German by the grace of Goethe: A century ago, this formulation served, for many German Jews, as a kind of motto. Never mind that, like so many progressive reforms in Germany, full emancipation of the Jews had been a top-down affair, pushed through by Otto von Bismarck without much pressure from below. The idea was that the Jews had the liberal tradition in German culture—which Goethe best embodied—to thank for their enfranchisement. And this faith was bolstered by the allied sense that Jews had acquired their Germanness through their mastery of canonical German culture—again best represented by Goethe.

What’s clear, in any case, is that more than a few of the six hundred thousand Jews living in Germany before the First World War felt themselves to be German and Jewish. That was the case even if many German Jews did most of their socializing with other Jews. Hence the name of the largest Jewish organization in Germany at the time: the Central Association of German Citizens of the Jewish Faith.

The balancing act of a dual identity remained quite tricky for German Jews of all persuasions: Reform, modern Orthodox, cosmopolitan, Zionist, etc. In one widely discussed argument from 1912, Moritz Goldstein, a young scholar of German literature with Zionist sympathies, argued that German Jews needed to tap into the resource of their Germanness in order to thrive spiritually. This was no easy task, Goldstein conceded; being both German and Jewish proved especially fraught—enough to leave them psychically stunted. If, on the other hand, the Jews were to turn away from German culture—which, adding a further wrinkle, Goldstein declared to be “also Jewish culture”—they would suffer more damage: A “piece of their heart would be left hanging” on Germany.

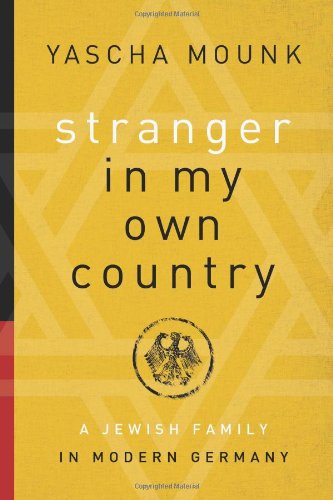

How do things stand with German Jews a century later? In Stranger in My Own Country, Yascha Mounk, another young German-Jewish academic, who now lives in New York City, gives an artful and thoughtful answer. The thirtysomething grandchild of Holocaust survivors, Mounk was the son of a musically gifted single mother who moved to Germany, from Poland, in the late 1960s, when Poland’s leaders were pressuring many Polish Jews to leave. She felt uneasy about settling there, but the professional opportunities were good. Through marriage, she gained German citizenship, and so she stayed on.

In 1990, when the German soccer team won the World Cup title, Mounk’s joy was boundless. But his reflexive identification with Germany—his ability “to think of” himself “as a German” in the folkways of German nationalism—steadily eroded as the awkward experiences, some ugly and some farcical, piled up. When he was in middle school, he witnessed a drunken opera singer berating his mother, at that point a rising conductor, in an anti-Semitic outburst: “You are a Jew. I am a German. You shouldn’t be telling me anything.” He learned soon thereafter that his mother had received anti-Semitic hate mail. Around the same time, a middle-school teacher asked him to state his confessional affiliation, and when he replied “Jewish,” his classmates laughed; unable to get their heads around the idea that Jews still lived in Germany, they assumed that he was joking. Later on, high school students started to bully Mounk, on the preposterous grounds that they felt aggrieved by the chastising presence of Jews in the German media. They pinned him down and came close to shaving his head before he managed to escape.

Meanwhile, some of Mounk’s other peers fetishize his Jewish background; it was their motivation for wanting to befriend him. Some felt the need to demonstrate that the past is the past and defiantly told anti-Semitic jokes in his presence. “The Holocaust happened sixty years ago,” one of them announced. “We should tell jokes about Jews again!” Other people felt constrained: Mounk records an episode in which one friend abruptly stopped criticizing Woody Allen when he saw Mounk approaching. More than “violence or hatred,” Mounk writes, overbearing “benevolence” gave him the sense that he “would never be a German.”

Mounk’s personal anecdotes do a lot to make his mind-set understandable, but he also deals with the big picture. Indeed, the best feature of his fine book is how it interweaves micro and macro levels of discussion—in the manner of Covering (2006), Kenji Yoshino’s excellent memoir-cum–civil rights treatise about Asian-immigrant and gay experience in the United States. Mounk likewise tracks all phases of German-Jewish relations since the Second World War, situating them in the even larger context of Germany’s struggle to come to terms with its past. He does this, moreover, in graceful prose, which helps to showcase his gift for disentangling paradoxes in original ways. Stranger in My Own Country is especially astute in laying out how the philo-Semitism and the left-wing anti-Semitism that emerged in Germany in the 1970s could ultimately stem from the same force: the desire to overcome a sense of historical guilt.

Sometimes Mounk stretches his evidence a bit, as when he cites a surfeit of interest in the erratic fin de siècle Zionist philosopher Theodor Lessing as an example of the excesses of today’s German philo-Semitism. Contrary to what Mounk asserts, “new editions of Lessing’s works” have hardly been “flooding the German book market,” nor have “historians and literary scholars” published “new works about him in droves.” You can count those studies on the fingers of both hands.

But despite such oversights, the virtues of Mounk’s farewell letter to Germany far outweigh its flaws. With the problem of the Nazi past looming large, and the grace of Goethe long gone, one hopes that Mounk will keep his eyes trained on the deep paradoxes informing German-Jewish lives, even if he no longer sees himself as a German Jew.

Paul Reitter is the director of the Humanities Institute at Ohio State University.