In times of transition, clarity can be hard to come by, and a lucid observer is invaluable. Such rare voices can seem, in the hubbub, easy to ignore: It has been almost twenty-five years since Bill McKibben wrote The End of Nature, and yet, rather like the Tank Man of Tiananmen Square, his valiant protest has—so far—failed to halt the juggernaut.

The loss of the particular, private leisure of literary reading seems, arguably, of little importance next to the destruction of our planet. And just as there are those who insist that the ecosystem is perfectly sound, there are many who will contend that literature is not in jeopardy, that while we’re in the process of a logical and inevitable leap from paper books to digital ones, there’s no reason to question the health of our reading nation. In 2011, a staggering 328,259 new books were published in the United States.

And yet. Just as the slow alteration of our environment leads, at first imperceptibly but ultimately at great speed, to unimaginable changes in our planet, so, too, less tangible shifts in human behavior will have, over time, dramatic consequences. Over the last twenty years, we have submitted, often joyfully, to the encroaching mediation of our lives. These developments enable me to look up in one second the number of books published in the United States each year; to identify every unattributed quotation in Muriel Spark’s The Girls of Slender Means; to summon the bibliography of any author who interests me, learn a little about each of her books, and order one within minutes for rapid delivery to my door.

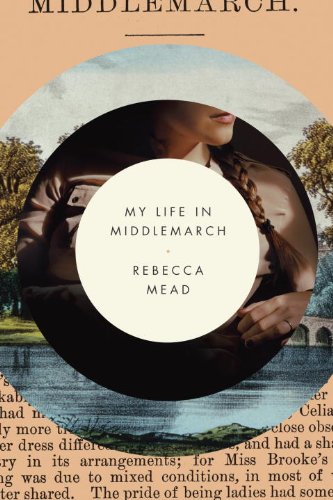

It is nothing short of miraculous. But what’s being lost is precisely private leisure, the unmediated time in which those of us over thirty-five spent almost all of our youth. With it, a type of itchy boredom has evaporated, but so, too, have the unexpected and delectable discoveries born thereof. Without boredom, I would surely never have become a writer. Reading got me through endless car trips and rainy afternoons. Over the course of miserable college summers as a temp, I used the IBM Selectrics to tap out endless single-spaced letters on yellow draft paper to my friends. As Rebecca Mead observes, in her delicious celebration of George Eliot, My Life in Middlemarch, “Writing letters was one of the things there was to do while I was waiting for my life to start.”

Those rambling, often trivial missives represent a type of communication now all but gone from this earth. Arguably, blogs serve this purpose today; but the intimacy of a letter—in dialogue with a particular interlocutor—is not reproducible online. A fluid movement between abstract and concrete, between fiction and fact, between thought and detail—the shaping of a thinking mind, and an unforced articulation of how that mind works—was possible, even inevitable. A gift to the writer, such letters were also a gift to the reader: It’s a particular joy to read a missive written to you, with your predilections and foibles in mind.

An analogous joy, of course, arises from the reading of fiction. There’s a particular exhilaration in the sense that a book—a publicly available book—speaks immediately and directly to you. As Mead notes, “Reading is sometimes thought of as a form of escapism. . . . But a book can also be where one finds oneself; and when a reader is grasped and held by a book, reading does not feel like an escape from life so much as it feels like an urgent, crucial dimension of life itself.”

The dialogue that arises between two people who love the same book is a kind of love affair. And for Mead, Middlemarch is the central novel of her life:

My Middlemarch is not the same as anyone else’s Middlemarch; it is not even the same as my Middlemarch of twenty-five years ago. Sometimes, we find that a book we love has moved another person in the same ways as it has moved ourselves, and one definition of compatibility might be when two people have highlighted the same passages in their editions of a favorite novel. But we each have our own internal version of the book, with lines remembered and resonances felt.

Mead beautifully conveys the excitement of living in a novel, of knowing its characters as if they breathed, of revisiting them over time and seeing them differently. She conveys, too, not at all heavy-handedly, the particular relation one develops with an author whose work one loves. She notes the serendipitous overlaps: Mead, like Eliot, met her beloved husband in her thirties; like Eliot, she rejoices as a mother in her stepchildren; she finds that one inspiration for The Mill on the Floss was her childhood home of Radipole; and so on. She constructs Eliot as eminently lovable, tenderly excusing her youthful priggishness; and although the author was famously homely, Mead is at pains to convey Henry James’s generous impression: “In this vast ugliness resides a most powerful beauty which . . . steals forth and charms the mind, so that you end as I ended, in falling in love with her.” Would that each of us could have, even posthumously, as loving and thoughtful a friend.

Mead, whose lucid prose and intellect are a constant pleasure, moves with wise calm (not unlike Eliot herself) from the biography of Mary Ann Evans to her own experiences, from the significance of various characters in Middlemarch and their relationships to the strange, wispy material legacy of Eliot’s life (one of her homes has been turned into a hotel with slot machines in the lobby; another is now the Coventry Bangladesh Centre, providing “employment advice and training”). There is a meticulous underlying order to the book, structured to mirror Middlemarch itself, but as in a letter, the effect is of spontaneous movement, the particular thrill of following a mind untrammeled.

Just as Rebecca Mead has written a love letter to Middlemarch, Wendy Lesser has penned a love letter to the reading of literature. Why I Read: The Serious Pleasure of Books is similarly impassioned, but differently, and more broadly sprawling. Lesser’s enterprise, in its address, is explicitly intimate—“I have never consciously thought about audience before. . . . But with this book . . . I find myself wondering who you are”—and its aim is to identify the ways in which literature works most profoundly upon us. Its “open-endedness” is key, as is the fact that it “has taken its shape organically.” Lesser, most pleasingly, is in favor of the aleatory: “There are no topics that absolutely had to be covered in this book. There are no essential facts that I needed to convey to you about literature.” Rather, as for Mead, there is a somewhat circuitous, exuberantly digressive progress through Lesser’s literary favorites.

Lesser’s taste is eclectic, her range large. She offers insights into George Orwell and Henning Mankell, Emily Dickinson and Roberto Bolaño, J. R. Ackerley and Shakespeare, Henry James and Isaac Asimov—to name but a few. There is no claim to a comprehensive approach, nor even a sense that what is discussed is of greater importance than what is not: “I may admire Tolstoy as much as I admire Dostoyevsky . . . and yet it is Dostoyevsky who insists on returning again and again to this book.” The effect is rather as if Lesser were writing to a friend about the most fabulous literary party of all time, where she’d been in conversation not with authors but with their works.

There is room for the reader to disagree with Lesser’s opinions (as I must, for example, with her assertion that “the world of Montaigne’s essays . . . can seem airless. . . . It is not an easy place in which to spend time”), and even to be occasionally faintly bored by apparent trivialities (as when she discusses her reading relationship to books versus modern technologies: “I do read, though, on both my iPad and my iPhone. Most of the mysteries I read these days are purchased in digital form. . . . It is annoying that you can’t lend them out or give away these newly finished mysteries”).

But this space, in Lesser’s book, is part of its pleasure, the revival of a form of discourse ever less available to us. Her book—like Mead’s—is thoughtful and intelligent, conversational without being “improving,” and it ultimately encourages us to formulate our own responses, to continue and enlarge the literary conversation.

If Philip Roth’s Mickey Sabbath was a “monk of fucking,” Lesser and Mead are nuns of reading. As a fellow sister in the order, I take particular pleasure in their books. But I’m also aware that nuns are an aging population, and converts ever harder to enlist. My daughter, all of twelve and a voracious reader, lives in a world in which iTunes, Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter all vie pressingly for her time. Pretty Little Liars stands a better chance than Jane Eyre, and facilitates way more conversation with her peers. In Rebecca Mead’s and my own near-simultaneous youths, “books gave us a way to shape ourselves—to form our thoughts and to signal to each other who we were and who we wanted to be.” It’s not exactly that this is no longer true, but that the balance has shifted, and is ever shifting, away from the concentrated leisure, the active effort, of reading and imagining, toward other, more immediately accessible—and more passive—cultural forms.

Letters, and more painfully, their contents, are already largely gone; other literary species are endangered. The landscape changes inexorably, and we can’t know the future. But Mead and Lesser remind us of what riches we have—an interior world as precious as the external one—and of why we don’t want to lose them.

Claire Messud’s most recent novel is The Woman Upstairs (Knopf, 2013).