Ugliness was fun for a while, but then it got too real. After kitsch—which bottomed, or perhaps topped, out in the middle of the last century—came a dark commercial anti-kitsch, an ugly so enveloping and horrid that it couldn’t be celebrated. Mass culture and aspirational brand culture drove right into each other, merging into a hideous beast that vomits Target “designer” lines and QVC frocks and polyester “fleece” blankets in sunny colors. There’s nothing charming about the ugliness that governs how we buy what we live with now. All that’s worse is the production regime under which it’s all made.

The evolution of Abercrombie & Fitch from Bruce Weber’s aching black-and-white soft-core catalogue to mass-market Sensurround menace tells the story of our rush into ugliness. The biting stench pumped out from Abercrombie’s Hollister store at 666 Fifth Avenue (a suitably chiliastic address) wafts down the line of stunned tourists. Before them, a bank of blued-out monitors shows waves on the Pacific coast, allegedly crashing ashore in real time. Across a tiny sort of moat, there are greeters at the door—often shirtless, always emaciated—who speak less coherently than their other, better-known theme-park-animal brethren, Mickey and Goofy. The stuffed shopping bags the tweens and their parents leave with are printed with images that are downright lewd.

This is awkward. Is there any reason to tote about town an image of the absurdly idealized and sexualized male body when we can all see that both you and we are so much uglier?

And then what happens when you take that bag back to your ugly home in America, which is more likely than not too big to keep cool or warm enough with the seasons? In the ugly schools, the kids all wear Hollister shirts unless they wear shirts from Hot Topic, the allegedly countercultural alternative. They have a new shirt that says “YOLO? STFU,” and it has a picture of Grumpy Cat on it. Good stuff. Hot Topic is also pimping shirts with close-up pictures of goats and sloths. Camp, at least, is back for another ugly, flailing round—but this time it’s earnest, and it lends itself to retweetable expressions only.

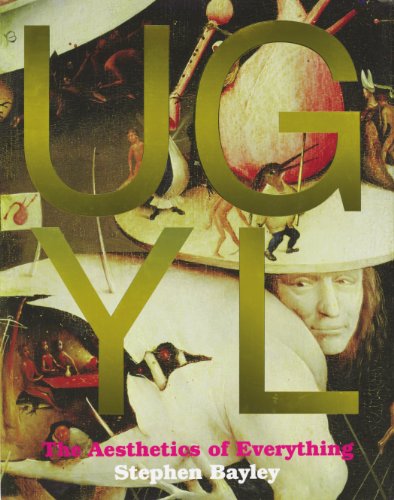

Stephen Bayley’s Ugly: The Aesthetics of Everything (Overlook, $40) is a terrific history of white people’s thoughts on the beautiful and the tacky. Bayley plumbs the shallowest depths of white culture of the last few hundred years, from high kitsch (snow-globe collections, the infamous Madonna Inn), to the compelling ugliness of plants, animals, disfigurement, and racism, to the reactionary pro-ugliness movements of punk and modernist architecture.

Bayley is a big fussy deal in the UK. He was the inaugural director of the Design Museum, and his bio always notes that he is a consultant—a duty he’s sometimes rapturously described as performing “at the highest level”—for brands such as Ford and Coca-Cola. He has also written or compiled at least a dozen books. (Of 2009’s Woman as Design, he wrote: “Feminists of the dinosaur and dungaree era thought it a misogynistic travesty by a knuckle-dragging sexist ape.” Excellent, we will avoid it, then.)

He dismisses Ugly as a “suggestive essay,” which is about right—he runs from Nagasaki to the Fontainebleau to Robert Smithson as fast as possible. The only delightful place he’s apparently missed is the Sandwich Glass Museum on Cape Cod. He’s best on weird historical nuggets, like a show at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1852 that displayed hideous objects so as to instruct visitors on “the correct principles of taste.” (Please alert the Cooper-Hewitt, as it’s high time to revive this practice.) And he’s quite right in explaining how cities were once made ugly by manufacturing; since we’ve exported all that to far-off lands, our cities have started to become prettier playgrounds for the well-off.

But the strange little silence that proves ugliness has won overall is that Bayley almost never touches anything after the year 2000. Not the work of Grayson Perry or Rachel Harrison, or any other artists who work politically or expeditiously in ugliness, and not 9/11 or 7/7, and not, say, Marc Jacobs—neither the clothes, the brand, nor the man himself. (One rare exception: the reviled Arquitectonica Westin Hotel in Times Square, completed in 2002, but planned in the mid-’90s.) It seems that the ugliness branded during this millennium is just too much for even a strong-stomached interpreter like Bayley. It doesn’t photograph well. It’s actually sad.

And whose problem is it? In America, ugliness—particularly sordidness—is a problem for all. Bayley never takes us beyond Europe and America, with the exception of a wee excursion to Australia and a brief discussion of a Turkish town. The problems of ugliness in America are different for rich and poor, but at least we know that ugliness manifests itself in a rainbow of expressions and flavors. Still, this is a very good coffee-table book for white people and admirers of their culture, particularly because you can eventually read the words if you get terribly bored in your beach house. Just don’t look up at your design choices, as they grow ever more dated and stale. The best-case scenario, in view of all this onrushing aesthetic squalor, is that we’re all on the long slide from trendy to camp.

Choire Sicha is the author of Very Recent History (Harper, 2013).