There is a particular form of low-lying corruption that you learn to live with if you belong to certain kinds of cities. They are sprawling, chaotic, overpopulated places whose residents claim what space they can around tentacles of unplanned roads and a pandemonium of traffic. Their various nuclei are government buildings that comprise long corridors and annexes that are navigated like a maze; systems that take you back and forth from one point to another, one counter to the next, one officer to another, who may or may not sign your paper before telling you to go elsewhere. He gives you a name, someone he knows.

These cities—like Lagos or Cairo—run slickly on an emergent logic of their own. The traffic, to those who live with it, feels more cohesive with its lack of lights and lines and order, with the one-way street that on some days becomes two, and the officer who will let you cut corners and park where you can’t. At the local traffic department, your file of fines is retrieved within seconds from pyramidal piles of paper. It is also, just as quickly and for a pittance, put away. To those of us who belong to these places, we learn, early on, to contribute to this codified disarray—to feed the hidden veins that make it run—if we are to survive and construct lives ourselves. They are tips, to our minds, not bribes.

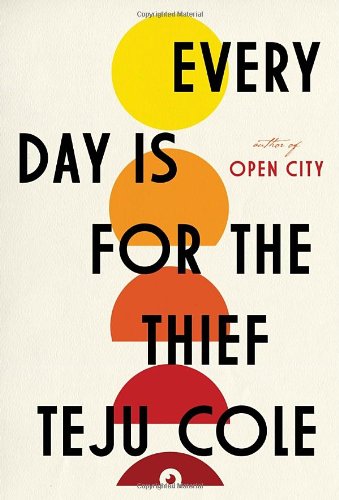

To the stranger, the reality is stark; these cities can feel overwhelming, mystifying, and unscrupulous, even at their embassies abroad. Teju Cole’s new old novella–turned-novel, Every Day Is for the Thief, first published by Nigeria’s Cassava Republic Pressin 2007 and just reissued by Random House, opens at the Nigerian consulate in New York—a decrepit place, noisy, filled with people jostling, pacing, begging for an exception to the rule: “One man begs audibly when he is told to come back at three to pick up his passport: Abdul, I have a flight at five, please now. I’ve got to get back to Boston, please, can anything be done?” They talk, they negotiate, wheedling unfolds. Abdul, eventually, offers that he will “see what can be done.” You know, somehow, that something will be done.

The narrator in Cole’s book is a young Nigerian American, renewing his passport ahead of a planned trip home. He hasn’t been back in fifteen years. Officially, the renewal costs eighty-five dollars (money orders only) and takes one week. Unofficially, it takes that same week but will cost you an “expediting” fee of an additional fifty-five dollars. For this, we learn, you will receive no receipt. We understand within these first few pages that our narrator has either an otherworldly naïveté or perhaps exaggerated piousness—he will balk at the “casual complicity” that he will encounter on his journey, beginning here. Of the expediting fee, he writes:

It is what I have dreaded: a direct run-in with graft. I have mentally rehearsed a reaction for a possible encounter with such corruption at the airport in Lagos. But to walk in off a New York street and face a brazen demand for a bribe: It is a shock I am ill-prepared for.

He conveys further distress at the sign by the elevators on his way out, which reads: “Help us fight corruption. If any employee of the Consulate asks you for a bribe or tip, please let us know.” There is no phone number to ring, no e-mail to write into—you can only complain to Abdul. “It is a farce, given a sophisticated—‘no cash please’—sheen.”

At this consulate, a place that might as well be in one of the aforementioned cities, the general tone and theme of the slim book is laid out. Our unnamed narrator will spend his next few weeks meandering around Lagos, where these encounters with “graft” will be repeatedly recounted. At the airport upon arrival, an official asks, “Ki le mu wa fun wa? What have you brought me for Christmas? Because you know, they spend dollars in New York.” Amid a traffic jam driving home from there, “Aunty Folake explains what is going on. Policemen routinely stop drivers of commercial vehicles at this spot to demand a bribe. The officer being told off has drifted too close into his colleague’s domain. Such clustering is bad for business: drivers get angry if they are charged twice. All this takes place under a billboard that reads ‘Corruption is Illegal: Do Not Give or Accept Bribes.’”

Against this backdrop that feels, perhaps too often, too overtly, like the foreground to his story, our narrator persists in wandering the city. He seeks out Amina, “of a long-ago truancy,” one of his “few sweet memories of the city”—those wistful kinds that stay seared in our minds. He goes to a museum, a jazz shop, a conservatory. Our narrator is principally searching for something that might offer him a sense of hopefulness and possibility. A woman on a bus reading Michael Ondaatje offers a glimmer of it. He finds mostly bewilderment. At the museum, “the whole enterprise is clotted with a weird reticence. It is clear no one cares about the artifacts. There are such gaps in the collection that one can only imagine that there has been a recent plunder. . . . The West had sharpened my appetite for ancient African art. And Lagos is proving a crushing disappointment.” At last at a bookstore, with its “outstanding” presentation, “as well as many a Western bookshop,” he finds “that moving spot of sun” he has sought.

The book is in part a story about Lagos—a journey that offers a vivid, if cursory, entrée into a city that twenty-one million people today call home; the place, he notes, where e-mail inheritance scams (“419’s”) were conceived. The narrator has become something of a stranger to the city he grew up in, and navigates its streets and markets in much the same way a foreigner might (“One goes to the market to participate in the world. As with all things that concern the world, being in the market requires caution”); in this sense, the book seems suited for a preparing traveler—one who hasn’t yet experienced cities like these, who is as “ill-prepared” as the writer seems to be. And yet, since we often cease to see what we are steeped in—the world all around us—Every Day Is for the Thief offers those of us who live in these places a welcome moment of pause, reflection.

At its best, when he makes the connection with the person who once lived there—the one who wouldn’t detail, with staggering surprise, his many encounters with bribery and corruption—it is also a lyrically told story about memory, and how we become estranged from a place to which we once belonged, and even from the person we once were. Of his aunt’s house, which seems larger than he remembers—its hallways wider, its doorways higher—he writes: “The house, of course, is unchanged. It is smaller only in memory, memory and the intervening years, many I have spent in cramped English flats and American apartments, limitations I have endured like a prince in exile. Now, in the cool interior of this great house in Africa, proper size is restored.”

In some ways, the real value of this book is in the glimpse we get of the writer that Cole would come to be, the clear beginnings of the more patient—and more satisfying—narrative of Open City (2011). In that book, he skillfully slowed down the pace and plot that we had come to expect from “the novel,” and drew out a story through a detailed, ruminative, and sophisticated retelling of the everyday, exploring New York in the way one imagines he tried to do with Lagos. This newly published old book begins narrating in that same way, wandering and reflective, but its chapters, its vignettes, its meanderings, fall short. At one point our narrator speaks of the stories he has access to in Lagos, the many he hears as visitors pass through his family house. He speaks of those stories, but hardly shares them. In this sense, perhaps this book is a prelude to his forthcoming nonfiction release on Lagos, Small Fates—a book that one hopes will take its time in the way Open City did, and take us deeper into the Lagos we are offered evocative glimmers of here.

The 176 pages of Every Day Is for the Thief are interspersed with unremarkable snapshots that the eye skips, but that are revealing, perhaps, precisely for that reason; they capture the quotidian, which is swallowed and lost amid cities like these. Of one moment with his camera, an instant that eloquently speaks to his homecoming, and of which—in its reflection and description—one wishes the book had offered more, he writes:

I want to take the little camera out of my pocket and capture the scene. But I am afraid. Afraid that the carpenters, rapt in their meditative task, will look up at me; afraid that I will bind to film what is intended only for the memory, what is meant only for a sidelong glance followed by forgetting. A tall man in a sky-blue cap rhythmically moves his arms back and forth over a butter-colored plank. His arms are lean and black, and he has one eye closed as he works. The shavings fall in a nest about his feet. He is ankle-deep in that soft-wood-stuff which, I suddenly remember, was so fascinating to me when I was a child of seven or eight. I remember the carpenter who made our furniture, the pile of shavings in his shop, and the sweet, oily fragrance they emanated.

Our narrator never revisits the places one would expect him to: his old school, his childhood haunts, his father’s grave. The city he hoped to find doesn’t exist, and he seems unable to reconcile himself to the one that does. Cole’s is the familiar story of memory and association—the chasms that exist between what was, what is, and what we hoped might be.

Yasmine El Rashidi is a contributing editor of Bidoun and the author of The Battle for Egypt: Dispatches from the Revolution (New York Review Books, 2011).