Ariel Schrag, now in her mid-thirties, has been a force in gay pop culture since she was fourteen. A prolific cartoonist, she started publishing her own autobiographical comic-book series, Awkward, her freshman year at Berkeley High, in 1995. Schrag produced a differently titled comic-book series for each year she was in high school—Definition, Potential, and Likewise followed Awkward. The appeal of her comics, which chronicle her own coming out, includes a razor-like attention to details of teenagers’ lives, as well as a richly expressed (you guessed it) awkwardness. Her comics attend to masturbation, body image, sex, drugs, family, and biology class—to the ups and downs of the teenage world, where every interaction feels negotiated and tentative. Her autobiographical works are funny and unusually raw and candid, qualities that would continue to resonate in her scattered later comics and in her writing for the hit television show The L Word.

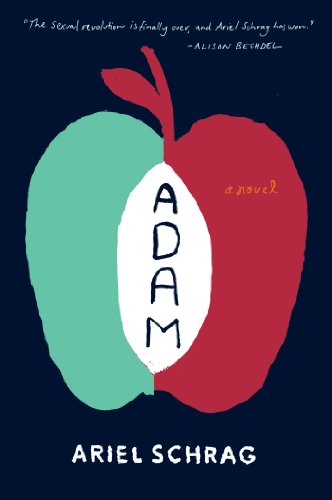

It might come as a surprise, given the fact that Schrag has been a lesbian icon for half her life, that the title character of her first novel, Adam, is a straight male teen. But this novel shares many qualities with her past work. Adam mixes modes freely, playing to Schrag’s strengths in her comics—the ability to record unflinchingly a person’s abject self-consciousness—and featuring the kind of melodramatic set piece that made The L Word so ridiculous (yet so beloved). Compulsively readable, Adam sometimes seems like a YA novel, only with way more explicit sex. The book is also philosophical, presenting, at its core, a question about gender, desire, and subjectivity: Is sexual identity defined by who you have sex with, or who you think you’re having sex with?

At the novel’s beginning, Adam Freedman goes to a sheltered Bay Area private high school, and his life is defined by his failing struggle to be popular. The opening in California has some of the freshest writing in the novel, as Schrag almost gleefully enumerates the socially painful details, both amusing and sad, of Adam’s universe, including the lengths he goes to entertain Brad, his childhood best friend. Adam suggests that he and the now-popular Brad spy on his sister Casey while she has sex with her girlfriend. He hopes that delivering a live sex show will impress Brad, but his friend turns on him: “Watching your sister? What’s wrong with you?”

Adam has never so much as kissed a girl, while his buddies are starting to couple up. His growing insecurity inspires him to jump ship and move to Brooklyn for the summer to crash with his beautiful, gay older sister. Casey, a Columbia biology major, lives in Bushwick, and Adam is soon immersed in her “genderqueer” scene of friends and lovers. All he wants is some heterosexual approval, but there is barely a straight woman in sight—there are no straight women characters at all, in fact, once Adam lands in Brooklyn. What he discovers in New York is disorienting: First, his perfect sister (whose gayness, unknown to their parents, he already accepts) dates trans men. Second, when he’s out with Casey, his seventeen-year-old-boy physique is mistaken for that of a trans man. In one hilarious scene at the (now-defunct) East Village bar the Hole, Adam is flabbergasted and overjoyed when a gorgeous girl comes on to him: “‘Oh God, you’re packing,’ said Calypso. ‘That is so fucking hot.’ Packing? Adam didn’t know what she was talking about and didn’t care.” But soon Adam does know what she’s talking about. He falls for Gillian, a woman he notices at a political rally, and, using what he’s learned while living with his sister, convinces her that he’s trans. The two begin dating. Gillian, who “majored in being gay” at Smith, wouldn’t date a straight man if she knew he was a straight man; she opens her eyes to Adam only because she thinks he’s trans. With its misleading straight protagonist, the novel cleverly reverses the common presentation of trans people as deceptive.

Schrag does two things very well: She lets us see a young, exploratory, queer New York scene through Adam’s naive, uncensored perspective, which has nothing to do with anything remotely politically correct. Adam freely offers his observations about people’s self-presentation, and about who is “obviously” this or that. (Of course, very few people he cares about wind up being “obviously” what Adam thinks.) Schrag also deftly evokes a particular kind of self-awareness with her cast of characters who are frequently anxious about passing—passing as “popular,” as a man, as a woman, as straight, as Jewish (a performance one character enacts for her Hasidic landlord). As the book’s anchor, Adam provides readers with the opportunity for a twinned reaction: His haplessness can be bemusing, but he also offers a fresh and energetic encounter with self-consciously constructed social scenes and lexicons. Schrag’s gentle targets here are immature self-righteousness—on display in a very funny discussion of pronouns—and posturing, particularly of certain self-involved characters whom Casey seems wont to date. Schrag allows Adam, crucially, to be more than a cipher; he is not always likable, but he grows to inhabit a quirky charm that makes his love affair with Gillian credible.

The gimmick at the center of Adam is a good one, and the complicated issues it provokes are profound. Adam doesn’t offer any answers, although it does create a scene in which “answers” aren’t entirely necessary: Everybody winds up being more flexible than one would initially expect. The tone of the book varies widely, from goofy yet in-depth descriptions of a women-only sex-play party to political anger and despair when a transgender teen is murdered. And yes, it all comes to a head at the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. Or rather, Camp Trans, its coinciding protest demonstration. Schrag deftly balances the use of stereotypes with textured, sharply observed interactions, especially in the banter between siblings as they navigate acceptance. Ultimately, Adam is more unwieldy and unfocused than her single-year comics about gender, sex, and self. But Schrag’s novel forcefully inhabits its range of characters and perspectives, resulting in a more multivalent exploration of a theme she’s grappled with all along: awkwardness.

Hillary Chute is the author of Outside the Box: Interviews with Contemporary Cartoonists (University of Chicago Press, 2014).