As a young literatus in training, I got myself early and often to the Lion’s Head, a legendary and now-extinct writers’ bar on Sheridan Square. Lined with the framed covers of books by its denizens, it offered an atmosphere of boozy bonhomie and the opportunity for literary stargazing of a special sort. (Hey, I’m urinating right next to Fred Exley!) And it didn’t take long before I was told that gin mill’s trademark anecdote: A nonscribbling civilian drops into the Lion’s Head for a couple of beers. After taking in the scene for a while, he remarks to the guy on the barstool next to him, “There sure are a lot of writers here with drinking problems.”This elicits the swift reply: “Wrong. There are a lot of drinkers here with writing problems.”

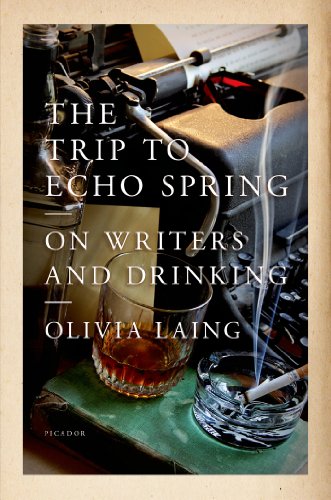

The same conundrum informs Olivia Laing’s heartfelt and melancholy alcoholic travelogue: Why, in America especially, are the production of literature and the consumption of destructive quantities of alcohol so intimately intertwined? Which came first, the bottle or the typewriter? While this condition has abated quite a bit in our more abstemious time (it’s been many years since I’ve seen anyone come back loaded from a publishing lunch), for much of the twentieth century, literary distinction and alcoholism were strongly linked. An oft-cited fact is that five of the first six American Nobel Prize winners—Lewis, O’Neill, Faulkner, Hemingway, and Steinbeck—were alcoholics, and the list of other notable writers who suffered from the disease would more or less fill the allotted word count of this review. Laing, a British editor and critic, battens on to six of these sad, brilliant cases, all men, in an attempt to solve, or at least shed light on, the paradox that their desolate and haunted lives yielded “some of the most beautiful writing this world has ever seen.” Tennessee Williams, John Cheever, Raymond Carver, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Berryman—ransacked souls all who drank like fish and wrote like fallen angels.

Laing’s method of investigation is to undertake what’s called in AA-speak a “geographical,” a meandering journey, mostly by train, to the significant loci in these writers’ lives, in a gamble that the spirits of place might offer deeper insights than the usual critical and biographical approaches. The motives for her transcontinental travels are a bit fuzzy and abstract (“I wanted time to think, and what I wanted to think about was alcohol,” she asserts in her introduction, and she later alludes to a period of domestic chaos when her mother lived with an alcoholic partner), but the strength of her writing and the shrewdness of her surmises more than justify the exercise. Laing has the ability to penetrate the barriers of denial and sheer fraudulence that all alcoholics, and writers in particular, throw up against others, and especially against themselves. At times she achieves a certain level of soul travel or metempsychosis in taking us into the dark and twisted interior spaces where psychic trauma and creative inspiration struggle for mastery.

A lot of this territory was covered in Tom Dardis’s 1989 The Thirsty Muse: Alcohol and the American Writer. Dardis is almost forensic in method and prosecutorial in intent, doggedly determined to prove that the works of Faulkner, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, and O’Neill declined in exact proportion to the doleful progress of their disease. He is the critic as stern AA sponsor, and while he makes his case with largely irrefutable detail, he holds himself at a certain distance from his subjects’ inner torment and chaos. In contrast, The Trip to Echo Spring is the work of an empath capable of bold leaps of intuition and imagination into the minds and souls of her chosen writers. Sometimes physical leaps: She even takes a charter boat to swim in the exact spot in the Gulf of Mexico where Tennessee Williams wanted his ashes to be scattered.

Those minds and souls are not, by and large, pretty places to be, yet the travels to what Laing rightly calls “the more difficult regions of human experience and knowledge” are, in varying degrees, piercing, angering, revelatory, profoundly depressing, and shot through with moments of near-spiritual illumination. The book’s title derives from a line in Cat on a Hot Tin Roof when Brick grabs his crutch (symbol alert!) and tells Big Daddy, “I’m takin’ a little short trip to Echo Spring”—a liquor cabinet filled with a brand of bourbon by that name. Like Brick, Williams himself took that (by no means short) trip as a way of tamping down sexual anxiety and also shyness—two prime triggers for alcoholics. John Berryman, the book’s least sympathetic figure, a literary and sexual braggart who could write a novel titled Recovery while utterly failing to put its insights into practice, drank (and drank and drank and drank and then drank some more) to self-medicate the trauma of his father’s suicide and a miserable prep-school adolescence. Fitzgerald and Hemingway are the Denial Twins of our literature; the former deluded himself that alcohol was essential to his literary inspiration, while the latter deluded himself that he had everything, his drinking and his depression and his multiple psychic and physical wounds, under stoic and manly control. Although Laing is well versed in the literature of alcoholism, knowing far more about the medical and psychological nature of the disease than her subjects ever could have, she successfully resists the temptations of the pat casebook explanation and the attitude of in-the-know superiority.

She is especially good on the walking paradox that was John Cheever. His Journals (published in 1991) offer the most profoundly mixed reading experience I’ve ever had—sordid instances of sexual abasement and alcoholic excess and poisonous animus directed at his wife and family, all rendered in the most exquisite prose imaginable. Cheever’s surface image as the winsome, Waspy squire of suburbia masked profound social and financial anxieties and resentments and a hidden hyperactive homosexual life conducted in the furtive shadows. The AA commonplace “You’re only as sick as your secrets” could be the motto on the Cheever family crest. Like so many alcoholics, Cheever had the perversely impressive ability to deny the unpleasant facts of his own behavior; Laing cites instances where Cheever waxes peevish about his wife’s conjugal coldness, failing to grasp that sleeping with her sodden husband could hold no appeal whatsoever. And yet, in 1973, after twenty-eight days at the Smithers Center in New York City, “by some miracle” Cheever emerges from his slough of self-pity and morbid narcissism never to drink again—a resurrection symbolically repurposed in his one fully achieved novel, Falconer. Giving the lie to Dardis’s diagnosis, however, Laing has the wit to realize that many of Cheever’s greatest stories were written at the flood tide of his alcoholic intake. Here and elsewhere, she demonstrates a fine Keatsian capacity to be “in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact & reason”—fact and reason not being of much use in a consideration of John Cheever.

The same goes for the one other of Laing’s subjects who managed to stop drinking in the final years of his life, Raymond Carver, Cheever’s close friend and boozing companion. (The book opens with a scene of the two men outside a state liquor store in Iowa City at 9 AM, eager for their twice-weekly eye-opener of a half gallon of scotch. As Carver confessed, “He and I did nothing but drink.”) Carver’s life rivaled and perhaps even exceeded Cheever’s in alcoholic abjectness, if not in louche sexual content; his was the blue-collar version, replete with unpaid bills and demeaning employment and the near-total absence of glamour. The final stop in Laing’s pilgrimage (the precisely correct word) is Port Angeles, at land’s end of the Pacific Northwest, where Carver finally completed his climb out of the wreckage of a life of privation and physical and moral squalor. When we at last are faced with our irreconcilability, our helplessness to control or even understand our dreams and desires, we can have recourse to two forms of surrender: a giving up, which Berryman and Hemingway chose in its most extreme form, suicide; or a giving over, Carver’s happy choice, to the cosmic gamble that is faith. Laing visits two sacred places in Carver mythology, Morse Creek, a holy spot of peace where he fished for steelhead in the years before lung cancer killed him; and the Ocean View Cemetery, where he is buried. Next to the grave is a notebook where visitors leave messages, including many from people struggling with alcoholism for whom Carver is a saint of sobriety. It is no accident that the stories of Carver’s final years are stunning in their spiritual amplitude and their intimate association with mystery. Laing’s epiphany—“In the end, recovery depends on faith, of one kind or another”—and her evocation of the healing capacities of literature, are eloquent and earned. Higher powers are where you find them.

The workings of grace are impossible to predict or even to understand—that’s why they call it grace. Until the geneticists, neuroscientists, and evolutionary biologists complete their Sisyphean task of explaining ourselves to ourselves (and thus rendering us completely uninteresting), we will have to dwell in its inexplicable presences and absences. So let’s give the final word to Edmund Wilson, from his great essay on human frailty and strength and the tangled roots of artistic creativity, “The Wound and the Bow”: “The victim of a malodorous disease which renders him abhorrent to society and periodically degrades him is also the master of a superhuman art which everybody has to respect and which the normal man finds he needs.” Olivia Laing doesn’t quote those words, but her fine book manages to lend them new and highly specific meaning.

Gerald Howard is an editor at Doubleday.