In the spring of 1947, when German-émigré film scholar Siegfried Kracauer published his groundbreaking history of Weimar cinema, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, theater critic Eric Bentley accused him, in the pages of the New York Times, of being “led into exaggeration” by hindsight and pursuing a “refugee’s revenge.” It’s true that Kracauer, who barely managed to flee Nazi-engulfed Europe on one of the last ships to leave the port of Lisbon, had some difficulty retracing the course of German cinema in the period between the wars without recalling the horrors that he by then knew had taken place in its aftermath. He could no longer look, for example, at the unruly students in Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel (1930) and not dwell on the pernicious Hitler Youth that would gain prominence soon after the film’s release.

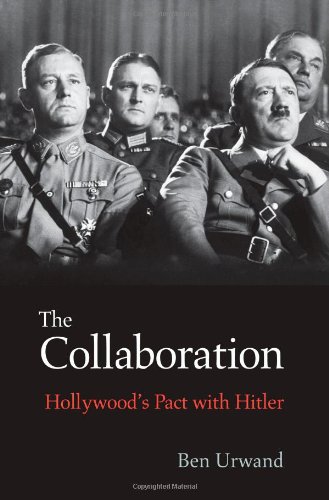

Ben Urwand’s recent book, The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler, suffers from some of the same retroactive historical interpretation for which Kracauer was once taken to task. It sets out to prove that there were deep ties between major Hollywood studios and the Nazi government. It, too, has elicited a series of strong reactions in the wake of its publication in early fall. (Widespread media attention over the summer, in the New York Times, Tablet, and the Chronicle of Higher Education, led Harvard University Press to release the book a month ahead of schedule, while the outpouring of skeptical reviews that soon followed has muffled much of the initial buzz.) Indeed, the book has sparked the kind of heated controversy not seen in academic circles since Daniel Goldhagen first published his similarly strident work Hitler’s Willing Executioners in 1996.

Much like the Goldhagen controversy, the reaction to the publication of The Collaboration has made public a sharp divide between the views of a young, renegade Harvard professor and those held by the leading figures within the academic and critical establishment. In both instances, rhetorical bravado and sensationalist terminology (“eliminationist anti-Semitism” in the case of Goldhagen, and “collaboration” in the case of Urwand) have been met with suspicion and with recurrent pleas for greater complexity, a wider frame of comparison, and more sensitivity to historical context. (In the most extreme response to The Collaboration, New Yorker critic David Denby urged Harvard University Press to recall the book, on charges of “omissions and blunders.”)

In order to build his case, and to expose what he sees as not merely greed, cowardice, and opportunism on the part of movie moguls but outright collaboration with Nazi officials, Urwand marshals his evidence with the zeal of a criminal prosecutor. What begins, innocently enough, as an attempt to reveal “the complex web of interactions between the American studios and the German government in the 1930s” very quickly becomes a matter of defending, as best he can, his claim about the vast extent to which Los Angeles–based German consul Georg Gyssling censored American movies and controlled their leading producers.

To amplify his case, and to insinuate the sort of morally dubious Faustian bargain evoked in the book’s hyperbolic subtitle, Urwand structures things around Hitler’s own primitive rating system: “good” (yes, he liked Mickey Mouse and Laurel and Hardy), “bad” (he didn’t care much for Tarzan or for the “traitor” Marlene Dietrich), and “switched off” (movies, like The Mad Dog of Europe, that Hitler and his man in Hollywood purportedly kept from being made). Urwand finds further evidence of “collaboration” in the release of Hollywood films in Nazi Germany that held a special appeal: When a critic from the Völkischer Beobachter declares that King Vidor’s Our Daily Bread (1934), a Depression-era drama, promotes the “leader principle,” Urwand takes him at his word; and when a short clip from The House of Rothschild (1934) gets repurposed in Fritz Hippler’s infamous anti-Semitic mash-up Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew, 1941), Urwand insists that the latter film “was unthinkable without The House of Rothschild.”

Urwand is so eager to be right that he sometimes willfully omits examples that would disprove or at least complicate his account. He doesn’t address, for example, any Hollywood films with an antifascist thrust, such as Fury (1936), the first American picture Fritz Lang made for MGM (a company that serves as one of Urwand’s favored targets) after fleeing the Nazis, or the Warner Bros. films Black Legion (1937) and Juarez (1939). He quotes selectively from documents (failing to include Harry Warner’s fiery testimony in his account of the September 1941 congressional hearings held by the isolationist faction in the US Senate), shies away from necessary contextualization (the harsh censorship restrictions imposed by the British, the Japanese, or even the states of the Jim Crow South), and ends his book with a rather bizarre, ahistorical suggestion of guilt by association (the final photo has Jack Warner, of Warner Bros., and Harry Cohn, of Columbia Pictures, standing on “Hitler’s personal yacht” during an army-sponsored cruise along the Rhine in the weeks after Germany’s surrender).

Even if he focuses chiefly on films made in the 1930s, Urwand cannot prevent himself from fixing his eyes on what came after, holding the business-minded studio executives accountable for not knowing what we know now. When asked about the larger stakes of his book, Urwand, the grandchild of Holocaust survivors, recently told a reporter for The Australian: “The victims are not a small group of Jews in Los Angeles, not the Jewish studio heads. The victims are the six million Jews who had no one to speak for them and who died. . . . That’s the important story to tell here.” While that may be an important story, its bearing on the methodological approach he takes in The Collaboration is ultimately so overpowering as to skew his account and to cause him to play, as critics once accused Kracauer of playing, a “prophet in retrospect.”

Noah Isenberg is the author of Edgar G. Ulmer: A Filmmaker at the Margins (University of California Press, 2014). He directs the Screen Studies program at the New School.