In a cartoon that earned him a Pulitzer Prize, Bill Mauldin shows two men at hard labor in a Soviet gulag. “I won the Nobel Prize for literature,” one tells the other. “What was your crime?” In 1958, when the cartoon was published, it was obvious that the hapless Nobel laureate was supposed to be Boris Pasternak, whose literary achievements earned him expulsion from the Union of Soviet Writers and harassment so unnerving it pushed him to the verge of suicide. “It is not seemly to be famous,” a poem by Pasternak begins. “Celebrity does not exalt.” Yet after the 1957 publication of his only novel, Doctor Zhivago, Pasternak, already celebrated as one of Russia’s leading poets, had unseemly celebrity thrust upon him. His novel earned him adulation abroad (he won the Nobel in 1958) but acrimony at home. Admirers and detractors alike were convinced that what Pasternak had written was of consequence to the fate of civilization.

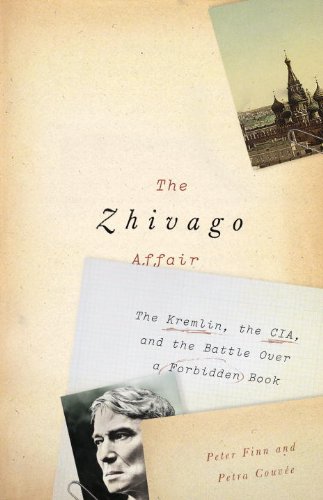

In The Zhivago Affair, Peter Finn and Petra Couvée evoke a lost era, when a mere book could affect the geopolitics of the nuclear superpowers. The Zhivago Affair is a case study in splenetic literary reception. Finn, the national-security editor of the Washington Post, and Couvée, who teaches at Saint Petersburg State University, have produced a riveting account of how Doctor Zhivago came to be written, released, revered, and reviled. They have drawn not only on archival documents and interviews with surviving actors in the international drama but also on newly declassified files of the Soviet, American, and Dutch intelligence services.

Pasternak managed to survive the reign of terror that killed his friends and fellow poets Osip Mandelstam and Titsian Tabidze. Though he defended Nikolai Bukharin against spurious charges of sedition and resisted pressure to denounce Anna Akhmatova for reactionary aesthetics, he avoided imprisonment and worse; in the decades following the Revolution, almost 1,500 writers were executed or perished in labor camps. In 1936, Pasternak did write two sycophantic poems in praise of Joseph Stalin, but he tried in general to avoid political entanglements and their consequences. Under a ruthless regime that specifically targeted poets, his survival seems as arbitrary as the arrests of other writers. Pasternak himself speculated that Stalin spared him because he regarded the poet as some sort of “holy fool.” Still, his poetry was accused of “reactionary backward-looking ideology” by literary apparatchik Alexei Surkov. Unable to publish, Pasternak struggled to make a living as a translator of Goethe, Rilke, Shakespeare, Tagore, Verlaine, and others. Although the poet himself was never sent to a gulag, Olga Ivinskaya, who was openly his lover throughout most of his marriage to his second wife, Zinaida, was sentenced to five years of hard labor because of her relationship with Pasternak. Pregnant with his child, Ivinskaya, who was the model for the character Lara in Doctor Zhivago, served from 1950 until pardoned after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Though most critics still consider Pasternak’s poetry his greatest achievement, he yearned to create something more ambitious. “Poems are unimportant,” he declared. “I don’t understand why people busy themselves with my verses.” By 1945, he began to conceive a novel about the turbulent experiences of a Russian physician and poet—and Russia itself—from the abortive 1905 Revolution to World War II. The book is not exactly anti-Bolshevik, but neither does it portray in heroic terms the violent convulsions that transformed Russia. Tentatively titled Boys and Girls, it evolved into the manuscript of Doctor Zhivago that Soviet editors refused to publish. When an emissary of Italian publisher Giangiacomo Feltrinelli visited him in his dacha, Pasternak slipped the book to him, to be smuggled out of the country. For all the grief it brought him, the author called his completed novel “my final happiness and madness.” Its publication in Italy in 1957—and soon throughout the West—infuriated the Kremlin and helped reverse the cultural Thaw following Nikita Khrushchev’s denunciation of Stalin’s enormous crimes. Khrushchev himself encouraged the campaign against Doctor Zhivago, though following his own fall from power, he would admit: “I should have read it myself. There’s nothing anti-Soviet in it.”

Soviet media raged over the perfidy of a novelist who defied the formulas of socialist realism and called for his deportation. Since the book was not legally available, few had actually read it, though it would later achieve wide circulation as samizdat. Nevertheless, angry crowds massed outside Pasternak’s dacha. At an emergency meeting of the Union of Soviet Writers, in a scene worthy of Orwell, members one by one condemned their erstwhile colleague. Pasternak felt compelled to decline the Nobel Prize.

Though its author was unable to collect royalties, Doctor Zhivago became a huge best seller abroad. Finn and Couvée document the role of clandestine American intelligence in shaping the novel’s reputation. The CIA obtained a copy of the Russian manuscript and, after arranging for covert publication in the Netherlands, put thousands of copies into the hands of travelers bound for Eastern Europe—part of a campaign in which, between 1956 and 1991, the CIA distributed ten million books within the Soviet bloc. It is both reassuring and unnerving to recall the Cold War as conducted with books rather than tanks. Both the CIA and the KGB implicitly endorsed Maxim Gorky’s proclamation that “books are the most important and most powerful weapons in socialist culture.” No recent book other than Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses has shaken the world in quite the way that Pasternak’s and, sixteen years later, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago did. Bemused by a vanished world in which authors counted for so much, Finn and Couvée conclude their book in awe that “all these years later, in an age of terror, drones, and targeted killing, the CIA’s faith—and the Soviet Union’s faith—in the power of literature to transform society seem almost quaint.”

Steven G. Kellman is the author of Redemption: The Life of Henry Roth (Norton, 2005) and The Translingual Imagination (University of Nebraska Press, 2000).