THE FIRST TIME I SAW Gabriella Coleman speak about the hacker group Anonymous I was befuddled. It must have been around 2009. Anonymous was already at least three years old, having materialized out of the bowels of the popular, and often excruciatingly obscene, online bulletin board 4chan as early as 2006, yet it was still known mostly for its antisocial pranks. One particularly troubling stunt was fresh on people’s minds: Some exceptionally reprobate Anons had boasted of uploading rapidly flashing images to an epilepsy support forum in order to trigger seizures in viewers. In her talk, Coleman acknowledged that Anonymous included a bunch of “trolls”—online miscreants devoted to inspiring frustration and misery in others—but insisted there were members driven by more benevolent motives. Anonymous, she passionately argued, possessed the capacity to employ the trickster spirit to positive effect.

From my vantage point, there didn’t seem to be much evidence of that, except, perhaps, the group’s ongoing campaign against the Church of Scientology. When a ridiculous recruitment video featuring Tom Cruise was leaked on YouTube, Scientology officials went berserk trying to erase it from the Web. So Anonymous spread the video and launched attacks against Scientology websites, overwhelmed Scientology offices with prank calls and black faxes, and even organized an international day of street demonstrations against the church. Anonymous’s counteroffensive was certainly amusing—who doesn’t want to see Cruise and his cult-pushing buddies taunted, if not taken down?—but I assumed it was a one-off. However intrigued I was by Coleman’s thesis, I couldn’t relate to her enthusiasm, nor did I trust her conviction.

But as an anthropologist deeply embedded in the Anonymous community, Coleman could discern things that were invisible to casual observers. These other facets of Anonymous only began to come into focus for me on the first day of the Occupy Wall Street demonstrations. As I mingled with a small group in Zuccotti Park, I was surprised to see Anonymous vigorously promoting the encampment. Whatever you thought of the protests, Occupy was hardly a cause that a bunch of nihilists (a common view of Anonymous) or die-hard libertarians (a common computer-nerd stereotype) would rally behind. I started to pay more attention.

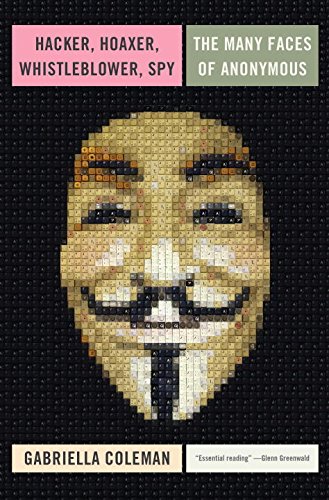

As the subtitle of her epic and excellent new book, Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy: The Many Faces of Anonymous, suggests, Coleman’s subject is mercurial. The group’s ethos of “motherfuckery” (a commitment to mayhem) coexists alongside what some less politically engaged Anons derisively call “moral faggotry” (a devotion to social and political causes). As a result, Anonymous is a remarkable, if confounding—and yes, occasionally noxious—witches’ brew, into which a wide variety of human characteristics have been poured: cruelty, sexism, homophobia, racism, immaturity, and idiocy, but also intelligence, idealism, ingenuity, and even courage.

This perplexing concoction is conveyed in the definition of “lulz” Coleman quotes from the online Encyclopedia Dramatica (if you haven’t come across the site before, imagine a satirical and self-referential, meme-obsessed Wikipedia on acid). Like any subculture, Anonymous has its own jargon and value system, and lulz hold a central, and even paramount, position in its lexicon. “Lulz is a corruption of LOL . . . signifying laughter at someone else’s expense,” the encyclopedia helpfully explains. “Lulz is engaged in by Internet users who have witnessed one major economic/environmental/political disaster too many, and who thus view a state of voluntary, gleeful sociopathy over the world’s current apocalyptic state, as superior to being continually emo.” Some readers might get stuck on the phrase “gleeful sociopathy”—which emphasizes a terrifying lack of conscience—but, for me, what stands out is the sensitivity that contributes directly to this affect. Lulz are not purely aggressive and contemptuous; they are, perversely, rooted in disappointment and righteous indignation. Like the return of the repressed, the emo (short, of course, for “emotional”) element persists and resurfaces, suffusing much of the activity that has put Anonymous on the cultural map in recent years.

The story of Anonymous’s emergence and transformation into one of the most intriguing and, arguably, potent leaderless political collaborations of our time has been told before in books such as Parmy Olson’s We Are Anonymous; in the 2012 documentary We Are Legion; and in a spate of glossy magazine articles. Coleman’s history complements, and frequently corrects, these popular accounts, but the book’s comprehensive detail and deep analysis set it apart. She covers the history of hacking and trolling, revealing the various tech-savvy and humor-loving milieus that spawned Anonymous. She traces the group’s political turn, from the battle with Scientology to actions like “Operation Payback,” which targeted PayPal and other financial institutions for cutting off WikiLeaks, and OpTunisia, which assisted antigovernment protesters during the Arab Spring. Coleman continues her tale as Anonymous fragments, tracking the evolution of spin-off cadres such as LulzSec and AntiSec and the rise and fall of well-known figures like Barrett Brown, Jeremy Hammond, and the double-crossing Hector Monsegur, aka “Sabu.”

Through it all, Coleman charts her own conceptual course, breaking with the standard narratives, particularly the click-baity cautionary tales about the dangers of Anonymous. Her book offers its share of warnings, but ones more nuanced, compelling, and empathetic than the typical hand-wringing about online mobs and the conundrum of virtual vigilante justice. Coleman is no cheerleader: She questions the wisdom of the hive mind, registers her ambivalence about the supremacy of lulz, and is appropriately mortified by some of the queasier trolling exploits she recounts. But she also doesn’t wag her finger from some imagined high ground, in part because she could be considered an Anon herself. Coleman repeatedly crosses the line between observer and participant, engaging in conversations, helping with media outreach, and editing manifestos, and this inside view is part of what makes the book unique. By becoming part of the clan, Coleman provides evidence of another one of her key points: Anonymous is surprisingly diverse. While mostly male dominated (though some female Anons do rise to prominence), Anonymous is multigenerational and multiethnic. Some high-profile members were revealed to be teenagers, like eighteen-year-old Jake Davis, aka “Topiary,” and Mustafa al-Bassam, aka “tflow,” while others are grizzled social-movement veterans, like the colorful Christopher Doyon, aka “Commander X,” who is currently on the lam in Canada.

Instead of lingering on Anonymous’s ethical and tactical lapses, which have been thoroughly dissected in the press, Coleman focuses on the larger social and political context, rightfully raising red flags about the government’s overblown response to the purported hacker menace. An alarming double standard applies to digital protests: While offline civil disobedience or vandalism—think blocking an intersection or defacing a corporate billboard—often leads to nothing more than a slap on the wrist, felony charges are distressingly common for hackers due to the powers granted zealous state officials by ill-conceived legislation like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act. The ongoing crackdown has been called a “nerd scare,” with more than one hundred people arrested around the world in connection with Anonymous. Many of these individuals did nothing but partake in distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks—in other words, they pressed a few buttons to help flood a website with traffic—which, as Coleman points out, hardly qualifies as hacking. And some didn’t even do that much.

But, you may be thinking, orchestrating a DDoS attack is nothing like a sit-in! And isn’t it ironic, you might continue, that a group known for fighting censorship impinges on the free speech of others by causing their websites to crash? Coleman reveals that these and countless related questions have already been debated at length within the Anonymous community. Indeed, one of the book’s most compelling revelations is that every common criticism of Anonymous has already been vigorously taken up by Anons: They have railed against the limitations of social media and affirmed the superiority of offline protests; they have complained about the puerile nature of specific operations; they have vehemently denounced “doxing”—i.e., outing—individuals in the absence of irrefutable evidence of their crimes. Anonymous, so one saying goes, is not unanimous. The group’s often raucous culture of dissension and debate, and the serial improvisations of democracy that grow out of it, all come to life here through extended chatlog excerpts elucidated by Coleman’s engrossing and convivial commentary.

As Coleman shows so well, Anons are irreverent and intelligent—and also impatient. And why shouldn’t they be? They want to provoke a response, this instant, and to play a part in exposing corruption and challenging power. That they do so by submerging their individuality in a collective identity is particularly notable in an age of personal branding and incessant self-promotion: Pursuing individual celebrity, Coleman writes, is the “ultimate taboo.” (Thus does Sabu rail against “those that want fame” and “infiltrators,” right before he’s exposed as an attention-seeking FBI informant.) They are, arguably, the last refuge of a hard-core, underground punk ethos. Coleman returns again and again to Anons’ penchant for heaping scorn on those who use collective endeavors to gain individual notoriety, yet she also acknowledges that a few highly visible characters often contribute disproportionately to the cause.

By examining these sorts of tensions, Coleman offers suggestive insight into the relationship between the networked-attention economy and political activism. Anonymous, like Occupy and various other grassroots campaigns, has been able to cast an enormous virtual shadow, but ubiquity can be a double-edged sword. What’s the true utility of clicks and retweets if people just get distracted and move on to the next thing? Does the emphasis on spectacle only tighten the media’s grip on activists and increase their dependence on both traditional news outlets and digital corporate platforms? How can a group capture online attention and transform it into sustained and effective political pressure? These issues keep my comrades and me up at night.

As honest as some Anons are about the limitations of their methods, the government and military-defense contractors are still committed to inflating the group’s prowess and the danger it poses, propping up an enemy to justify their ever-expanding budgets and purview. How threatening are these Anons, actually? Not very, it might seem, but that’s not the point. Government and corporate outcry against hackers is really about mind games and maintaining power not cybersecurity. In 2011, Anonymous obtained PowerPoint slides from the security firm HBGary detailing a plan not just to spy on and disrupt WikiLeaks but also, crucially, to defame and intimidate supporters and journalists. These allies have a “liberal bent,” the firm noted, but “ultimately most of them if pushed will choose professional preservation over cause.”

In the end, Hacker, Hoaxer, Whistleblower, Spy offers an extended and persuasive argument for defying HBGary’s cynical assessment and siding with the hackers, professional preservation be damned. While most Internet users are busy looking at cat videos or porn or frittering away time stalking their frenemies on Facebook, some young people might be logging on, debating right and wrong, and getting hooked on political action thanks to Anonymous. Maybe such experimenters will become lifelong activists, or maybe they’re just looking for lulz. Sure, their operations haven’t always been pretty, but no social movement is perfect or pure. Few, however, have been as unpredictable, outrageous, and entertaining as Anonymous. To my mind, that’s reason enough to join Coleman in rooting for them.

Astra Taylor is a filmmaker, an activist, and the author of The People’s Platform: Taking Back Power and Culture in the Digital Age (Metropolitan Books, 2014).