If I chose to look at my life through a particularly self-critical lens, my personal narrative would boil down to the story of a woman who spent her entire adulthood trying to get good at something, anything. Beginning in my twenties and with no noticeable talent besides writing, I took classes in a string of leisure-time activities that I hoped would turn into something to love. I have no natural grace, but I tried clogging, then folk dancing, then swing dancing, then tap. I’m not especially artistic, but I took pottery classes and quilting classes. I tried learning Spanish, I tried learning Italian, and I got nowhere with either. And even though I’ve never been especially musical—something made painfully clear during six years of piano lessons as a child—I tried, on and off, starting on my thirtieth birthday, to learn how to play the cello.

In this long, sorry litany, the thing that probably bugs me the most is my failure with the cello. When I started, I already felt too old, as if I had missed my chance ever to get good at it. (In a way I was right; studies show that truly proficient string musicians should start lessons before age seven.) But sometimes I would play a note, or even a whole phrase, with true resonance, and I have to admit it was thrilling. For a while that occasional thrill was enough, sustaining me through the babyish melodies I was given to play, melodies that were so embarrassing I would only practice behind closed doors. I got better, but slowly, and when I was pregnant with my second child and my belly got in the way of the bowing, I quit.

I tried again when I turned fifty, shortly after moving to New York. I turned to Craigslist to track down a cello teacher and found Laura, a sparkly student from Columbia going for a joint degree at Juilliard. Laura came to my apartment once a week and encouraged me as though I were a child, right down to the gold stars. Back to “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” for me, back to the embarrassment of being overheard—but once again I got better, slowly.

Two years in, I read a New York Times Magazine article about a rural doctor in Pennsylvania who learned the cello at age fifty by playing nothing but one piece again and again, the 107 notes of Bach’s Suite no. 5 in C Minor Sarabande. “I am not looking for skills and information,” he told the Times reporter Lisa Belkin about his midlife musical goals. “I want insight, understanding.” I asked Laura if I could do the same thing: learn the Sarabande and stick to that single piece in search of insight and understanding. Laura was game—she was generally game for anything—but I’d miscalculated. In the end, I didn’t stick with lessons long enough even to learn the 107 notes.

What undid me? Two things, if I remember right. The first was cello maintenance, and the second was taking the thing out in public. After five years in an overheated bedroom in our New York apartment, my cello developed a major crack and had to be repaired. The closest luthier shop was near Lincoln Center, but I felt shy about getting it there; I didn’t want to be seen in the subway carrying a cello, worried that folks might mistake me for a person who actually, you know, played. I made my husband drive me down Broadway to the repair shop and wait in the car to drive me back home. And when the luthier told me he would need to replace the whole backboard at a cost of several hundred dollars, that was more than I was willing to invest. I took the cello home and gave it away, unfixed, to my sister-in-law’s friend, a onetime cellist who longed for an instrument of her own so she could accompany her younger son at Suzuki.

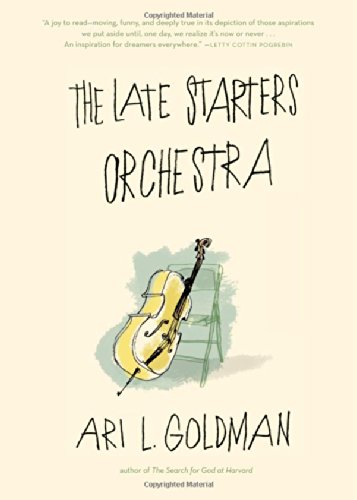

Ari L. Goldman is made of sterner stuff: Neither the expense of repair nor the New York City transit system could dissuade him. He began playing the cello in his twenties, and basically abandoned it to raise a family and pursue a career as a reporter for the New York Times. But when his youngest child started cello lessons, he decided to return to the instrument. When he took his old cello out of storage and brought it to the repair shop—probably the same one I went to, since it turns out Goldman lives in my neighborhood—he was told it would cost $1,500 to bring it up to snuff. Rather than buy a new one, he writes in The Late Starters Orchestra, his charming memoir about learning the cello again in late middle age, he chose to stick with his old cello because it connected him to his first, beloved teacher. He bit the bullet and shelled out the $1,500.

The misapprehensions of others didn’t bother him, either. He found himself schlepping the thing on his back as he took public transit to rehearsals, but he never really worried that people might mistake him for a real musician. In fact, when a young woman on a crosstown bus commiserated over how hard his life must be, playing for a Broadway musical at the matinee and then again at the evening show, he merely smiled and said, “It’s okay. I’m used to this.”

This resilience is the difference between Goldman and me—and the reason that he thrived as a midlife learner and wrote a book describing his experience, and why I sit on the sidelines and can only write the review.

The focus of the memoir is Goldman’s decision, at the age of fifty-nine, to get good enough at the cello to be able to perform for his friends at his sixtieth-birthday party. He took many steps toward that goal—summer trips to northern England and to Maine for total-immersion music camps, a string of private lessons with several teachers (including, much to my delight, my own former instructor, Laura), and, most engagingly, involvement with a ragtag group of amateurs who call themselves the Late Starters Orchestra. It’s a no-audition string ensemble that meets every Sunday afternoon in a former coat factory in Manhattan, founded on the belief that, as Goldman puts it, “playing music should be accessible to all, not just the elite, not just the talented, not even just the good.” A seventy-something woman named Mary neatly captured the LSO philosophy when she talked Goldman down from his anxiety that he might not be “good enough” for a particular musical venture. Do it now, she told him, and don’t worry about your proficiency; “you may not live long enough to be ‘good enough.’”

Other LSO members also have the right attitude toward midlife learning. A cellist named Elena, for example, spent most of the group’s rehearsal sessions in bursts of laughter. As she explained to Goldman, she preferred to relax about the quality of her playing, instead of obsessing over it—“to relish the flubs and give myself permission to pursue something I have no hope of ever mastering.” That’s also what Goldman aims for, though permission to be mediocre hasn’t come naturally to him: He recounts many moments of frustration, and more than a few in which he wondered what he’d been thinking when he set himself that birthday-party goal.

The book suffers a bit from some confusing chronology, and it’s weakest when Goldman tries to go broad. He has nothing all that interesting to say about how baby boomers are aging differently from their parents’ generation—moving with determination into their sixties and beyond with verve and enthusiasm for life’s “third chapter.” Nor does he uncover any arresting new insights about the changes the digital revolution has brought to his profession of journalism. But when he focuses on the cello itself, and on his personal life and personal mission, the book is absorbing and sweet. The climactic scene at Goldman’s birthday party, with a hundred or so friends and family members in attendance, is especially lovely.

At the beginning of this cello odyssey, the author relates a Jewish myth about the angel Gabriel. (Judaism is central to Goldman’s life; it’s the subject of his three earlier books, and he mentions it often here.) Before Jewish children are born, the story goes, Gabriel visits each child to teach all of Jewish lore, law, and wisdom. He carries a lantern into the dark womb to light his way. Just before the baby is born, Gabriel blows out the lantern and strikes the child on the mouth, obliterating any memory of what the baby had been taught. In this way, according to legend, life consists of “reclaiming what we already know.”

That’s what music is like for Goldman. As he begins to tackle the cello in his late fifties, he writes, “I sometimes have the sense that I am recapturing something intrinsic to me rather than learning something alien and new.” What a beautiful idea. I didn’t manage to bring off that moment of recaptured inner proficiency with the cello—or with any of the dances, languages, or art forms in which I dabbled. But that sense of rediscovering or reclaiming one’s voice is an essential human endeavor, as the engaging and uplifting saga of Goldman’s progress toward his triumphant birthday concert reminds us. Maybe I’ll try my hand at tennis.

Robin Marantz Henig is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine and the author of nine books, including The Monk in the Garden (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000), Pandora’s Baby (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2004), and Twentysomething (Hudson Street, 2012), coauthored with her daughter Samantha.