STORIES THAT MAKE YOU FORGET EVERYTHING ELSE

LYDIA DAVIS

For many years now, I have admired Lucia Berlin’s stories out loud to people, but almost no one has known her name or her work. This has been an abiding mystery to me. Is it geographical—the places she lived, wrote about (Alaska, Chile, Colorado)? Or is it her difficult subjects—alcoholism, poverty, abandonment, cruelty? But she also wrote about love, generosity, loyalty, courage, and many other good things. And she was always funny. As one of her narrators says, “I don’t mind telling people awful things if I can make them funny.”

She should be better known because she is such a good, economical, colorful, large-hearted, witty writer, and because so much actually happens in her stories—it is almost impossible to stop reading once you begin. They are stories that make you forget everything else—what is happening in your own day, where you are, even who you are.

I have trouble giving a single answer to a question that has the word best in it: Best sentence? Best ending? Best book? There are so many superlative sentences, endings, books—and they are all different, and can’t be compared. But certainly one of the best—most natural, yet most artful—storytellers is Lucia Berlin, and Where I Live Now, a volume of stories published by Black Sparrow Press back in 1999, is a book to beguile a long afternoon, full of pathos and wit as every book of hers is.

Lydia Davis is the author of Can’t and Won’t (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014).

A TRIANGULAR LOVE STORY IN 1960S LONDON

SIMON REYNOLDS

Fred Vermorel has achieved both renown and notoriety for his unorthodox approach to pop biography and for his scabrous theories of fame and fandom. But Vivienne Westwood: Fashion, Perversity and the Sixties Laid Bare (1996) was his most eccentric statement. For a start, the book was as much about Westwood’s partner, Malcolm McLaren, as the legendary designer herself. Westwood’s story was ably chronicled in an imaginary interview weaved together from magazine quotes and half-remembered anecdotes from Vermorel’s long association with the punk-couture duo and the Sex Pistols’ milieu. But the book really came alive in the central section: Vermorel’s memoir of 1960s London, where he and McLaren were art-school accomplices. The longest and most vivid part of the book, it’s packed with fascinating digressions on topics such as the semiotics of cigarette smoking and the atmosphere of all-night art-cinema houses. Among Vermorel’s provocative assertions is that pop music simply wasn’t as important back then as it was made out to be by subsequent memorials to the ’60s, but instead was regarded as unserious, a mere backdrop to other artistic activities. Posing as a profile of a fashion icon, Vivienne Westwood presents the reader with an outlandish blend of cultural etiology (it doubles as both an autopsy of the impossible dreams of the ’60s and an analysis of that decade’s perverse psychology) and a triangular love story. Vermorel and Westwood both emerge as still besotted with the incorrigible McLaren, despite each having “broken up” with him long ago.

Simon Reynolds is the author of, most recently, Retromania: Pop Culture’s Addiction to Its Own Past (Faber & Faber, 2011).

A MISGUIDED AND PASSIONATE QUEST

CHRIS KRAUS

A cofounder of the New Narrative movement, Robert Glück is perhaps best known for his first novel, Jack the Modernist (1985), which became the ur-text of postmodern gay fiction soon after its publication. His 1994 novel, Margery Kempe, is also stunningly good but less well known. I read it twenty years ago and still remember whole lines. Poetic, bold, and precise, the book fuses the misguided and passionate quest of the fifteenth-century mystic Margery Kempe with Glück’s obsession with his elusive boyfriend, the younger and aloof “L.” It is a little-known late-twentieth-century classic, counterpoising sexual mores in the wake of the AIDS epidemic with the devastation of the European countryside at the end of the Hundred Years’ War. Glück is an acute and unsentimental observer of gestures, botany, skies, and cuisine. He captures the feeling and flow of the late Middle Ages, when “mobility and chance were beginning,” and brings that world close to his own. Margery Kempe, the mystic, was the author of (arguably) the first autobiography, The Book of Margery Kempe (1436), an account of her trials. Margery fails as a mystic because her love for Jesus is tainted by vanity; Bob adores L. for the same qualities that wound him the most. Glück brilliantly locates the (New Narrative) impulse toward first-person narration in time and despair. He observes the turning of centuries. As he writes, “Margery steps into modernity so empty she needs an autobiography.”

Chris Kraus’s latest novel is Summer of Hate (Semiotext(e), 2012).

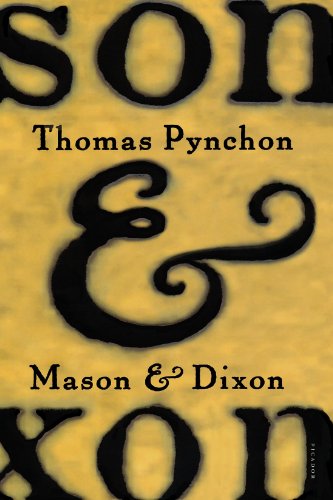

NEW FORMS OF COMIC THINKING

ADAM THIRLWELL

Thomas Pynchon’s Mason & Dixon might seem a strange choice for an underrated book, since on publication in 1997 it was feted and adored, but I have a melancholy feeling that it now exists, here in 2014, as a loved but ignored invention, like Vaucanson’s mechanical duck (which has its own zany part to play in the book’s ragamuffin plot), whereas Pynchon’s novel should be constantly examined and revered. But then, to be a masterpiece is a lonely fate. And here it is, a masterpiece written in Enlightenment English, with its occasional contemporary grace note, like the moment when, in a bar, a sailor interrupts an intellectual debate with the translation of a difficult Hebrew passage: “That is, ‘I am that which I am,’ helpfully translates a somehow nautical-looking Indiv. with gigantick Fore-Arms, and one Eye ever a-Squint from the Smoke of his Pipe.” This helpful sailor, obviously, is Popeye. Mason & Dixon allows different eras to sift through the sieve of Pynchon’s style, and as you keep reading you gradually realize that all the usual duos—history and fiction, realism and fantasia, culture and barbarism—are being dissolved. It develops new forms of comic thinking. Which means that we should all be rereading it, this historical artifact, if we want to make any kind of literary future.

Adam Thirlwell’s new novel, Lurid & Cute, will be published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux in 2015.