Until recently, Hollywood was the most famous American place in the world. Over the past decade or so, it’s been dethroned by Brooklyn (“Are you from Brooklyn? Do you like Interpol?” is what you are likely to be asked on Air France) and, of course, the World Trade Center. Still, third place is nice. Hollywood is a terrific and justifiably iconic American thing. It’s served ever since its founding as a cultural capital of sin as well as a focal point of American anti-Semitism.

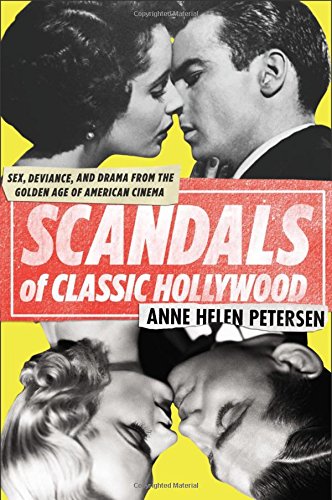

Two new books examine the great gossipy early days of Los Angeles as industry town: William J. Mann’s Tinseltown: Murder, Morphine, and Madness at the Dawn of Hollywood (Harper, $28) and Anne Helen Petersen’s Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema (Plume, $16). They share not just a love for the serial comma but also sympathetic portrayals of poor Fatty Arbuckle, the silent-era comedian who was forced to endure three trials for the murder of a partygoing lass in the early 1920s. Even though he was ultimately exonerated, he was ostracized from the film industry for the rest of his life.

While Scandals goes wide, ending with James Dean (no, not the porn star), Tinseltown limits itself to the ’20s and purports to solve the murder of director William Desmond Taylor, whose body was discovered by his big gay manservant in 1922. Three women were considered suspects—or, if nothing else, motives: Mary Miles Minter, an obsessed and lovesick drama teen; Margaret Gibson, a hard-eyed schemer; and druggy good-time girl Mabel Normand. All three would be undone in the aftermath. Only one, we are eventually told, actually knew how Taylor died.

In Mann’s telling, the era was rife with dangerous abortions, prostitution, cocaine, illegal alcohol, and oodles of lying about one’s age and/or name, unlike now. (Taylor’s real name was William Deane-Tanner, it turns out.) Starlets would get coked up in order to bring themselves to sleep with Samuel Goldwyn with only a stillbirth for their troubles. There were cunning valets and con men galore.

The industry was beset on all sides by busybodies. There was New York City’s staunch sin-hating cop Ellen O’Grady, who wanted to shut down the filth in Times Square but was forced out of the police department by influence-peddling industry interests. There was the Lord’s Day Alliance, which wanted to protect America from the devil (read: Jews) in Hollywood. The producers banded together and announced they would renounce licentiousness; they did not. Eventually they hired William Hays to police their product, and ever since then Hollywood has been whistle clean.

Tinseltown may well be the most completist murder mystery of all time, and so its attempt to gin up suspense can be rickety. Pretty much every chapter ends like this: “Everybody in Tinseltown had secrets. But few had more than William Desmond Taylor.” Still, Mann’s got the goods, and we can forgive the staginess. (Among Taylor’s bigger secrets: He had a family that he’d abandoned and a boyfriend. This is one of those true-life plots that would look purple on Mad Men.)

Indeed, it’s the reliance on “goods” that makes these books unusual and special. Both lean on fact and history instead of the techniques of literary analysis, which is a sweet relief. The vogue for media studies and the allied focus on produced fictional texts have had great uses over the last few decades. But media studies also encouraged its practitioners to stop caring about facts. Its only aim was to derive information from forms—e.g., narratives, tropes, symbols, and the like. The careful tracking of “representation” within a given genre or text also tended to discount the impact of capitalism. It didn’t matter so much how and why things were made. That filthy inquiry belonged to history and sociology and maybe economics. To the media-studies crowd, everything was just a text, floating there by some means or other.

Of course, both these books overcorrect by virtue of their shared fixation on “scandal.” The problem isn’t so much that our entertainment colossus doubles as a great manufactory of moral licentiousness; it’s that the gaudiest features of our eye-chasing industries are just heightened renditions of the same excesses in our money-chasing ones.

Which is pretty much as it should be. In her day job at BuzzFeed, Petersen—who, I should disclose, is a pal of mine—has argued that we must closely attend to TV and its cultural power because “no medium better encapsulates our ideological moment, day in and day out.” This seems exactly backward. TV is a trailing cultural indicator—perhaps the greatest such monitor of our values that we have, but it’s a far cry from their main progenitor. Television programs—and films and print media—exist for a few reasons, but the primary one is to make money. Television and film’s job is to guess second, and a great deal of cash rides on that guess, as it has from the ’20s onward. As both Mann and Petersen have copiously shown, the guesswork reaches its most profitable heights by plying two basic reflexes: our prurience and our desire to be shocked scolds. Not much has really changed since the days of Zukor and Hearst—except that nowadays people usually get in trouble when they blame everything on the Jews.

Choire Sicha is the author of Very Recent History (Harper, 2013).