“THE ONLY REASON for the existence of a novel is that it does compete with life”—thus spake the Master, Henry James.

Memoirs are different from novels, since they don’t, supposedly, compete with life but are apposite to it, augmenting it interpretively. They are based on experience, and experience needs examination and reflection. The uncommon memoirist presents actualities honestly and imaginatively. To be honest doesn’t require unfailing accuracy, since memory and POV intrude upon reminiscing. Honesty avoids deliberate falsehoods. Honesty means the writer will not be self-serving, not always at the center, not always the star, though always in the movie. Sometimes she picks herself up off the cutting-room floor.

Because the imagination is regularly attached to make-believe, these days it is rarely attached to the writing of memoirs, which are expected to be “true,” that is, factual. But truth and true are not the same as fact. Historians use facts to support their interpretations of events; they draw conclusions based on evidence that is agreed upon by other historians. A memoir’s evidence emerges from memory, the ur–unreliable narrator.

The reader might remember “the scandal” about James Frey and his memoir of drug abuse and rehab, A Million Little Pieces. His agent hadn’t been able to sell it as a novel—it was based closely on his life—and asked him to call it a memoir. Editors wanted memoirs, not novels. He agreed. Oprah Winfrey had him on her show; the book became a best seller. When it was discovered that it was “fictionalized,” Oprah brought him back and shamed him on TV, his editor Nan Talese sitting next to him. It seemed to me something like a Salem witch trial.

Oprah asked: Did your girlfriend commit suicide? Yes, Frey said. Did she hang herself, as you wrote? No, he said. Oprah opened her mouth wide, in horror. The manner in which Frey’s girlfriend killed herself was different, making what he wrote, to many, a terrible lie. But memoirs have always been fictionalized, liberties taken: They are representations, written things, composites; they are reimagined. If all memoirs were examined as Frey’s was, most would be revealed to have fabrications.

Anyone writing is writing in the present—thus spake Gertrude Stein. The return to a distant past will be obscured by a thick crust of time. Looking back, into, and under, writers hope to unearth their pasts. The honest memoirist doesn’t pretend to do anything other than remember. Images might pop up, scenes and faces in bits, in shreds of information. The writer fills sentences with these bits, joining what might have been disparate then but flows together now, in the mind, with the aid of the imagination. It helps select words to carry forward temporally what might be unimportant to others, since it’s not their life. There is invention, always, in doing that well.

A good memoirist must also find meanings outside herself, beyond the limits of subjectivity: For personal memories to count, they will not only be written with emotional vividness, retrospective vision, and intelligence, they will also reach for truths others can inhabit.

Countless memoirs have been published, especially in the past twenty years, but many won’t count in the ways I’m suggesting. While individuals are products of their time, and personal life is intertwined with public life, the body politic, many writers can’t see the forest for the tree. They are incapable, in their retellings, of elucidating more than themselves, and even that sometimes inadequately.

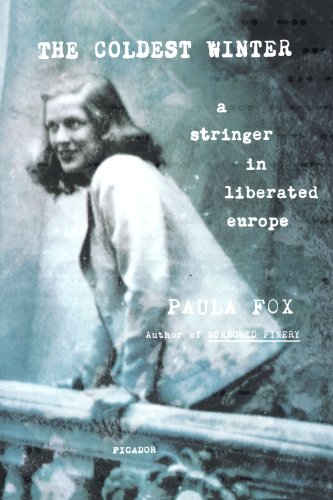

I reviewed Paula Fox’s book The Coldest Winter (2005) almost ten years ago. The portraits and impressions Fox created haunt me still.

Fox traveled to Europe in 1946, the year after World War II ended. She was very young, on her own, living on what she earned. Fox became a stringer for a newspaper based in England, and reported from places devastated by war. And not only physically, with buildings destroyed, which is how the ruins of war are often depicted. Fox renders that too but in this way: “Everywhere I went, I sensed the tracks of the wolf that tried to devour the city.” Her emphasis, focus, and thought are on war’s psychological ruins.

Fox listens to other people’s stories. They and their stories have become part of her experience of life. She writes about a peace conference she attended and a Hungarian boy of nineteen who was also there, oddly, as he had been a member of a fascist youth organization: “He didn’t speak of Jews or Gypsies or homosexuals but only of executions he had witnessed, as if they had been the romance of his life. . . . I pitied him for his starved look, for his youth. But I hated him too.”

She writes of a midwestern American, Mrs. Helen Grassner, who travels to Warsaw on behalf of a Jewish women’s organization. “Suddenly I felt uneasy. Mrs. Grassner, whom I had had the presumption to regard with a certain unthinking tolerance, had escaped my definition of her. She was as large as life.” Fox demonstrates the illusion of first impressions, and honestly reflects on the workings of prejudice in herself.

In The Coldest Winter, Fox’s acute observations, her exquisite ability to re-create what she saw and heard, produce withering, beautiful, frightening portraits and uncanny descriptions of mood and place. She renders credible and complex characters, using her gifts as a novelist, and enables readers to feel intimate with people from long ago, from a terrible time. They live again, these people, bad, good, Fox reminding us that what is lost in war is life.

Lynne Tillman is the author of five novels, most recently American Genius: A Comedy (Soft Skull, 2006). Her essay collection What Would Lynne Tillman Do? (Red Lemonade) was published earlier this year.