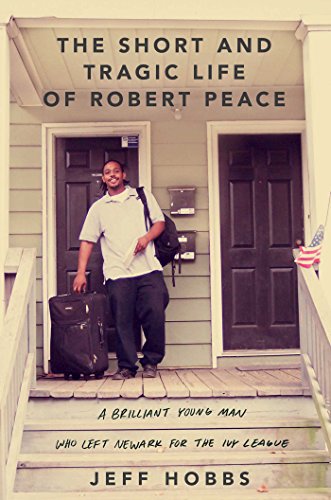

The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace is the work of Jeff Hobbs, a close college friend of the book’s subject, and large chunks are told from his perspective. But if the story has an audience-identification character—someone who asks the questions you’re asking and thinks the thoughts you’re thinking as Peace moves inexorably toward his sad demise in the basement of a drug stash house—it’s Oswaldo Gutierrez, another of Peace’s friends from Yale, who is, as Peace was, a native of Newark.

“With Oswaldo, he would talk about home,” Hobbs writes of Peace. The two shared a growing sense of outrage, though it manifested differently. Gutierrez “found himself angry all the time, judging his classmates and what he saw as their blithe existences, their wide-open futures that didn’t involve taking care of a sprawling, violent, dysfunctional family.” Peace, by contrast, “harbored many of the same feelings but was able to do so seamlessly, with a smile and some profane but harmless shit talk over a blunt.”

In the years after college, Gutierrez would struggle with mental illness and the responsibilities of family. With time, however, he started to move his life forward. And in doing so, he began to see Peace—a man who, despite his brilliance, insight, and Yale degree, couldn’t do the same—as stuck in a dangerous place playing a dangerous game.

“Oswaldo had been there for Rob through all of the experiences that now separated those two versions of the same man,” writes Hobbs. “He could trace the many events and patterns that, though sometimes innocuous in the happening, had accumulated with a rigid scientific surety to produce this man, whose generosity and intelligence were matched only by his flaws.”

Those experiences didn’t merely spring from the inevitable culture clashes and adjustments involved in coming to Yale from much poorer families and neighborhoods than those of many of their peers. Peace and Gutierrez had also grown up in the Newark of the ’80s and ’90s, when a crack-fueled drug trade sparked an epidemic of gang violence and triggered a rapid deterioration of the city’s economic base—conditions all made worse by Newark’s long-standing segregation and concentrated poverty.

Peace was in the middle of this turmoil, insulated from its more immediate hazards by a working-class mother, Jackie, who fought to instill middle-class values in her son, sending him to private schools and living away from the worst parts of Newark. But Peace also remained deeply connected to Newark’s drug scene through his drug-dealer father, Skeet Douglas. Douglas, writes Hobbs, both “presented himself as the tough guy . . . instructing the boy on dirty lyrics and dirtier fistfight tricks, driving Rob around East Orange while giving coded shout-outs to the hustlers,” and “valued intelligence above all,” nourishing the “early manifestations of Rob’s intellect.” Douglas’s arrest and conviction for murder, when Peace was a young child, would shape the rest of his son’s life in subtle ways—even after Douglas had died from cancer. Indeed, the young Peace’s ongoing identification with his father prefigured this scene with Gutierrez: “Rob was asking Oswaldo for drug contacts in Philadelphia, perhaps classmates of his who smoked, so that he could hustle there. ‘Get the fuck out,’ Oswaldo replied. He opened the door.”

Peace was killed not long after this dramatic leave-taking, when several men stormed the East Orange house where he and his friends grew and processed marijuana. No one knew who they were. “They could have been involved with a threatened local dealer, here to make a statement,” muses Hobbs. “They could have been anyone, really, any of the dozens of people, both local and farther flung, with whom Rob worked now or had in the past.”

The glumly anonymous character of Peace’s death highlights an important point in Hobbs’s narrative: Peace’s final downward spiral began with an action destroying the links between his college world and the chaotic and dangerous legacy of Newark. The chronicle of Peace’s life, like all biography, focuses on personal traits of its subject, which reinforce both the brilliant promise of the young man’s future and the tragedy of his death. But just as important, The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace also demonstrates the extent to which individual lives are shaped by remote and impersonal forces. In Peace’s case, the most decisive such force was neighborhood segregation.

As sociologist Patrick Sharkey demonstrates in his 2013 book, Stuck in Place, neighborhood segregation has become deeply entrenched across generations. “Almost three out of four black families living in today’s most segregated, poorest neighborhoods are the same families that lived in the ghettos of the 1970s,” he writes. What’s important to understand is that predominantly black ghettos were, and are, economically diverse places, with poor, working-, and lower-middle-class residents. So, for example, the Peace family, which sought to fulfill one of the basic tenets of the American family mythos by remaining firmly rooted in place, sank into protracted poverty as the traditional sources of economic stability dried up around them. The Peaces lived in Orange (an area outside of Newark) as it transitioned to a majority-black city and stayed on as it became a ghetto. “During Rob’s early childhood,” notes Hobbs, “East Orange represented the second-highest concentration of African Americans living below the poverty line in America, behind East St. Louis.”

One consequence of this segregation, Sharkey argues, is a stark difference in the respective neighborhood environments in white and black communities. “Even if a white and a black child are raised by parents who have similar jobs, similar levels of education, and similar aspirations for their children,” Sharkey notes, “the rigid segregation of urban neighborhoods means that the black child will be raised in a residential environment with higher poverty, fewer resources, poorer schools, and more violence than that of the white child.” The numbers are shocking: 31 percent of blacks born between 1985 and 2000 live in neighborhoods of greater than 30 percent poverty, compared to just 1 percent of whites born in the same period. What’s more, exposure to poverty is a regular feature of middle-class black life in a way that’s unimaginable for most middle-class whites.

This core disparity in childhood experience between the races has profound implications for middle-class black children, as sociologist Mary Pattillo-McCoy reveals in her 1999 study, Black Picket Fences. These children not only suffer from inadequate resources and crumbling schools; they also, unlike their white counterparts, have easy access to criminal networks that can send them abruptly into downward mobility. “Black middle-class youth interact with friends who embrace components of both street and decent lifestyles, and neighborhood adults set both street and decent examples,” Pattillo-McCoy writes.

This dynamic was quite apparent in Jackie Peace’s life—chiefly through her relationship with Rob’s father. It likewise shaped much of Rob’s life, particularly while he was in high school. Faced with sharply divergent peer groups, he mastered a kind of “code-switching,” which allowed him to navigate the mutually exclusive worlds of private school and the street. His facility with the code of middle-class achievement won him admission to Yale—where he continued his academic stardom—as well as the full support of a wealthy benefactor.

So what happened? Put simply, Peace couldn’t control the chain of events he’d set in motion. He could code-switch, but he couldn’t disconnect from the street or the networks he’d built. In college, he used those networks to sell marijuana on a large scale, and as an adult he continued to do so, in hopes of proving himself a master of both worlds. In Pattillo-McCoy’s parlance, Peace was “consumed” by the ghetto—and allowed himself to become steeped in its mores and folkways to the point of disaster.

Still, the casual indictment of the Newark ghetto lets the rest of us off the hook. Peace’s neighborhood didn’t happen by accident. It wasn’t a surprise that Newark and Orange became havens for drugs and violence. Yes, Peace made bad choices and squandered opportunities, but it’s because of public policy—of actions we took to create ghettos like East Orange—that those choices led to the worst possible outcome. Without the redlining that kept capital out of Newark or the housing discrimination that kept blacks in, the Peace family—and Rob—could have had a different, more prosperous life.

The great tragedy at the heart of The Short and Tragic Life of Robert Peace isn’t just Peace’s particular story; it’s the extent to which it couldn’t have happened any other way. It’s impossible to overstate just how completely Peace’s personal missteps were shaped and governed by his environment. He was a product of these neighborhoods. He was a product of us, as a polity. We raised him, we shaped him, and—in the end—we killed him.

Jamelle Bouie is a staff writer for Slate, where he covers politics, policy, and race.