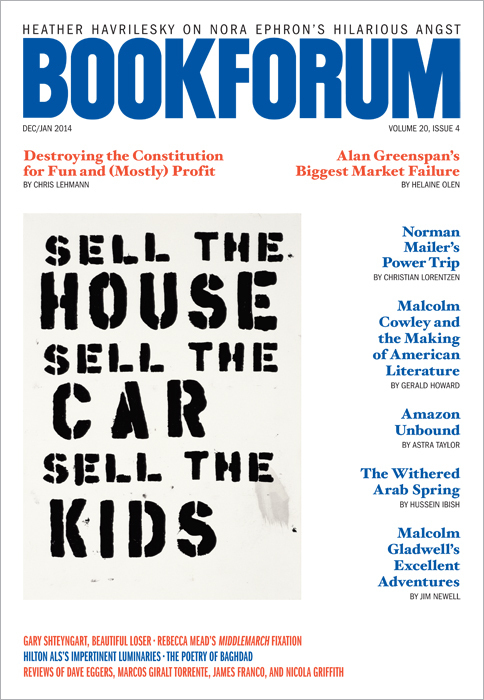

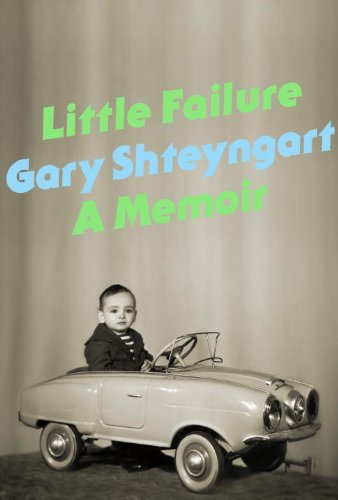

The germ of Gary Shteyngart’s honest, poignant, hilarious new memoir, Little Failure, was planted in 1996, when he was a recent college graduate, living in Manhattan with “a ponytail, a small substance-abuse problem, and a hemp pin on his cardboard tie,” his novelist dreams still out in front of him. Browsing at the Strand Annex during his office-job lunch hour, he came across an enormous coffee-table book called St. Petersburg: Architecture of the Tsars. He had a sudden, severe panic attack when he saw the photo of the pink Chesme Church on page 90; he had lived nearby as a very small boy. “What happened at the Chesme Church twenty-two years ago?” he asks the reader rhetorically.

The reader would be wise to put on his seat belt and settle in for the ride; it will take more than three hundred pages to find out, because Little Failure is both an excavation of—and a cathartic, self-directed recovery from—this memory.

The author was born Igor Shteyngart in Leningrad in 1972, during the twilight of the Soviet Union, and grew up as the asthmatic, tiny, bookish only child of two perennially fighting Jewish parents. Their main connection was music. His father was an irascible, rough-hewn engineer who had wanted to be an opera singer, and his mother was a sharp-tongued, anxious, emotional pianist from a refined and musical family. Shteyngart would strive all his life to fulfill his parents’ own thwarted ambition—only instead of relying on the romantic, destabilizing force of music, he chose the more detached and analytic career path of writing.

In love with words and stories, little Igor decided to become a writer at the age of five; his grandmother paid him by the page in slices of hard, yellow Soviet cheese as he wrote his first novel, Lenin and His Magical Goose. “I am writing the novel for my grandmother . . . and I am saying, Grandmother: please love me. It’s a message, both desperate and common, that I will extend to her and to my parents and, later, to a bunch of yeshiva schoolchildren in Queens and, still later, to my several readers around the world.” This passage, representative of Shteyngart’s narrative strategy, is self-mocking and plaintive, funny without trying too hard, and painfully honest.

Indeed, the book’s title comes from the nickname his mother called him: Failurchka, a Russian-English amalgam of love and mockery that set the tone for Shteyngart’s expectations for himself. He would never be the accountant or lawyer his parents wanted him to be. He would never succeed at love or life or writing. He would always come up short, would never grow tall.

Then he became an American, thanks to a deal brokered between Jimmy Carter and Leonid Brezhnev, exchanging American grain for Soviet Jews. The Shteyngart family was able to emigrate in 1979. They settled in Queens, and they changed Igor’s name to Gary so he would suffer fewer beatings in school. In fact, he received plenty of beatings at home at the hands of his father, who loved his son with single-minded devotion, but who also couldn’t seem to stop hitting him for reasons the grown-up Gary guesses at, empathetically, even lovingly; throughout Little Failure, indeed, he imagines himself into the psyches of the people he loves, always forgivingly, always at his own expense. This is one of the book’s major strengths. Shteyngart’s stalwart refusal to cast himself as a victim sets this book apart from the majority of American memoirs, whose authors seem hell-bent on passing judgment on the people who raised them.

Because he was small, clever, and sickly, Shteyngart learned early on that the best, and maybe the only, way to keep from getting beaten up and mocked at school was to make the other kids laugh, to entertain them. He achieved something almost like popularity in elementary school by writing a serial science-fiction novel. Any step toward wider social acceptance was an incredibly welcome breakthrough: Shteyngart was an anxiety-riddled misfit in the ever-delicate social ecosystem of the American adolescent. His social strategy reinforced the lesson he learned in his grandmother’s care: Writing could serve as a way into other worlds and identities, an escape from reality.

In high school, Shteyngart found drugs and alcohol, or they found him, which added another layer of escape. He obsessively, passionately pined for romantic love as well as sex, but he didn’t find either until his sophomore year at Oberlin in 1992. That spring, he fell in love for the first time—with a sexy, brilliant student he calls J.Z.—and enjoyed his first serious long-term relationship. After it ended, after graduation, he came back to New York, settled in Manhattan, and spent another four years yearningly alone until he met his next girlfriend, Pamela, a cold, distant would-be writer who already had a boyfriend. She made Shteyngart feel like a “Big Furry Bitch”; finally, he drunkenly confronted her boyfriend, and put an end to it all.

Throughout these years, alcohol and pot were his constant companions, along with his burning, unfulfilled ambition and unstoppable, antic sense of humor. There was also his mentor and (finally) lifesaver: an older, richer television writer named John, whom Shteyngart alternately hated and needed. To repay John’s kindness, Shteyngart threw tantrums, insulted him, and treated him with derision. (“Well, what do you know? . . . You’re just a television writer. You’ve never written a novel.”) John put up with this, showing Shteyngart unflagging respect and generosity, lending him money, buying him dinner at tony restaurants, reading every draft of his novel, encouraging him, even charming his parents. But finally, when Shteyngart was almost thirty, John gave him an ultimatum: Go into therapy and deal with your drinking and rage and self-sabotage, or you’re on your own.

Shteyngart wisely chose the therapy, which worked. Self-examination led to action. It enabled him to apply to creative-writing programs, to go back to Russia and face his past, and to distance himself, once and for all, from his often needy, manipulative, mean, and controlling parents. Instead of getting an MFA, he sold his first novel. He wooed and won the woman he would eventually marry. He freed himself from the idea of himself as a predetermined failure.

But this transformation does not take place until the book’s final pages. The point of writing this memoir was manifestly not to take a victory lap, to crow about his own accomplishments, to settle old scores, prove points, or grind axes. Little Failure is a painful, painstaking examination of what Gary Shteyngart had to overcome in order to achieve this hard-won, late-blooming, deeply treasured adult success and stability. The panic-inducing memory of what happened in the Chesme Church (which I will not reveal here) becomes, in the end, a sort of metaphor for all of it. By facing and examining and coming to terms with, and getting free of, his past, Gary Shteyngart turned into a Big Winner. And now he has the bravery and the self-knowledge to expose himself.

“On so many occasions in my novels,” he writes, “I have approached a certain truth only to turn away from it, only to point my finger and laugh at it and then scurry back to safety. In this book, I promised myself I would not point the finger. My laughter would be intermittent. There would be no safety.” By this point in the book, the reader understands exactly what fueled Shteyngart’s class-clown urge to point and laugh and flee, as well as how much courage he had to summon to resist that ancient temptation to pursue safety first in writing this memoir.

This rollicking, splayed-out, no-holds-barred account of his life is often unnervingly frank, sometimes shocking—and occasionally disorienting, in a good way. Shteyngart seems to have made a deal with some minor devil (a daredevil?) stipulating that if he exposed every crack and fissure in himself, laid bare every misstep, fuckup, and psychic flaw, his memoir would be a deep and original book. If so, the payoff here was absolutely worth it.

Kate Christensen’s most recent book is Blue Plate Special: An Autobiography of My Appetites (Doubleday, 2013).