“HE WORE A PURPLE PLAID SUIT his staff abhorred and a pinstripe shirt and polka-dot tie and a folded white silk puffing up extravagantly out of his pocket.” This was not some tea-sipping Edwardian dandy. It was Ronald Reagan announcing his presidential candidacy at the National Press Club in November 1975, as described by the historian Rick Perlstein. Back then, Reagan was, to most people, a novelty candidate, with a bit of the fop or eccentric about him. Political affinities and antipathies have since hardened into a useful but wholly unreliable historical “truth” about Reagan’s political career, one that casts him as either a hero or a villain. It requires an effort of the imagination to see him as the voters he addressed did.

Most historians of the late twentieth century wallow in their youthful prejudices. Not Perlstein. For two decades, he has been scraping away layers of self-justifying platitudes and unreliable recollections. A leftist (one assumes) with an empathy for insurgents and underdogs of all stripes, he has opted not to write the eleventy-zillionth recapitulation of this or that New Deal or civil-rights milestone. He has focused instead on the followers of various reviled and misunderstood conservatives, particularly Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, sometimes revealing in them an affinity for straightforward radicalism. He is a man of the archives—patient, punctilious, refreshingly disinclined to moralize.

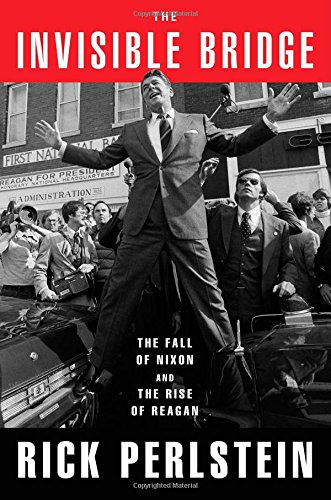

Perlstein’s ambitious new chronicle, The Invisible Bridge, runs from Nixon’s reelection in 1972 to the 1976 Republican-primary campaign, when a staffer to Nixon’s successor, Gerald Ford, warned in a memo, “We are in real danger of being out-organized by a small number of highly motivated right-wing nuts.” At the 1976 party convention in Kansas City, Ford fended off Reagan’s challenge only by consenting (partly on the advice of his chief of staff, one Richard Cheney) to reorient his platform and organization around God, tax cuts, and military strength. Beneath a roiling sea of detail, Perlstein offers us a reinterpretation of the Watergate scandal and its aftermath. To say “the system worked” in ridding the country of Nixon is to tell only half the story. Having consented to an unflinching probe of the US presidency that culminated in Nixon’s resignation, the American public recoiled in horror from what they had done and wrought punishment on the Democratic establishment, which they blamed for carrying it out. One instrument of that punishment was Ronald Reagan.

Nixon’s attorney general John Mitchell was not wrong when he told a reporter in the late ’60s: “This country is going so far to the right you won’t recognize it.” He and the administration he served were just too corrupt to reap the fruits. True, attitudes changed toward marijuana, sex, spoliation of the environment, and women in the workplace. But this happened faster among elites than among ordinary Americans—the demographic and geographic rearguard of the ’60s lifestyle revolution that conservative leaders would come to rebaptize the “real” America. The ’70s also marked the high tide of the American Right. Much of the country was discomfited by protests, drugs, and crime. Perlstein’s Nixonland (2009) laid out the canny and sometimes sinister ways Nixon exploited this discomfiture. In The Invisible Bridge, he describes how Nixon invented the category of soldiers “Missing in Action” (who, in previous wars, would have been called “Killed in Action / Body Unrecovered”) to rile up the home front against peaceniks, making it seem as though they were determined to abandon soldiers on the field of combat.

Perlstein’s account of the Watergate break-in and cover-up—as a misdeed unparalleled in the history of the office but of a piece with Nixon’s paranoid character—is conventional. He sees Nixon’s disgrace as condign punishment for genuine abuses of power. But the Watergate investigation was about something else, too. It was the response of a political establishment to an antiestablishment political movement. Nixon bound the Sunbelt, the South, disaffected urban Democrats, and supporters of the Vietnam War together with Republican businessmen and boosters, and he managed, in 1972, to win by what is still the largest popular margin (almost eighteen million votes) in US presidential history. The Watergate investigations, whatever their legal justification, had the political effect of damming a democratic tide.

Perlstein believes Nixon was a dangerous man, one capable of “mafia-style threats.” But his narrative provides the basis for a different view: Nixon lost his job because people feared him less than they did his adversaries. One is struck on numerous occasions by the president’s extraordinary complaisance. John Dean, in the testimony that ultimately damned Nixon, said he had “told the President that I hoped that my going to the prosecutors and telling the truth would not result in the impeachment of the president. He jokingly said, ‘I certainly hope so also,’ and he said it would be handled properly.”

Nixon abused the IRS, but obviously didn’t control it—it claimed half a million dollars in back taxes from him in 1974. The San Clemente Inn, which used to host members of the White House staff on trips to Nixon’s California retreat, evicted them. The release of transcripts of tapes made in the Oval Office was, Perlstein acknowledges, the “biggest blunder of Nixon’s political career.” If impeachment was warranted because Nixon was corrupt, it was actually carried out because he was weak and trusting and his party upstanding. Six GOP senators said in 1973 that they would not run for reelection unless Nixon spoke about the Watergate break-ins. Nixon’s successors have not made that mistake again, whether in last decade’s Iraq War inquiries or this decade’s allegations of IRS malfeasance. Therefore, no “system” worked in Watergate. It was a form of oversight that could be used only once, and on an administration caught by surprise.

It is not far from this vantage to seeing Watergate as a kind of conspiracy or coup. Early on in the scandal, Democratic adviser Clark Clifford suggested a resolution of Watergate that involved Vice President Spiro Agnew’s resignation and the appointment of a successor acceptable to Congress, to be followed by Nixon’s resignation—almost exactly what happened over the following year and a half. North Carolina Republican senator Jesse Helms complained that the misdeeds of Nixon’s predecessors John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson made “Watergate look like a Sunday school picnic.” Nixon aide Patrick J. Buchanan testified that a lot of the administration’s “dirty tricks” were inspired by the Kennedy fixer and Watergate-era chairman of the Democratic Party, Larry O’Brien.

This view, Perlstein shows, triumphed. In December 1975, the editorial page of the New York Times avowed: “By the time Richard Nixon became President, the practiced seaminess had become so entrenched that the deception of Watergate flowed with alarming naturalness.” By then, Senator Frank Church of Idaho, slated to investigate US intelligence abuses, had shown a “willful resistance,” as Perlstein puts it,

in following his own evidence where it frequently led. He had imagined, when he took on this inquiry as his own, that it would help put the final nails in the coffin for the legacy of Richard M. Nixon. He hardly knew how to respond when so many of the most frightening discoveries pointed instead to the administration of John F. Kennedy—at whose 1960 convention he had delivered a striking keynote speech.

A separate House inquiry, by Long Island Democratic representative Otis Pike, was suppressed by Congress itself; the Village Voice published a leaked copy. (Perlstein calls it a “literary masterpiece.”) If this new, Watergate-style government was a “system,” it was one the public appeared to be repudiating. A mood of nostalgia was sweeping the country. The results included American Graffiti, the television series Happy Days and The Waltons—and the presidential bid of a man born well before Nixon and Kennedy.

Perlstein describes his massive book as a “sort of biography of Ronald Reagan.” He can’t stand him. Reagan comes off as a bullshit artist of a kind that the “wondrous technology” of the Internet makes it easier to expose. Perlstein finds evidence for few of the stories Reagan told about himself, the country, and its people. “I didn’t leave the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party left me,” Reagan often said, even though the party had tacked rightward between the candidacies of Harry Truman (whom he supported) and Kennedy (whom he opposed). His so-called Eleventh Commandment (“Thou shalt not speak ill of another Republican”) was more opportunistic than loyal: In the 1966 California governor’s race, his aides thought a focus on character would damage him. But that is not the whole story.

“Reagan’s interpersonal intelligence,” Perlstein writes, “was something to behold.” He saw things no one else saw. His greatest triumphs came on issues that he advanced in the face of unanimous advice to the contrary. He defeated a popular California governor, Pat Brown, by attacking campus radicalism when “the most sophisticated public opinion research that money could buy told him not to touch it,” Perlstein writes. Reagan called for smaller government when other Republican governors were trying to rally the public around “strong land-use planning.” He drove much of the country into a frenzy over the US handover of the Panama Canal, a transition that had been uncontroversially under negotiation for decades. And, alone among Republicans, he refused to hedge his bets about Richard Nixon—he stood squarely by him, even sloughing off Nixon’s ingratitude and contempt. What did Watergate say about America? Nothing, Reagan said. That is what most Americans thought, or wanted to think.

Reagan is a protean personality. In certain lights, he was a Cold War liberal who just had an ear for right-wing dialect. As California governor, he doubled the state budget, passed a strict gun-control law, and signed the most liberal abortion law in the country. Perlstein is struck by “how effortlessly his mind swirled fiction and fantasy into soul-satisfying confections.” But this is the basic work of all democratic politicians, liberal and conservative, and it is wrong to fling around the word lie, as Perlstein often does, to describe such flights. So, for instance, when Reagan claimed that segregation in the military was corrected “in World War II,” he was, yes, three years off—Truman signed the executive order desegregating the armed forces in 1948. But he was also right to identify the war as having brought about a change in ideas about race. When Reagan said welfare could erode national character, his numbers were inaccurate—but the alternative, as voters saw it, was politicians who would deny any evidence to that effect.

In his youthful work as a sportscaster in the Midwest, Reagan stumbled into the perfect formula for democratic leadership: He gained “the company of VIPs [while] maintaining an image as an ordinary guy.” After a film career that Perlstein portrays as a drawn-out failure—appearing in B movies such as Stallion Road (1943) and Hong Kong (1952)—Reagan was able to re-create this same formula in Hollywood. His agent was Lew Wasserman, who specialized in “incorporating” stars so they could pay 25 percent capital-gains rates rather than 90 percent income tax. As head of the Screen Actors Guild, Reagan did Wasserman a favor: He overturned a guild rule that blocked talent agencies from producing TV series. And Wasserman helped launch Reagan’s new career: hosting a show of film shorts called The General Electric Theater.

GE aimed to create an “electrical consciousness” among American shoppers (a strange echo of Leninism), and it turned Reagan into what TV Guide called GE’s “ambassador of all things mechanical” (a strange forebear of Silicon Valley PR). GE exec Lemuel Boulware, whose career and methods fascinate Perlstein, enlisted Reagan in an ongoing effort to promote free-market thinking among GE’s employees. Reagan traveled to many GE plants. As in his sportscasting career, he was a star of sorts, but one with almost daily experience connecting to like-minded Americans of all classes. He also learned certain political skills, dropping his on-screen rants against the government-owned Tennessee Valley Authority, for example, once GE executives let him in on the secret of where the TVA bought its fantastically expensive turbines. This was the opportunistic and adaptable personality who put himself at the head of an insurgency against Gerald Ford, to be conducted in the name of adamantine principle.

A good deal of the drama of The Invisible Bridge comes from the author’s unmistakable affection for Ford. Perlstein is swept up—just as people were in 1974—by the speech Ford made on assuming office from Nixon (“Our long national nightmare is over”), which Perlstein regards as a “masterpiece of American oratory.” He also reproduces, but is less moved by, the equally beautiful declaration of pardon for Nixon, which Ford read out months later. (“My conscience tells me clearly and certainly that I cannot prolong the bad dreams that continue to reopen a chapter that is closed. My conscience tells me that only I, as President, have the constitutional power to firmly shut and seal this book.”) Ford was “solid.” He believed in modesty, both for himself and the nation he led. A Big Ten varsity athlete, an excellent downhill skier, “the most physically accomplished man ever to have held the office,” he accepted with equanimity comedians’ interminable jokes about his being a klutz. What Perlstein appears to like most about Ford, though, is his family.

Betty Ford was modern and liberal. She wanted the Equal Rights Amendment passed and abortion “taken out of the backwoods and put into the hospital where it belongs.” Ford’s approval rating fell twenty points after she speculated about her children smoking pot and having affairs in a 60 Minutes interview. The country eventually came around to his wife’s way of talking about these things, even if it would be too late for Ford. Perlstein is content to note that the family was considerably more upright than Reagan’s. “Here was the family of the family-values candidate,” he writes. “Four kids, seven marriages, zero college degrees, several expulsions from boarding school, two contemplated suicide attempts.”

THE PARADOX OF THE PERIOD Perlstein describes is that the Watergate investigations, envisioned as a means to restore responsibility and sanity to American politics, wound up bringing about its polarization. Democratic leaders of the ’70s had a beam in their eye. They recognized certain of their own flaws but not the biggest one—that they were turning into advocates for a cultural and economic elite rather than tribunes of the populace. Liberal sanctimony was the sin on which the modern conservative ascendancy was built, and Watergate made it worse. Yet this harsh lesson eluded the press that was writing about Watergate and its aftermath.

It does not elude Perlstein. Judge John Sirica appears in these pages as effective at wringing information out of the break-in defendants, but largely by abusing his sentencing authority. North Carolina Democrat Sam Ervin, who chaired the Senate panel investigating Watergate, will strike the reader as a Tea Partier avant la lettre, invoking the Constitution at the drop of a hat. Reading his grilling of Nixon aide Maurice Stans about how political backers had bought up tables for an undersubscribed vice-presidential fund-raiser, a practice common even today, you will find yourself rooting for Stans. “Mr. Chairman,” he replied, “I am not sure this is the first time that has happened in American politics.”

“Our country has lived through a time of torment,” said nominee Jimmy Carter at the 1976 Democratic Convention. “It is now a time for healing.” A skeptical translation might be: While dissent was a virtue when we were in opposition, it is a vice now that we are in power. Democrats faced a terrible problem of their own making. They had no ideology the public wanted, and their own post-Watergate congressional majority had inadvertently put in place a system in which ideology was all that mattered. A purge of committee chairmen reorganized the House on far more ideological lines. Limits on contributions to individual candidates made issue-oriented campaigns the main conduit of money into politics. Perlstein tells the story of Reagan’s plane waiting for hours on a Los Angeles runway while the campaign staff in Washington frantically tore open envelopes, trying to figure out if they had the money to fly it across the country. After Reagan won the North Carolina primary, thanks to Jesse Helms’s “revival tent” approach to mobilizing voters and donors, the money problems vanished once and for all. The price Ford paid for the nomination at the 1976 convention in Kansas City was what Perlstein calls “a pro-life, anti-détente, pro-gun, antibusing, pro-school-prayer platform.”

Perlstein’s books are big, in every sense of the word. His exuberant prose style will keep most readers from ever feeling stalled out. It also produces frequent solecisms (the Republican Party is in thrall to, not “enthralled by,” the cotton South; women used to be excluded, not “omitted,” from jury duty) and unmeant comic effects. Here’s how he characterizes Pat Buchanan’s White House job: “to shame media executives into spasms of contrition for tilting their organs to the left.”

Yet Perlstein knows so very much about American politics, some of it profoundly evocative of lost worlds and pregnant with understanding of our own: That the Watergate conspirator Jeb Stuart Magruder, as a Williams undergraduate, had taken an ethics course from the peace activist William Sloane Coffin, who once told him, “You’re a nice guy, Jeb, but not yet a good man.” That Frank Church had only one testicle. That Nixon adored Leonid Brezhnev and gave administration employees the afternoon off to wave hammer-and-sickle flags at him when he arrived for a state visit in 1973. That the Hollywood gossip columnist Louella Parsons was, like Reagan, from Dixon, Illinois. That Reagan loved horses even before he entered politics but, until he started getting photographed, hadn’t “dressed like a cowboy; he rode English style, wearing jodhpurs and boots.”

What places Perlstein among the indispensable historians of our time is his empathy, his ability to see that the roles of hero and goat, underdog and favorite, oppressor and oppressed are not permanently conferred—and that, for instance, an antibusing activist shouting down a suburban feminist at a Boston rally in 1975 was challenging the power structure, not upholding it. It requires such an empathy to reimagine the mid-’70s as a time, rather like our own, when almost nobody looking at the surface of day-to-day life was able to take the full measure of the resentment boiling just underneath it.

Christopher Caldwell is a senior editor at the Weekly Standard and a columnist for the Financial Times.