Some years ago, when my first child was finally old enough to sit through a book that (a) was not made of cardboard and (b) had more than four words on a page, I raided the bookshelves of my childhood bedroom with glee. Narrative, at last! All my old favorites were there—the Wizard of Oz books, The Adventures of Pippi Longstocking, The Tale of Peter Rabbit, In the Night Kitchen. I loaded them into a bag and brought them home, and we started right in. Among the spoils was a picture book that had faded from my memory over the years, though its much-dog-eared pages were evidence of the central role it had played in my early reading life. The book, Bread and Jam for Frances, by Russell Hoban, is part of a sweet, funny collection about a badger family whose elder child, Frances, learns a valuable life lesson in each story. Over the course of the series, Frances acquires a baby sister, outwits a dishonest friend, and learns how to fall asleep by herself in spite of noises, scary cracks in the ceiling, and other nighttime horrors. In Bread and Jam for Frances, our furry protagonist rejects her mother’s cooking in favor of the titular meal for a long stretch of days, until she finally breaks down in tears at the dinner table one night and begs for some of the spaghetti and meatballs the rest of the family is eating, having realized that variety is—well, you know—the spice of life.

Lying in bed with my son, reading for the first time in roughly thirty years about all the meals Frances passes over, and then, on the book’s final page, about the elaborate lunch she brings to school as she enters a new era of gustatory delight, I was every bit as overcome as Proust’s narrator with his madeleine:

“Well,” said Frances, laying a paper doily on her desk and setting a tiny vase of violets in the middle of it, “let me see.” She arranged her lunch on the doily.

“I have a thermos bottle with cream of tomato soup,” she said.

“And a lobster-salad sandwich on thin slices of white bread.

“I have celery, carrot sticks, and black olives, and a little cardboard shaker of salt for the celery.

“And two plums and a tiny basket of cherries.

“And vanilla pudding with chocolate sprinkles and a spoon to eat it with.”

“That’s a good lunch,” said Albert. . . . “I think eating is nice.”

“So do I,” said Frances, and she made the lobster-salad sandwich, the celery, the carrot sticks, and the olives come out even.

As I spoke each course out loud, I found I knew what was coming next. That lunch, made all the more dear by its inclusion of a childhood ritual I frequently enacted—trying to control the world by making things “come out even” bite by bite—had been dormant in my memory for decades. Once I recovered it, I might as well have been four years old again myself.

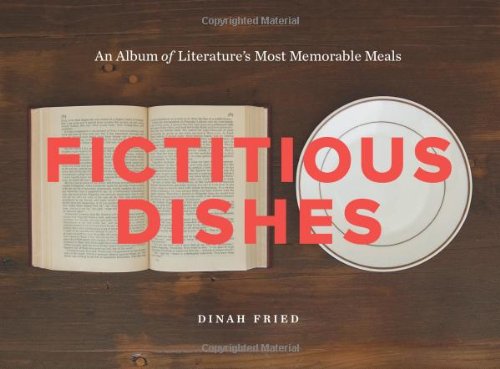

My son has grown beyond Frances these days (though I have another one waiting in the wings who’s a gourmet to boot, and I suspect the book will be back in rotation soon), so I was freshly unprepared, though just as astonished, to encounter that marvelous lunch once again in Dinah Fried’s deeply affecting book Fictitious Dishes: An Album of Literature’s Most Memorable Meals (Harper Design, $20). It appears there not only in writing but in full photographic glory, resplendent as it absolutely must be with its miniature vase of flowers, its pair of plums, and its chocolate sprinkles all accounted for, conjured into being through memory and magic. The precision and ceremony that have gone into it are evident, and so is the affection. The combined effect of these three forces is powerful.

In fact, as I made my way through Fictitious Dishes—moving from The Catcher in the Rye (cheese sandwich, malted milk, shadowy Formica countertop), to Lolita (gin-and-pineapple-juice cocktail, blown dandelion achingly evocative of aging and loss), to A Confederacy of Dunces (hot dog, obviously), to One Hundred Years of Solitude (a beautiful pile of loamy earth, full of secrets)—I had to keep putting the book aside; it was too rich to take in in one sitting. All those lovingly constructed lives, some of which I know better than others, captured in one small volume, plate by plate, add up to nothing less than a catalogue of humanity. Where else are we going to find Humbert Humbert, Heidi, and Gregor Samsa between the same covers?

Fried has pulled off a minor miracle in making a book of artfully photographed pretend meals that never trades in cutesiness or pretentiousness. The children’s classic Blueberries for Sal sits comfortably alongside Madame Bovary, Valley of the Dolls, Gravity’s Rainbow, The Namesake, and Heartburn (and how I wish Nora Ephron were around to see this book). The adorable pail of blueberries, stalwart and bright against a sun-splashed ground of greenery and little flowers, comes from a tale in which children are separated from their mothers but everything turns out just fine in the end. The image is saved from preciousness by the meal on the next page, the chicken dinner made by Calpurnia, Atticus Finch’s housekeeper in To Kill a Mockingbird. The bird, a present to Atticus from Tom Robinson’s father in spite of his son’s conviction, is a thank-you from a man who knows things usually don’t turn out just fine but appreciates it when someone comes along who at least tries to steer things in the right direction.

Fried never says how she chose the books for inclusion, but even though I’m sure we all could cite a few memorable dishes that didn’t make the cut—I’d put a few from Laurie Colwin’s underappreciated novels on the list just for starters—I can’t think of a single argument against any of the ones that do make an appearance. Each meal, accompanied by the passage that describes it and a few points of trivia about either the food or the book it’s from, is a small still life, in the true sense of that phrase, and she has re-created them faithfully, which seems like the only way to do it. One of the great pleasures of rereading any book is finding it to be precisely the same as it was the last time we read it (even if our understanding of it isn’t), and that goes for pictures as well as for words. When faced with re-creating the iconic meal of spaghetti and beans that Hemingway’s Nick makes over an open fire in “Big Two-Hearted River,” you don’t want to be the person who decides it might be fun to update it by substituting black beans for baked. Wisely, Fried gives us Nick’s dinner exactly as we’ve always imagined it—cheap noodles and beans on a tin plate, metal spoon, mug of coffee, all settled at the base of a tree on a patch of ground strewn with sticks and dry pine needles. Heat almost seems to rise off the earthy page. It’s simple and somehow beautiful, but most important, it’s right.

Fictitious Dishes is not a sentimental book, but it’s full of feeling. Every page produces a sense of longing for something—the food pictured, the ability to relive the experience of first reading the book from which it came, or the time in which we did. This not-unpleasant wistfulness is made explicit in the passage Fried quotes from The Bell Jar, spoken by Sylvia Plath’s stand-in, Esther, which accompanies a sumptuous photo of an avocado half stuffed with crabmeat salad.

Avocados are my favorite fruit. Every Sunday my grandfather used to bring me an avocado pear hidden at the bottom of his briefcase under six soiled shirts and the Sunday comics. He taught me how to eat avocados by melting grape jelly and French dressing together in a saucepan and filling the cup of the pear with the garnet sauce. I felt homesick for that sauce. The crabmeat tasted bland in comparison.

Is there anything more human than the desire to eat the things that remind us not just of who we are but to whom we’re connected? And to feed these things to others? Sometimes the food that comes later, as Esther knows, is far worse than second best—and in her case, as Fried tells us in a note, the crabmeat salad that disappointed her also gave her a nasty case of food poisoning. But while Fried is too respectful a reader to reinvent Esther’s meal—fate, even fictitious fate, is fate, after all—if you look closely at the photo you’ll see a small dish of French dressing off to one side, over near the fork, wielding its talismanic power against the ravages of time and illness, just like her book.

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).