attention by placing them alone in the center of an otherwise pure, white, empty page:

Fuck me. Yes, fuck me!

I know what he means.

This thing in there. All that. These.

Let the boy win at tennis!

It’s OK, it’s OK. I’m really not that hungry.

I am so fucking hungry!

Fuck, he says, when he’s inside me, Oh fuck.

Dupe. Collaborator. Victim.

Fuck me. Yes, fuck me!

Peck peck!

Peck peck!

This is not to say that the book skimps on longer and more pseudoscholarly discussions: Indeed, Angel exhibits an all-but-omnivorous appetite for academic obscurantism. There’s nary a man in Unmastered who is not referred to as a “hypostasized man,” or a mother who isn’t a “hypostasized” mother, or indeed a “reality” that is not “hyper-real.” Between parades of four-letter words, Angel makes time to celebrate “postmodern intertextuality,” “heteronormativity,” and the “space for non-normative pleasure.” She quotes and misquotes Michel Foucault, Virginia Woolf, and Susan Sontag. Perhaps most important, she relates her intrepid educational adventures in seminar and lecture rooms around England.

If ever you were a graduate student, and felt your seminars were too short, this book is for you. Katherine Angel is eager to fill you in on all the points she always wanted to make as a seminar student but was afraid to broach.

“Oh. My heart sinks,” she remembers feeling in a class she was taking on pornography once. “That feeling, again: wanting to ask a difficult question. I am going to be the one to break the mood, to interrupt that cozy feeling of consensus.”

Her professor had decided to challenge the time-honored feminist truism that pornography is uniformly bad by remarking that there are redeeming aspects of it. Pornography, he proposes, “undoes the stigma of non-normative sexualities and bodies: of fat bodies, of hairy bodies, of small bodies. . . . [It] is democratic,” he claims, and perhaps even “educational. . . . It can show you ‘what goes in where.’” The class is apparently betraying some assent.

And what does our fearless author want to ask? She wants to ask whether pornography is truly all that perfect. But she can’t quite drum up the courage.

Not until the next class anyway.

“So, here I am, again,” she tells us.

My hand is up. I am asking Mr. Pornography: “Given that for many women, orgasm during vaginal sex is elusive, and clitoral stimulation is crucial, how then is clitoral pleasure represented in the swathes of pornography you have surveyed?”

There is a flicker of unease across his face.

Angel has got him!

There is a pause. Oh. . . . He seems a bit unsettled. A little bit flummoxed.

She has won! “Surely—surely—someone must have asked him in his years of research. Nothing comes. I don’t want to press the point home—why not, I wonder? Why not make this point more forcefully?”

The Quiet Conqueror, the Unmoved Mover, the Jeanne d’Arc of Cultural Studies! How merciful—and touching and girlish and, yes, sexy—that Katherine Angel does not want to drive the point home too hard on her seminar teacher, to hoist him by his own petard. Perhaps it has something to do with that other ambiguity she alludes to in the book, that women—even feminists—don’t necessarily want to be on top. At least she doesn’t.

When she’s in bed with her boyfriend, the “hypostasized” male, she likes him to dominate and even asks him to tie her up at one point. (“I want to say crazy stuff,” she whispers, as though she’d invented this sexual cliché.) She prefers “being fucked” to “fucking,” and even cites a journal entry of Susan Sontag’s that explains that you, the sexual partner, are more “gone” that way.

For yes, in the morass of narcissism that is this book are buried some timid, clichéd points that have been made much more forcefully and memorably by others. There is the point that strong women do not always want to be strong in bed. (See countless superior essayists on the subject, from Simone de Beauvoir to Katie Roiphe—or see such little-known novels as Fifty Shades of Grey, or such recent memoirs as Alisa Valdes Rodriguez’s The Feminist and the Cowboy.) With the near mainstreaming of BDSM today, it will soon be the opposite that needs defending—so-called vanilla sex.

And there is the point that pornography is both good and bad. The author views porn herself. But that does not mean she is without criticism of it!

The argumentative upshot of this book is: Things are complicated. It is an academic cliché, hardly something for which you normally expect an intrepid scholar to go to bat. But Angel feels she carries a very big bat indeed, or a big stick—outside of bed, if not actually between the sheets.

It’s not what she does with the stick that’s the problem—her book perfectly adheres to the Hippocratic oath: It does no harm. It is far too blunt edged and flaccid. Its author is far too self-absorbed to focus at any length on any subject apart from herself.

The victim, in these pages, is outside of them: The victim is good prose, and—to the extent that Angel pretends to write poetry and reviewers have called her work “lyrical”—the victim is also the concept of poetry.

Why is it that a book as bad as this garners reasonable reviews and makes it to America from the United Kingdom? The answer seems to lie in the combination—if not the quality or authenticity—of the ingredients. Unmastered purports to combine philosophy with fellatio, intellect with erotica. It allows us to be voyeurs and lawyers at the same time. It gives us a good conscience reading porn.

But in truth? Unmastered does porn a disservice. Not to side with Angel’s maligned professor, but real porn is a lot more “democratic” than this: It includes flesh-and-blood people—not the two-dimensional “hypostasized” extras of this book. It also focuses on a few different body parts—not only on the author’s navel.

Cristina Nehring is the author of A Vindication of Love: Reclaiming Romance for the Twenty-First Century (Harper, 2009) and Journey to the Edge of the Light (Kindle Singles, 2011). Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Atlantic, Harper’s, Slate, New York magazine, and Condé Nast Traveler.