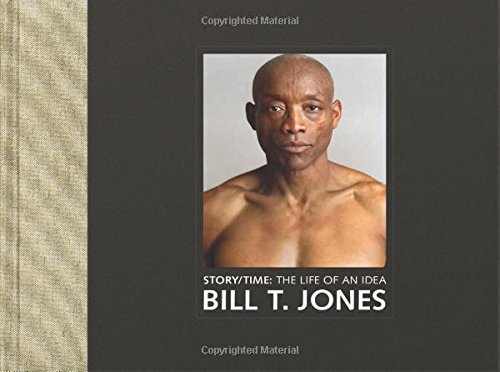

John Cage’s avant-garde compositional procedures, which value chance and avoid deliberate meaning-making, have had nearly universal application in the arts—in painting, poetry, and, especially, dance. In Story/Time, a collection of performance texts and lectures that reckon with the composer’s influence, the renowned choreographer Bill T. Jones describes a 1972 encounter in tones of awe. More than the music itself—“the sounds were of nature in constant interactive flux with electronic drones, whirring, whines, tweets, and scraping metallic noise”—what impressed the young drama student was Cage’s air of “sophisticated ‘remove.’” It suggested a “world of ideas,” inhabited by unassailable people who had rejected the pressure to connect and entertain.

This attitude differed sharply from what Jones had learned thus far about life and art. He was a first-generation college student raised among migrant workers in upstate New York. He’d grown up watching “standard American fare” on TV and reading the Emily Dickinson assigned in his public high school. Sensitive and closeted, he felt alienated by what he perceived as the militant attitudes of his politically active classmates. He was “uneasy” with their “hurly-burly . . . counterculture,” and with the prevailing notion of art as the “individual pursuit of masterpieces.” Cage’s ideas of “non-intention” floored him. The composer’s disregard for his audience, his willingness “to not be liked,” was at once liberating and soothing. For years, Jones has listened to audio recordings of Cage’s 1958 lecture “Indeterminacy” to relax.

Jones went on to make very different work from Cage’s. He is known for propulsive, emotionally driven dance pieces that address such themes as slavery and AIDS, and often stem from Jones’s personal experiences as a gay black man. He has cast his mother and sisters in his performances. For Jones, artmaking is a way to take personal and social responsibility for one’s place in the world. Self and intention are paramount. Besides that early awakening, then—and one imagines another artist could just as well have alerted Jones to the life of ideas—what does Jones owe Cage?

Jones attempts an answer by tracing the development of a 2012 dance performance he based on “Indeterminacy.” Cage’s lecture consisted of ninety anecdotes about Zen teachings, dinner parties, and mushroom picking, each read over the course of one minute in a random order. In what he calls a “poker-faced plundering,” Jones replaces Cage’s stories with seventy of his own. These tales of loss, absence, frustration, and contemplation cover many areas of Jones’s biography: professional, personal, and ancestral. Writing as Cage did—off the top of his head—Jones ranges from the moving to the mundane. An account of his mother’s trauma at the hands of white neighbors contrasts uneasily with a musing on a favorite vacation spot. On some subjects, the tone is ponderous and angst-ridden. One story reads: “I have been feeling like crying or breaking something. I wonder if this story is better if I don’t explain why.”

Jones incorporated his lecture in a dance performance, also called Story/Time. A series of photographs in the book captures the result: Jones, clad in white, reads seated under a spotlight at a wooden desk, a row of Granny Smith apples balanced on its edge. His troupe of lithe, virtuosic dancers executes sequences of choreography—some, we learn, from past works of Jones’s, some created on the night of the performance—on the stage around him. Although Jones intended to follow Cage’s project to the letter, he retained neither the Geist nor the form of the original work. Jones abandoned a strictly chance-driven structure for one partially predetermined. Certain stories and movements went together, so that each story took on an abstract quality, while the movements in turn seemed to relate, however obliquely, to particular words, phrases, or wisps of narrative.

Jones’s “plundering” seems born of infatuation, not critique. But in two lectures, “Past Time” and “With Time,” Jones describes intense ambivalence about approaching Cage as a subject. His anxiety is due not to Cage’s iconic status, or to the dissimilarity of the two artists’ approaches. Rather, Jones’s affinity encases a “hot core of indignation.” On the one hand, the composer—“theoretician, lightning rod, and giver of permissions”—initiated Jones’s “artistic maturation.” On the other, Cage symbolizes exclusion. Jones “labored so long to be a part of” Cage’s cultural sphere, and still—in spite of his success—feels left out. He does not exactly say white culture and white tradition—his tone suggests something more along the lines of a personal slight, as if the invitation to join his avant-garde peers got lost in the mail—but it’s not far from his mind. “Was there room for someone like me in [Cage’s] milieu?” he asks. The question seems rhetorical. “I never truly had an intellectual home,” he answers himself, “and never will.”

Of course, alienation can result in autonomy; Jones gave himself “permission” to work according to his own rules, exhibiting a single-mindedness not unlike Cage’s own. But Jones seems to want someone—either himself or his role model—to win. “Isn’t art . . . about feelings?” he implores, as if feelings must, in some final analysis, oppose mere form. Certainly, Cage’s insistence on impersonality dovetailed conveniently with his private desire to be uninvolved with public life—reticence was both his privilege and his personal way. (About his own homosexuality, Cage was evasive, even sly.) Jones’s explanatory text, as “confessional” as it is “about ideas,” stands as an impassioned corrective to such an approach. And yet Jones, for all his maturity as an artist, can’t imbricate admiration with ambivalence—and his dutiful stories don’t capture the way Cage haunts his thinking. The anger and veneration don’t mix. They sit side by side, like oil and water.

Lizzie Feidelson is a performer, a writer, and an associate editor of Triple Canopy. Her work has appeared in n+1 and Bomb Magazine, among other publications.