Long before I had any idea that Laurie Colwin was a food writer, I loved her writing about food. I discovered it not in the articles she wrote for Gourmet and other magazines, starting in the ’80s, but in her fiction, each volume of which, if I may borrow one of her titles, is another marvelous thing. They’ve been a part of my life for so long now, in steady rotation on my bedside table and in my brain, that I can’t remember when I read my first one, or even which one it was.

What I do remember, effortlessly, are the meals that animate them. In tales of domestic life, which is what Colwin’s are (in the best sense of that tradition), it’s the day-to-day particulars that provide all the depth. As she writes in a short story narrated by a peripatetic visitor to other people’s country homes, apartments, and dining rooms: “If you are interested in people, their domestic arrangements are of interest, too.” And so we have Polly Demarest, in Family Happiness, who loves her family, her part-time job, and her Park Avenue apartment but is having an affair anyway, bringing a smoked-salmon sandwich to her lover after her extended family’s ritual Sunday breakfast. She’s the good girl of her clan, so her gesture of rebellion is only partially realized: She stops at a deli on the way rather than taking food from her parents’ table. But all indications are that this is just her opening salvo. “Next time,” she announces defiantly, “I’m going to make up a huge sandwich, wrap it in my napkin, and stick it into my bag—right in front of everyone.” Here, food is both a weapon and a token of affection, and only Colwin could pull off that sly but utterly true-to-life contradiction.

Later in the book, the pair meet for lunch at “Sublime Salad Works,” in a scene that displays not just the genius of Colwin’s dry humor but her prescience about the overwrought artisanal-food era to come (Family Happiness was first published in 1982). Polly is a wreck, a state she attempts to remedy by ordering the “Swiss Health, which was described on the menu as ‘A life-affirming medley of low-calorie Swiss cheese, a piquant julienne of hearty beet, tender carrot, and powerful high-energy dressing.’” When a colleague of Polly’s comes in and sits, awkwardly, with the ersatz couple, this little masterpiece of socioculinary slapstick ensues:

“I’d like to order,” Martha said. “What can I get fastest?”

“Our salads are all handcrafted,” said the waitress.

“Bulgarian Eggplant Salad,” Martha said, “and a cup of coffee right away unless the coffee is handcrafted, too.”

“I didn’t get that,” the waitress said.

“Yes, you did,” said Martha. “Bulgarian Eggplant and a coffee. Just because you went to a progressive high school and studied modern dance at college doesn’t mean you can’t remember a simple order.”

“How did you know that?” the waitress asked.

“A child could tell,” said Martha.

This is Colwin’s world: middle-class, urban, filled with flawed, lovable, intelligent people. Many of her characters, I suspect and others have speculated, are drawn from her own life in ’70s and ’80s Manhattan, where she was young and single and working in publishing, then married to a publisher and the mother of a little girl. Always, she was a whirlwind of social energy and words—“a deus ex machina with aggressively curly hair,” as Anna Quindlen put it in one of the many tributes written to Colwin since her death in 1992 at the age of forty-eight. Her books don’t present us with anything particularly profound, except, perhaps, the idea that happily married people can be unhappy, which is no doubt still news to certain readers. Their appeal is in their characters’ chronic inability to do things the easy way, which, of course, mimics our own. (Polly hasn’t given up her affair by the end of Family Happiness, and much to her own surprise, she doesn’t seem likely to; the fakery of simple closure was clearly not for Colwin.) Unlike her food books, in which Colwin herself is always the main character and the anecdotes she tells are instructive as well as entertaining, her novels and stories offer ample room for cooks, non-cooks, aspiring cooks, pets, and everyone else, too. The writing is frank about the confusions of being an adult, and just a little bit light, providing a gentle entrance into the inevitable understanding that no matter how delicious the food or heavy the silver, there’s usually something nasty, or at least hard to see, lurking under the table.

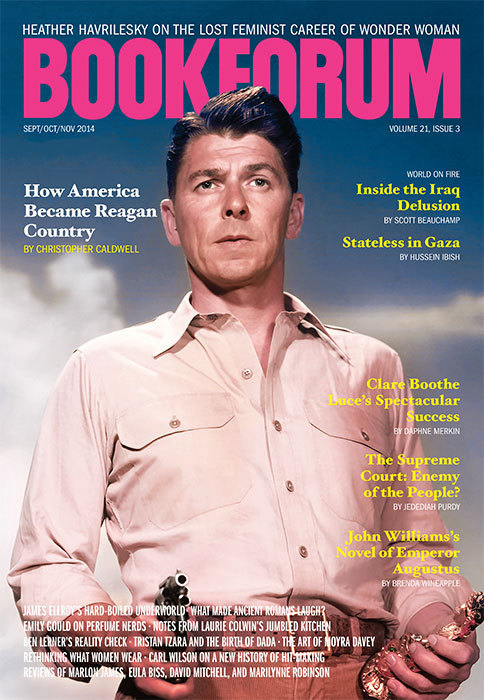

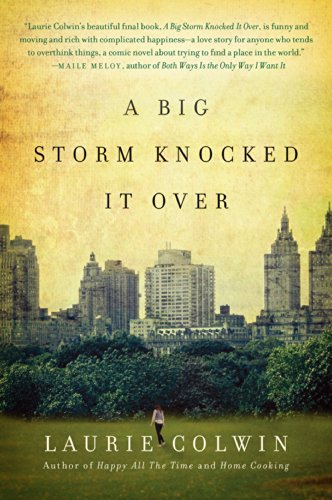

None of which is to say that Colwin didn’t know a lot about what to put on the table. She published a collection of recipe columns, Home Cooking, in 1988; a second one, More Home Cooking, came out posthumously in 1993. The latter has just been reissued, along with my favorite of her novels, A Big Storm Knocked It Over (also published in 1993), which, in addition to including a character who bakes over-the-top cakes for New York’s wealthiest narcissists, deftly skewers the publishing industry.

The two food books, which I got around to reading after I ran out of novels and stories, have never lacked for an audience, but their time has come again. Colwin’s recipes pop up more and more often on food blogs, accompanied by rapturous praise for their creator, and last spring a New York Times reporter attended a Colwin-themed dinner hosted by members of “a young, literary, food-obsessed crowd,” who were still in grade school when Colwin passed away but delight in her nonetheless. Reading the columns again, it’s not hard to see why: She’s right there on every page, and she’s fantastic company, every bit as hilarious and spiky as her fictional characters. Among her most famous essays is “Alone in the Kitchen with an Eggplant,” which opens with these lines: “For eight years I lived in a one-room apartment a little larger than the Columbia Encyclopedia. It is lucky I never met Wilt Chamberlain because if I had invited him in for coffee he would have been unable to spread his arms in my room.” That this beloved piece doesn’t even really include a recipe has never been a sticking point, as it’s actually about something much more important to any reader-cook: the necessity and pleasure of temporarily escaping back into single life by cooking an old familiar meal all alone. (As Colwin puts it, “Certainly cooking for oneself reveals man at his weirdest.”) If you have yet to read Colwin’s food writing, I’ll list just a few more titles that hint at the treasures that lie ahead: “Stuffing: A Confession”; “Bread Baking Without Agony”; “Desserts That Quiver”; “Repulsive Dinners: A Memoir”; and “Easy Cooking for Exhausted People.”

Unlike many Colwin devotees, I’ve never used one of her recipes. There are those who swear by her brownies (which use the same recipe as Katharine Hepburn’s but nonetheless seem deeply Colwinesque), or her method for frying chicken, or her tomato-and-corn pie, and I salute them. My feeling, though, is that I have other places I can find methodology. What I can’t find elsewhere is someone who discusses, alongside a recipe, how much she loves to give dinner parties but is also a little cranky about them. To wit:

Some people have been taught that it is impolite to turn anything down, and if you ask them, they say: “Oh, I eat everything.” Then, as you are slicing the steak, they shyly tell you that they have not eaten red meat in ten years. . . . It is also wise to know if people are fatally allergic to something. . . . You do not, of course, want to be responsible for the death of your guests, but sometimes it seems that they will be the death of you.

I like Colwin’s food writing very much, but it’s her novels that I go back to again and again. Her intricate worlds—full of people who lovingly revolve around one another, with occasional pit stops in their kitchens, dining rooms, and local coffee shops—have been a refuge from my own overcomplicated life more times than I can count. Somehow, witnessing other people, even made-up ones, doubting and blundering their way through what is plainly happiness, even when they can’t see it themselves, makes me feel better about my own tendency to do the same. That most of them really like to eat is an added benefit.

“She was a great cook,” Juris Jurjevics, Colwin’s husband, told the New York Times. “But the fiascos were kind of fabulous.” She was an even greater novelist, and her humane explorations of uncertainty are perfect—not a fiasco among them.

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).