FOR A LONG TIME, it has been unclear why the Americans are still fighting in Afghanistan. In 2001, when the Bush administration launched the invasion, the mission was to destroy Al Qaeda and the Taliban leadership. But thirteen years later, with Osama bin Laden dead and Al Qaeda’s operations and leaders dispersed well beyond Afghanistan’s borders, how can we sum up the main objective of America’s longest-running war? Who is the enemy now?

Even during the run-up toAfghanistan’sApril presidential election, as bombs exploded at day-care centers and assassins shot up five-star hotels, those Talibs—were they Talibs?—likely still seemed faceless to Americans: men without families, histories, or names. The Afghans are too mysterious, too far away. Somehow, no matter how many thousands of journalists, soldiers, and aid workers are sent to Afghanistan, their collective knowledge of this American war still fails to penetrate a society so well defended against its imperial self.

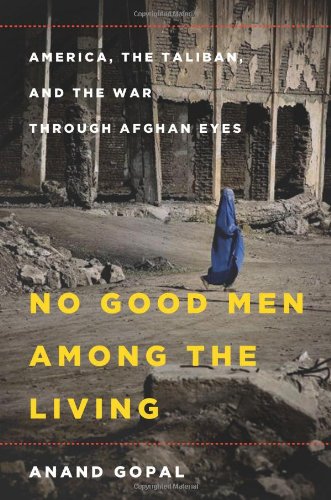

That’s why Carlotta Gall’s The Wrong Enemy and Anand Gopal’s No Good Men Among the Living are such valuable guides to this conflict. Both books show the confident clarity that comes from perspective, time, and painstaking effort. For an American reader, they are a reckoning with denial, like discovering a loved one’s double life; what they describe doesn’t at all resemble the past we thought we knew. Their combined testimony prods us to an important, if painful, conclusion: The problem in Afghanistan was not that the good guys made mistakes in the good war, but that the Americans were careless, thuggish, and criminal in prosecuting a war they didn’t understand.

Of the two books, The Wrong Enemy is the more specific and daring indictment, though not long on the intimate details of Afghans’ lives. In sketching the decade she has spent in Afghanistan as a New York Times correspondent, Gall first provides an overview of the various players who contributed to the war’s deepening chaos.She catalogues the Americans’ misdeeds: the incineration of villages; the detaining, torturing, and killing of tribal leaders sympathetic to the Americans’ cause; the imprisonment of those men in Guantánamo. Of the “two hundred and twenty Afghans . . . sent to Guantánamo Bay,” she writes, “only a dozen . . . were important Taliban figures.” She devotes one chapter to the shortcomings of President Hamid Karzai—namely, corruption, incompetence, and the coddling of warlords—and she also details his anguish. “He became increasingly distressed with each new case of civilian casualties and railed against the bombardments and night raids that caused them,” she writes. It’s a welcome piece of tough but sympathetic analysis at a time when the weeping president is often dismissed merely as a crazy person, ungrateful for all that the Americans have done.

Ultimately, however, Gall’s purpose is to persuade us that the Americans’ true foe in Afghanistan is Pakistan. (The book’s title is taken from a remark made by the late diplomat Richard Holbrooke, who was appointed as special US ambassador to both countries in 2009: “We may be fighting the wrong enemy in the wrong country,” he said.) For some years, the American policy makers didn’t perceive the contours of Pakistan’s “double game,” its simultaneous support for the Taliban and the United States. Gall chronicles how this double game evolved, how it derailed what might have been America’s quick triumph, and how this deception included the protection of Al Qaeda leaders on Pakistani soil—including, most notoriously, Osama bin Laden himself.

When the US invasion began in the fall of 2001, almost all of the Taliban’s leaders and their Al Qaeda allies fled across the eastern border into Pakistan, where they reconvened with the ISI, Pakistan’s intelligence service. Since the 1970s, the Pakistanis had deployed the destabilizing influence of Afghan proxies to ensure that India would never attain power in Afghanistan, and to suppress their own restless population of Pashtuns, as they threatened to join forces with their Afghan counterparts to create an independent Pashtun state. During the Soviet-Afghan war, the United States and Pakistan together, in a supremely cynical alliance, created a generation of Islamic fundamentalists—designing jihadi textbooks and sending MANPADs (i.e., “man-portable air-defense systems”) into Afghanistan. A group of mujahideen eventually became the Taliban. Mullahs occupied a pivotal position within Afghanistan to serve all these Pakistani aims: They were Pashtun but not nationalist or separatist, and espoused a syncretic vision of tribal values and sharia law that, over time, drew on fundamentalist ideas from Pakistani madrassas.

After the invasion, the Pakistanis gave the Taliban cover and told them to lie low. At that time, the United States was courting Pakistan’s new president, General Pervez Musharraf—the man whose name famously eluded George W. Bush in his reply to a debate question during the thick of the 2000 presidential campaign—offering him millions of dollars in aid to ally with them against Al Qaeda. By extension, so the US theory went, the gaudy purchase of Musharraf’s influence would also align Pakistan against the Taliban. Instead, it opened up a critical rift within Pakistan’s own regime. When Musharraf decided to support the Americans, Gall writes, he “was going against nearly thirty years of Pakistani strategic thinking.” The ISI was not prepared to do the same. As the Americans’ attention drifted to Iraq in 2003, the ISI sent the Taliban back to fight.

Essentially, Gall argues, the Americans were giving the Pakistanis money to kill American soldiers in Afghanistan and to hide the United States’ premier enemy in the war on terror within their borders. It’s impossible to know whether she’s right that the Pakistanis knew of bin Laden’s safe house in Abbottabad, but given the history and ample evidence she provides, confirmation of such advance knowledge wouldn’t be at all far-fetched or surprising. Nonetheless, Westerners continue to be shocked by Pakistan’s backstabbing behavior, as if international alliances are values-based blood pacts rather than on-and-off affairs of grim convenience.Gall’s book largely omits a central theme in the history of US-Pakistani relations—that the CIA has been subverting democracy in Pakistan since the 1950s (often by supporting the military as well as the ISI). Many generations of Pakistanis have grown up believing, with good reason, that the whims of the United States have been instrumental in shaping their collective fate (that few Americans share any corresponding memory of this relationship is a testament to its disproportionate nature). It’s crucial to understand that dynamic in order to grasp anything about Pakistan’s convoluted foreign and domestic policy today.

In Anand Gopal’s extraordinary No Good Men Among the Living, the specter of Pakistan is acknowledged but hovers in the background; instead, it’s mainly the Americans themselves who managed to bring the Talibs back to fight. The book tracks the invasion’s impact upon a handful of diverse Afghan figures. (There are no American characters in this book, and the effect is radical.) Many policy makers have suggested that the Americans failed in Afghanistan in part because they were distracted by the war in Iraq, but Gopal disagrees. “The argument rests upon a key premise,” he writes, “that jihadi terrorism could be defeated through the military occupation of a country. . . . Travel through the southern Afghan countryside, and you will hear quite a different interpretation of what happened.”

Gopal’s method of going deep into the lives of several Talibs, warlords, and ordinary Afghans—he includes an exhilarating portrait of one Afghan woman—demonstrates how different the Americans’ “mistakes” feel when the dead, injured, and traumatized people have been amply humanized. (Most portrayals make Talibs, especially, seem like disposable brutes.) For starters, Gopal has interviewed many Talibs who say they had put down their guns and returned to normal life after the invasion. “Their movement had failed a great test of endurance and legitimacy,” he writes of the Talibs in recounting the odyssey of one such figure, Mullah Manan. “Now the mandate of authority was passing to the Americans and their Afghan allies. If they did right in the coming years, they could keep men like Mullah Manan home forever.” There’s more: “Within a month of its military collapse, the Taliban movement had ceased to exist. When religious clerics in Pakistan launched a fund-raising campaign to get the Taliban back on their feet and waging ‘jihad’ against the Americans, it was roundly rejected by the Talib leadership.” Nevertheless, Gopal notes, the Americans did not distinguish between the ongoing jihad of Al Qaeda and the more nationalist concerns of the Taliban.

Instead, they began imprisoning, torturing, and killing any Afghans whom they could charge with an allegiance to either Al Qaeda or the Taliban, no matter how flimsy the evidence of such an affiliation might have been. We are not talking about the oft-repeated “errant bomb strikes” or the gentle mishandling of “detainees,” but rather the intentional killing of suspects and civilians and the brutalizing of prisoners. To find the guilty, the Americans followed the same basic playbook they’d employed in turning Musharraf in Pakistan: They dispensed millions of dollars to Afghan warlords, former enemies of the Taliban now happy to incriminate their old foes. The associates of notorious Kandahari gangster Gul Agha Sherzai, for example, “became the Americans’ eyes and ears in their drive to eradicate the Taliban and Al Qaeda from Kandahar,” Gopal writes. “Yet here lay the contradiction. Following the Taliban’s collapse, Al Qaeda had fled the country, resettling in the tribal regions of Pakistan and Iran. How do you fight a war without an adversary?” Men like Gul Agha saw an opportunity; his “personal feuds and jealousies were repackaged as ‘counterterrorism,’” Gopal writes.

While possible allies and supporters of the new Karzai government in Kabul were eliminated, Sherzai and other warlords were rewarded with business empires “strung across the desert, garish villas abroad.” The Americans, meanwhile, “carried out raids against a phantom enemy, happily fulfilling their mandate from Washington,” and in the process they became a sort of warlord corporation in their own right. One American leaflet dropped by a plane in Kandahar read, “Get Wealth and Power Beyond Your Dreams. Help Anti-Taliban Forces Rid Afghanistan of Murderers and Terrorists.”

Gopal details what happened once the Americans captured innocent Afghans—bread bakers, politicians, teenagers—in two brilliantly written chapters about the Americans’ jails at Bagram and Kandahar airfields, and at Guantánamo Bay. Noor Agha, for example, a resolutely anti-Taliban former member of the national police, is blindfolded and hung from his shackled wrists and attacked by dogs. Commander Naim, “an eminent tribal leader” and “ardent supporter of the Americans,” is arrested, blindfolded, and made to strip naked. American soldiers also arrest the vehemently pro-American Samoud Khan—he was even on the Special Forces payroll—along with eight of his associates, one of whom is a twelve-year-old teaboy. All of them are sent to Bagram or Guantánamo. The list of wrongly charged, detained, and abused prisoners multiplies: One Afghan is accused of being a member of a group that no longer exists; another is thrown in Guantánamo when he’s mistaken for a different man altogether, who was already detained at Guantánamo at the time; another is thrown in jail at Bagram for having links to the US contractor who built Bagram. If it sounds like someone was falsifying evidence, that’s because someone was: None of these victims was a member of the Taliban or Al Qaeda. Many had been the closest thing to what the Americans in Afghanistan could call their friends.

This heartbreaking and absurd set of misguided assumptions created a thriving war. The Afghans fighting the US occupation had no trouble finding recruits, thanks to the botched US occupation: All these abused and disappeared Afghan men had families, tribes, and villages, and many merely wanted to protect their homes from American soldiers. Akbar Gul, one of the central figures in Gopal’s narrative, left the Taliban after the invasion, returned to civilian life as a cell-phone repairman, and ultimately rejoined the Taliban because, he tells Gopal, it felt like the Americans were “colonizing us, just like the British.” By this point in No Good Men Among the Living, the reader will find that characterization kind. Here is one typical example of how these Americans conducted their night raids on innocent Afghan villages:

As the soldiers approached a home, a dog growled and they shot it. A villager ran out, thinking a thief was on the premises, and they shot him too. His younger brother emerged with a gun and fired into the darkness, yelling for his neighbors. The soldiers shot him as well, and the barrage of bullets also hit his mother as she peered out a window. The soldiers then tied the three bodies together, dragged them into a room, and set off explosives. A pair of children stood watching, and they would later report the scene. An old man stepped out of the neighboring house holding an oil lamp. He was shot. His son ran out to help, and he, too, was shot.

The Americans weren’t colonizing anything. They were just killing people. Gopal makes us see this awful truth plainly for what it is, and that is his literary achievement.

The Americans finally tried a different approach to the Afghan occupation in 2009, long after the Taliban had entrenched themselves throughout the country, ruling the highways and dispatching suicide bombers and planting IEDs. That year, General Stanley McChrystal promised a new counterinsurgency doctrine, one that was supposed to focus more on protecting Afghans and less on air strikes and remote firepower. “All ISAF personnel must show respect for local cultures and customs and demonstrate intellectual curiosity about the people of Afghanistan,” McChrystal said. With this decree came a fascinating military program called the Human Terrain System, which has been unsparingly dissected by the journalist Vanessa M. Gezari in another indispensable recent book on the Afghan conflict, The Tender Soldier.

It speaks volumes about the entire American misadventure that its military leaders were seeking to instill intellectual curiosity about the invasion’s subjects by executive fiat, eight years later. It’s also no great surprise that this frantic campaign of anthropological catch-up was likewise condemned to failure—a casualty, as Gezari shows, of all-too-typical American mandates of rushed bureaucratic box checking, self-sabotaging feints at cultural sensitivity, and crude corporate-style cost cutting.

In a sense, these recent appraisals of the Afghan occupation confront American readers with the same unwelcome truths that beset the invasion at its outset. Gall supplies a substantial accounting of the United States’ mistaken assumptions about the basic operations of power politics in the region, while Gopal takes full measure of the tragic costs of those failures on the ground for innocent Afghan civilians. And ultimately, the grim conclusion that each author reaches turns on the same basic moral: No matter what Americans had wanted Afghanistan to be—the place where September 11 was avenged, the redemption of all American sins, the proof of magical American powers—war could never be anything other than war. Yet this violent American fantasy will forever be the Afghans’ burden.

Suzy Hansen is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine and has written for many other publications. She lives in Istanbul.