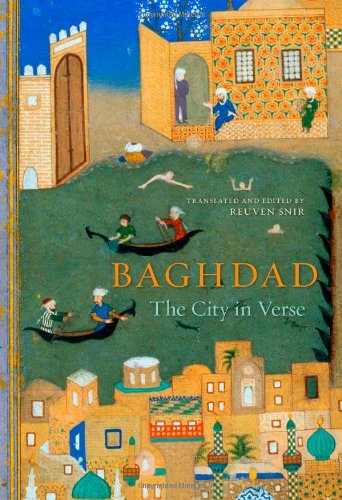

An Arabic poem about Baghdad, like a Hebrew poem about Jerusalem, inevitably evokes the collective memory that binds the place, the language, and its people together. Iraq’s 1,251-year-old capital was built by a Muslim empire that held the torch of civilization in the eighth and ninth centuries. In the thirteenth century it was sacked by Mongol invaders who, according to legend, made the river Tigris flow red with blood and blue with the ink of books from the city’s great libraries. It was resurrected in the twentieth century by modern state builders who made it a capital of tolerance, prosperity, and Arab nationalism—only to be ruined again by a dictator and his wars and further destabilized by American occupation. A vigorous yet densely complex poetic tradition has traced popular memories of this tumultuous history, and a small portion of that literature can be found in Baghdad: The City in Verse, a sleek and informative volume edited by Reuven Snir, a professor of Arabic literature and dean of humanities at the University of Haifa. The book presents roughly two hundred poems about the city—mainly authored by Baghdadis from a range of historical periods—in chronological order, beginning with “Stars Whirling in the Dark,” by Muti‘ ibn Iyas (704–785), and ending with “Baghdad,” by Manal al-Shaykh (who was born in 1971). For context, Snir also provides a substantial introduction that weaves the poets’ voices into his own buoyant narration of Baghdad through time.

The fabled “round city” of the eighth and ninth centuries—the Islamic Abbasid empire’s political and commercial capital—was also one of history’s great intellectual hubs: The caliph Al-Ma’mun amassed the largest repository of books in the world, and endowed a multigenerational translation movement to preserve seminal ancient texts of science, philosophy, mathematics, and many other fields. The caliph’s institute of higher learning, Dar al-Hikma (the “House of Wisdom”), also sponsored scholars who built on these texts to innovate new disciplines, most notably algebra. Snir’s selections from this period reflect the city’s luxuriance—a place where “breeze reviv[es] the sick, / blowing between sweet basil branches,” in the words of ninth-century poet Mansur al-Namari, who is still taught in Iraqi schools today. But the book also provides a platform to the underclass, through poems of disaffection that challenge the seamless narrative of a resplendent city. “Baghdad’s residents have no pity for the needy, / no remedy for the gloomy,” writes an anonymous poet. “Mean as they are, amazingly so,” says another, “for goodness sake, why have they been allowed such a paradise?”

By letting in outcast voices such as these, Snir helps puncture a variety of present-day assumptions about Baghdad and the broader Muslim region. That Baghdad was and remains a capital of Islam is borne out by the history Snir highlights: Today’s four schools of Sunni Islamic law were canonized in the medieval city, and a large community of political dissidents known as shi’at Ali (the partisans of Ali) crystallized into Islam’s minority sect there. But some of the book’s poems show the city to have been a hub of worldly indulgence, at odds with modern perceptions of Muslim capitals as religiously conservative. One poem from the eighth century is set on a Baghdad morning, “in a house where glasses are akin / to stars whirling in the dark among drinking companions. / . . . I was still drinking when sunset arrived, / between melodies of castanets and lute.” Eleventh-century poet Abu al-Ma‘ali speaks to an unbridled sexual culture when he describes the opprobrium he stirs by going out with a bearded boy, as opposed to the more conventionally appealing smooth-skinned type: “Look for another! they urged. / In that case I will never be pleased, I replied. // If his saliva were not honey, / the bees would never have invaded his mouth.”

Other aspects of Baghdad’s history to which the poems draw attention may be just as surprising to some Iraqis as they are to Western readers. Baghdad’s once vast Jewish community, for example, has been written out of Iraqi textbooks for more than three generations. Snir was born in Israel to two Baghdadi Jewish émigrés who, along with nearly 125,000 other Jewish natives of the country, were forced to leave Iraq in 1951. The community’s continuous presence in the lands of Iraq dates back more than 2,600 years, well before the founding of Baghdad in 762 CE, to the exile of Israelites to Babylon after the destruction of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem. Snir cites Ottoman and British statistics from the early twentieth century finding Baghdad’s Jews to make up more than 30 percent of the population, and he describes their thorough integration into the local commerce, politics, and culture. The book includes several poems by Jewish writers, barely known to Iraqi Muslims today, that reflect their love for and identification with Iraq, as well as the pain of falling prey to its tyrants: “My adherence to Moses’s creed / diminished not my love for Muhammad’s nation,” writes twentieth-century poet Anwar Sha’ul. Iraqi-Israeli poet Ronny Someck bitterly describes his experience of the Iraqi Scud-missile attacks on Tel Aviv during the 1991 Gulf War: “Oh Tigris, Oh Euphrates—pet snakes in the first map of my life, / How did you shed your skin and become vipers?”

Iraqi nationalist narratives tend to say little about the five hundred years between Baghdad’s first “golden centuries” and modern times—except that they were a period of darkness marked by the Mongols’ destructive invasion of 1258 and Tamerlane’s conquest in 1401. Snir’s introduction does not attempt to fill in the period’s many gaps, and the compilation contains no poems written between the thirteenth and eighteenth centuries. But Mongols appear repeatedly in poems from the modern period—often as a metaphor for more recent foreign invaders as well as domestic tyrants. “Poetry Presses Her Lips to Baghdad’s Breast,” a poem about life under military dictatorship, compares the Baghdad of 1258 with that of 1969: “The first, the Mongols destroyed; the second, / her children do the same.”

An apparent mistake in the compilation, also in its pages covering the modern period, speaks to a larger problem related to the impact of tyranny on historical memory. The book includes a translation of the 1999 poem “Hulagu” (the name of the Mongol conqueror): “Oh Hulagu of the present time, / Remove from me the sword of oppression.” Its author, Su‘ad al-Sabah, is in fact neither Baghdadi nor Iraqi, as her presence in the compilation implies. She is a Kuwaiti national who, during the Iran-Iraq War, visited Iraq and praised Saddam in verse for defending the “eastern flank of Arabism” from “Persian” invaders, only to reverse her opinion of the Iraqi dictator upon his invasion of her country in 1990. By the time she wrote “Hulagu,” she had been estranged from the Iraqi capital. For Kuwaiti nationalists like al-Sabah, Baghdad itself is an invader.

In modern times, violent conflict between Iraq and its neighbors has placed political impositions on the national discourse that distort Iraqi historical memory and contribute to the difficulty of establishing a Baghdadi literary canon. In the course of ten years of fighting with Iran, the Iraqi state sought to erase the historical role of Persians from Iraqi books and public discussions—much the way the Jewish history of Iraq had been wiped clean two generations earlier. In doing so, it denied Baghdadis an understanding of the essential role Persians—and Persian-Arab convivencia—played in constructing their city’s “golden age.” In fact, the bureaucratic foundations of the early Abbasid state were the vestiges of the Sassanian Persian empire that it supplanted. Many of the most prominent scholars in the fabled medieval “House of Wisdom” were Persian—including the pioneer of algebra, al-Biruni, and the medical scientist Avicenna. Snir’s introduction omits all of this. Nor do we learn that the Baghdadi poetry of the period that is the heart of Snir’s book—the eighth and ninth centuries—was part and parcel of the syncretistic creative environment that flourished between the two cultures: Ninth-century poets Ishaq al-Khuraymi and Tahir ibn al-Husayn al-Khuza‘i, each translated in the compilation, used both languages and hailed originally not from Baghdad but from the ethnically Persian province of Khorasan, now a part of Afghanistan.

Baghdad’s ethnic, religious, and historical complexities make it difficult to translate the city’s poems without providing layers of context. The challenge is compounded by the fact that traditional forms of all Arabic poetry are valued partly for their grammatical and syntactical calisthenics, unique to the language and difficult to render. Add to this the problem of selective memory: As evidenced by the obscurity of Baghdadi Jewish culture in Iraq today, awareness of particular poems is often a function of their propagation or repression by a tyrant to serve a sectarian or ideological goal. Thus the choice of material to translate can raise political and even moral questions.

On the whole, Baghdad: The City in Verse meets these challenges admirably in providing a deeply affecting compilation to illuminate, for English readers, the Iraqi capital’s rich and enduring legacy. Many Americans whose limited view of the city was largely informed by the US-led invasion have now lost interest in the plight of Iraq. Snir brings to life the city of his love—an “aria of bracelets and jewels, / . . . treasure of lights and perfumes.” In doing so, he offers a corrective to warped perceptions of Baghdad and a reasoned hope for a better future inspired by its resplendent past.

Joseph Braude is the author of The New Iraq (Basic Books, 2003) and The Honored Dead (Spiegel & Grau, 2011).