People in the arts talk about talent all the time: who has it, who discovered the person who had it, its peaks and valleys, and when it has been “lost” or “wasted.” It’s all said as if we know what talent is, when we don’t. It is more than aptitude or being a quick study. It is more than skill, and closer to ease or sparkle in the skill’s application. It somehow forms a trinity with effort and inspiration, but without talent, those two can seem like sad and misguided cul-de-sacs.

But there is also a talent to having talent, and to living with it. Talent can seem like an alien invasion of the self, a kind of parasite that requires its host to do things it might not otherwise do. It’s like the toxoplasma that brainwashes a field mouse to surrender its life to a cat because the feline anatomy is where the parasite is next driven to feed and breed. Cultural history includes many figures who seemed antagonistic to their talent—to resent it, wrestle with it, defy it, even wish to purge or abandon it altogether like Rimbaud. That struggle seems to be a formula for dying young, as if the daemon is fiercer than the mere human, and the only way to destroy it is to kill the vessel, too.

By those measures, Alex Chilton didn’t do too badly by making it to the spring of 2010 at the age of fifty-nine. Those who knew him thirty years earlier wouldn’t have bet on it. If you know Chilton’s work no other way, you’ve probably heard “In the Street,” the teenage hangout anthem that was rerecorded by Cheap Trick to be the theme song to That ’70s Show. But like many avid rock listeners in the 1980s and ’90s, I became an Alex Chilton fan because the musicians I loved were Alex Chilton fans, especially of his early-’70s band Big Star. There would be name-drops in interviews, cover versions, and other references by admirers such as R.E.M., the Cramps, the Bangles, Wilco, Teenage Fanclub, the dB’s, Yo La Tengo, the Flaming Lips, the Dream Syndicate, and Elliott Smith.

If one managed to miss all of that, there was an unmistakable signpost planted atop a high hill, the 1987 song “Alex Chilton” from Pleased to Meet Me by the Replacements. With its zooming pace and its lilting clap-along refrain, it dressed Chilton up in a Superman cape and launched him into orbit: “Children by the millions sing for Alex Chilton when he comes ’round / They sing, ‘I’m in love.’ / ‘What’s that song?’ / ‘I’m in love with that song.’” You couldn’t hear it without immediately wanting to know who the hell Alex Chilton was.

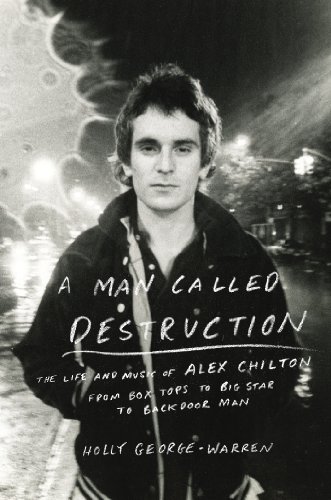

As you can learn from Holly George-Warren’s new biography of Chilton, A Man Called Destruction—as well as previous accounts such as Rob Jovanovic’s 2004 book Big Star, Robert Gordon’s 1995 It Came from Memphis, and Drew DeNicola and Olivia Mori’s recent documentary Big Star: Nothing Can Hurt Me—the bizarre part of all this worship is that, even in its own brief heyday, Big Star as a band hardly existed.

The group seldom toured outside its Memphis home base and even there rarely played live. The blend of hubris and self-deprecation coded in its name (lifted from a local grocery-store chain) and in the title of its first album, #1 Record, extended to the conceit that it could function mainly as a studio band. Its members camped out all hours of day and night in the Ardent Records building in Memphis, precision tooling—and later precision demolishing—gems of rhythm and melody and attitude. Today we’d call its music “power pop,” but that phrase wasn’t in vogue at the time, when the band mainly seemed like an unfashionable throwback to the Beatles and Stones and Byrds, lacking the heaviosity of prog or Zeppelin or the chooglin’ bands popular in the South.

Ardent’s status as a subsidiary of Memphis’s legendary Stax Records was both a blessing and a millstone. Stax was a soul label that didn’t know the rock market, and Ardent’s fortunes were quick to decline. Big Star’s records piled up in warehouses, their routes to the retail outlets blocked by neglect or incompetence or one deal or another that had fallen through. You could read about the music, and once in a blue moon hear it on a radio station, but you couldn’t buy it.

Cofounder Chris Bell, who’d conceived the Big Star sound, had a breakdown and quit after realizing #1 Record’s doom, though not before nearly erasing the master tapes. Chilton, drummer Jody Stephens, and various cronies persisted for two more albums, just as brilliant but ever more shambling and perverse. One of my favorite tracks on Third/Sister Lovers is a funereal ballad that informs its target, “You’re a wasted face / You’re a sad-eyed lie / You’re a holocaust”—before dispersing in disarray.

It was only as scarce copies circulated among musicians and critics and finally made their way to reissue labels, in Britain before America, that the music became widely available. By that point, Bell had died in a car wreck, Chilton had become a kind of wandering punk/oldies/jazz troubadour based in New Orleans, and most of their Memphis associates had moved on to safer lifestyle choices. Eventually, Chilton and Stephens did “reunite” Big Star for shows and tours with their younger acolytes, but Chilton resisted reviving the band’s sound in his newer work, and larger labels continued to be uncooperative in return. He died just before a scheduled Big Star headlining showcase at South by Southwest in Austin, which turned into an impromptu tribute concert instead. It was its own kind of classic no-show for a man who was at once the Hank Williams and the Andy Kaufman of what became indie rock.

But there’s another reason this “invisible man” continues to have a “visible voice,” as the Replacements sang it: Chilton wasn’t striving for rock stardom so much as running away from it. He’d already been famous as a teenager as the gravelly R&B-style singer fronting the Box Tops, whose first and biggest hit, “The Letter” (produced by Stax songwriter Dan Penn), remains an oldies staple. He’d spent the late ’60s on tour, appearing on American Bandstand and hanging out with the Beach Boys. The “boy interrupted” backstory to his career may help explain why his later styles were forever out of touch with the subcultures of the day.

Like other teen idols, the Box Tops–era Chilton soon began to chafe against being the puppet of producers rather than a creative power of his own. This condition was probably more acute in his case because, as one of the livelier sections of George-Warren’s thorough but slow-paced account of Chilton’s life spells out, he had grown up in bohemia. His father was a salesman but also a proficient jazz musician, and his mother ran an art gallery out of their house, where touring musicians and local artists partied heavily at all hours. The photographer William Eggleston, whose images graced the covers of Big Star’s Radio City and other Chilton projects, was a family friend.

So where later bandmates like Bell were affluent suburban youths dreaming of jets and stadiums, Chilton’s urges went other ways. Rock critics’ ears still perked up when they heard his name, and Big Star did get reviews in Rolling Stone and Billboard when another obscure band might have been ignored. If he’d been willing to work his reputation harder, the distribution stalemate probably could have been overcome. But he preferred to catch up on the wayward youth he’d missed as a genuine big star, a band name that’s doubly ironic and cursed if considered that way.

Even with that group safely consigned to bargain bins and whispers, Chilton kept sabotaging gigs, recordings, and expectations, often via booze and pills, it’s true, but also with more imaginative dodges. You can almost see his collaborators shaking their heads as they’re quoted about his facility as a player (“the Thelonious Monk of rhythm guitar,” as Tom Waits once called him), singer, producer, and musical encyclopedia, and then describe his decision to play backup in performance-art rockabilly-noise band Tav Falco’s Panther Burns instead. Take that, talent.

Yet Chilton’s story doesn’t read mainly as one of missed opportunity. Yes, he could have dedicated himself to producing pop masterpieces, but he probably changed music and culture just as effectively with his elusiveness; his messes gave permission to his emulators not to fuss so much with loose ends. And no matter how pissed and pissy he got, people are more inclined to talk about his charm and magnetism. Almost no one seems to regret any encounters with Chilton, however fickle he could be with friends and lovers alike, and that’s a credit to any life.

As I worked my way through the book’s steady procession of neutrally narrated anecdotes of recording-session anarchy, lazy days and debauched nights, broken friendships and bruising romances, off-the-cuff performances and hastily assembled bands, I kept being startled to realize how young Chilton still was, chapter by chapter and event by event. His considerable excesses aren’t uncommon among musicians in their twenties and early thirties, and they vastly abated after that. There’s a tale of substance abuse here, yes, but the deeper sources of his agitation and ambivalence pose more of a problem of ambience: of a family haunted by the early death of a beloved older sibling, for instance, and Chilton’s never-quite-explained animus toward his parents; and even more so about Memphis, Chilton’s crucible and his nemesis, with its buoyant musical swamp gas and its miasma of social-historical divisions and tragedy, all of which seemed to bubble and permeate particularly into Big Star’s fate.

But Chilton’s story is also a mystery about whatever drives a handful of artists to be great at the expense of being good, to gamble double or nothing on the long odds. That may be talent’s most agile rival spirit, for which we have few other terms than the dumb old romantic one of genius. To paraphrase an equally disobedient (but luckier) artist, Chilton lived outside the law by being honest, and we’ll likely keep talking about his putative failure long after the successes of stars who tended their talents more diligently fade from memory. “Everybody goes as far as they can,” Chilton sang in “Holocaust,” then added, direct from the B side of perfect sense: “They don’t just care.”

Carl Wilson is the Toronto-based author of Let’s Talk About Love: A Journey to the End of Taste, which was just reissued in a new expanded edition by Bloomsbury.