Since the late 1990s, cable television has yielded up a fresh batch of the sort of selfish, morose, profane, scheming, sometimes violent, sometimes seriously ridiculous male characters we used to have to seek out in movies by Sam Peckinpah and David Fincher, in novels by Philip Roth and Cormac McCarthy, or in the poetry of John Berryman and Frederick Seidel. Grunge music for the eyes, this new brand of TV offered an escape valve for the pent-up anger and frustration of many real-life producers, writers, and directors who were suddenly freed from the constraints of network sitcoms and genre dramas.

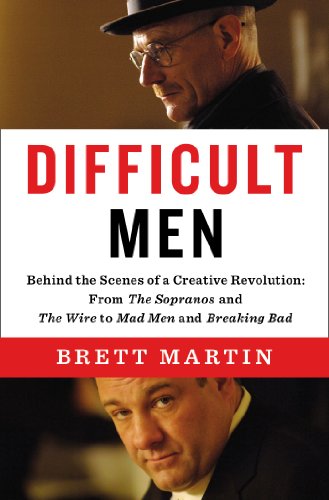

It is from this cohort that Brett Martin pulls in Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution: From “The Sopranos” and “The Wire” to “Mad Men” and “Breaking Bad” (The Penguin Press, $28), a vastly entertaining and insightful look at the creators of some of the most highly esteemed recent television series. Not merely a collection of profiles of, among others, David Chase (The Sopranos), Matthew Weiner (Mad Men), David Simon (The Wire), David Milch (Deadwood), and Vince Gilligan (Breaking Bad), Difficult Men lays out a history of the TV industry from the late 1990s to the present, demonstrating how a confluence of pay- and basic-cable broadcasting philosophy, new profit paradigms, and the rise of the cult of the “showrunner” (i.e., the producer given the most credit for the guiding aesthetic of a series) has reshaped the business, together with a boom in online fan commentary. Along the way, Martin also carefully explains just how all these forces combined to yield both high-quality TV and the enabling of some mighty big, needy, neurotic egos.

Martin’s book is crammed with pungent anecdotes about, and quotes from, people who have collaborated with these “difficult men”—or at least tried to. You think Tony Soprano was cold-blooded when he strangled a mobster while taking his daughter on a college tour in a famous first-season episode of The Sopranos? Tony’s creator, Chase, may have gone his character one better when he told one of his assistant producers (Todd Kessler, who’d go on to cocreate the Glenn Close series Damages) that “I’ll never be truly happy in life . . . until I kill a man . . . not just kill a man, but with my bare hands.” Producer Steven Bochco (Hill Street Blues, NYPD Blue), who gave Milch his start in the industry, describes Milch’s strategy for success as a writer-producer: “He became the absolute center of a completely dysfunctional universe”—a universe, Martin documents, in which Milch would abruptly halt production of the show in order to dictate script changes to an underling. For good measure, Martin notes, this artist-boss ginned up enthusiasm among his staff by “randomly handing out hundred-dollar bills,” while being, as even one of his more admiring ex-employees says, someone who could never be pleased by others’ work.

These two cable impresarios alone would be sufficient to justify the book’s title. But Martin reserves special, goggled near disbelief for the blithe egotism of Mad Men’s Weiner:

Though he treated upcoming plot developments with the solemn secrecy of nuclear codes, once they had aired, Weiner was willing to expound at astonishing length upon themes, references, callbacks to previous episodes, inside jokes, important costume decisions, and other aspects of his grand design. “Wasn’t that amazing?” he would say. Or, “That was hilarious.” And it would take an interviewer—used to the usual rules of human discourse—a moment to remember that Weiner was speaking unabashedly about his own work.

Weiner seems to operate on the emotional level of a brilliant three-year-old. Mounting a chair in the midst of a triumphant first-season Mad Men Golden Globes win, his sad best instinct was to squeakily bellow, “This is what you wait for, so you can tell all those people who ever said anything bad to you to go fuck themselves!”

Martin is acutely attuned to the different ironies layered into his subject. One is that these problematic fellows are all loudly contemptuous of the auteur theory (typical is Gilligan: “The worst thing ever the French gave us is the auteur theory. It’s a load of horseshit. You don’t make a movie by yourself, you certainly don’t make a TV show by yourself”) while they also claim near-complete authorship of their shows, regardless of the degree of collaboration. Martin’s extensive reporting occasionally even allows him to pit one difficult man against another. Thus Weiner, who once chafed as a Sopranos staff writer at Chase’s hogging of writer credits on scripts, ended up institutionalizing such practices in his own successful cable franchise: “As The Sopranos proceeded, [Chase] added his name to the authorship of scripts. . . . Weiner, though, brought the practice to an entirely new level [on Mad Men]. He adopted a rule that if more than 20 percent of a writer’s script remained, he or she would retain sole credit. If not, Weiner added his name.” The result? “Of sixty-five episodes through season five, fifty were at least partially ‘written by’ Weiner. It became enough of an industry inside joke that it was the subject of a sight gag on 30 Rock.”

Martin’s stated goal is to recount the culmination of what he calls the “Third Golden Age of Television” (after the industry’s start in the ’50s, and its development of sophisticated storytelling in the ’70s and ’80s). And he does so with his own sophisticated synthesis of reporting, on-set observation, and critical thinking, proving himself as capable of passing judgment, of parsing the strengths and weaknesses of any given TV show, as any reviewer who covers the beat. No TV critic, for example, has come up with a better concise take on Milch’s Deadwood:

One of Milch’s great themes was the loss of religious ritual as the central organizing principle of the modern world—and what flows into that vacuum to replace it. . . . This both was the subject of Deadwood—as the muddy community groped fitfully toward some kind of organization—and, to [Milch’s] mind, what explained the moment in history that allowed the show to exist, at the expense of what had once been the dominant mode of popular entertainment: film.

Such critical insights open out, in turn, onto an important subtext that runs beneath the testosterone-heavy reportage in Difficult Men. Unlike film or rock criticism, television criticism has never yielded a significant body of work—or at least an acknowledged one enshrined with any permanence in book form. Who have been TV criticism’s Pauline Kaels, its Andrew Sarrises? James Wolcott began his career writing fine, Kael-ite TV reviews for the Village Voice, but has since spent much of his time nosing through books and politics. There have also been the Washington Post’s Tom Shales (who won the first TV-criticism Pulitzer for a body of work that is now, alas and for all the energy of his prose, all but unreadable) and the peripatetic John Leonard (who never won a Pulitzer for his TV criticism, but deserved to, and whose between-covers work remains fresh and vital).

As Martin points out, a good deal of the anemic state of TV criticism can be traced to the rise of a new genre of writing about television. Such criticism in the past decade has been largely subsumed within a different enterprise that paralleled the ascent of the “difficult men” era: “the strange and telling practice of ‘recapping’—which became the dominant way of talking about these shows on the internet.” Martin notes that online recaps of shows, which place an obvious premium on near-real-time audience reaction, leave precious little room for more considered writing about what TV drama really is and how it works:

Recaps were precise, moment-by-moment retellings of an episode just aired. They may have been an opportunity for editorializing and snarkiness, but they also smacked of ritual reenactment—not unlike a young writer fastidiously typing out a favorite short story, word for word, in an attempt to commune with its author.

Exactly: “An opportunity for editorializing and snarkiness”—that’s what has passed for TV criticism in many outlets. And within this genre, the alleged critic’s “attempt to commune with [a show’s] author” is an accurate description of the communication that goes on constantly, on Twitter and in cozy interviews conducted by critic and showrunner, sharing their thoughts on and interpretations of any given show. This frenetic traffic in pseudoinformation about television and TV culture also figures prominently into the work of every single one of the guys profiled in Difficult Men.

But recapping is ultimately a mug’s game—there is no way to maintain that kind of writing without becoming either burned out or a hack. And beyond the difficulties of sidestepping those occupational hazards, there remains the challenge of creating diverse aesthetic principles that rise above the Internet’s limited range of extracritical responses, which typically run the gamut from this-is-awesome! blog posts to fitfully edited twelve-thousand-word essays about this or that show’s elaborate “mythology.” Among those asking the proper artistic questions are Alyssa Rosenberg, blogging for ThinkProgress.com, Tom Carson at GQ.com, and Matt Zoller Seitz at New York magazine’s Vulture. As Martin’s book argues, great TV must be interpreted and challenged by great TV criticism. Male egos may grow lush under the adoring gaze of online fanboys and fangirls. But as Martin’s vivid and idea-packed study makes plain, the best way to make sense of our culture’s difficult men, on- and offscreen, is to subject them to rigorous, if often admiring, scrutiny—in short, the sort of criticism that must now extend to television as much as it does to any other first-rate art.

Ken Tucker is a cultural critic who has written about TV, books, and movies for the New York Times and New York magazine.