Photography has recognized only a few prodigies during its history. Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894–1986) was certainly one of them. The action shots he took before the age of twelve—of early French car races, experiments with manned flight, a cousin leaping down the stairs—have seldom been equaled. Alvin Langdon Coburn (1882–1966) was another wunderkind. He could handle a 4 × 5 view camera when he was eight and was exhibiting with Frederick Evans and other Linked Ring artists at eighteen. Francesca Woodman (1958–81) began her series of self-portraits in earnest when she was fourteen, and her intense productivity did not stop until her suicide at twenty-two.

Stephen Shore (b. 1947) is perhaps the best current example of a photographer who did absurdly sophisticated work at an absurdly young age. He was ten when a neighbor gave him a copy of Walker Evans’s American Photographs (1938), a difficult book for even an adult to comprehend but one that Shore credits with guiding his austere taste forever after. By age fourteen he had sold three photographs to the Museum of Modern Art (New York), and a year later the museum acquired two more. At eighteen he met Andy Warhol, who invited the Upper West Side schoolboy to bring his cameras downtown to the Factory whenever he wanted, visits (1965–67) that produced an incomparable group of pictures of that notorious scene. Teenage Stephen even helped to light the first performances by the Velvet Underground.

Finally, at the age of twenty-three, he was given a solo show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), only the second living photographer to be so honored and, to this day, still the youngest. What distinguishes Shore from the other freakish talents noted above is that he was just getting started. Had he died at the time of his Met debut, in 1971, he would likely be a historical footnote; instead he became one of the most influential color photographers of the twentieth century.

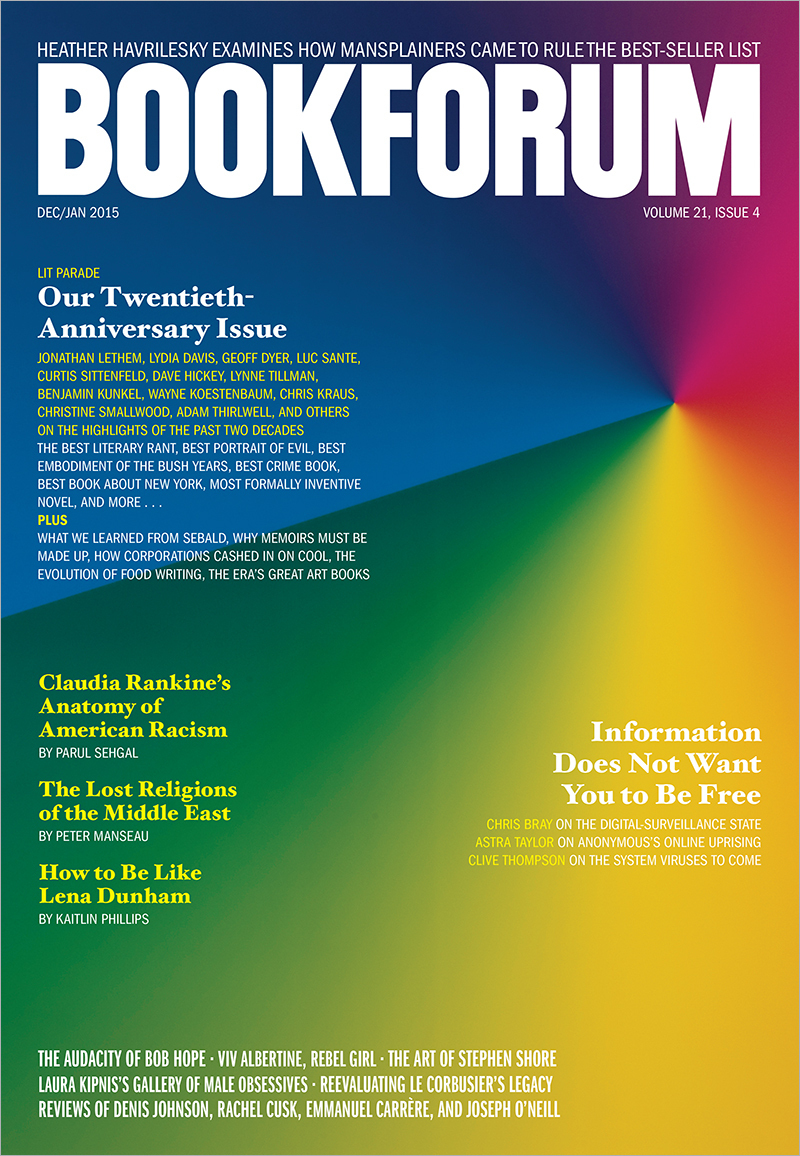

This substantial catalogue, published by Fondación Mapfre/Aperture, is—surprisingly—the first to explore Shore’s remarkable life and career in depth. The selection of 250 images spans six decades and includes his rarely exhibited black-and-white work: New York street pictures, including a gritty bunch from the mid-’60s and a more stately one from 2002; nature studies in Essex County, New York, taken in 1990; and a portrait from Luzzara, Italy, taken in 1993. There are chapters highlighting his familiar style in color with a view camera—Ukraine and Arizona landscapes—as well as one on his embrace of digital print-on-demand technology. (He has so far made eighty-three books using iPhoto.)

But the bulk of the plates and writings here are devoted, rightfully, to the ’70s, when Shore completed two exceptional projects, “American Surfaces” (1972–73) and “Uncommon Places” (1973–81). It is hard to imagine them as products of the same artist, so antithetical do they seem in how they are organized and in what subjects they memorialize. The former is a jumpy hodgepodge of snapshots that strive to top each other in laughable banality; the latter smoothly examines the social landscapes of small towns and cities in patient, luxurious detail. Each project in its own way rubbed against the grain of art photography at the time. Both are documentary catalogues of the American road—of that underrated native invention, the motel, and our behemoth car culture as it was stalling out—and they continue to guide the photographic practices of young artists here and around the world.

For those who prefer to see Shore as a Conceptual or Pop artist, the “American Surfaces” series is the peak of his achievement. A photographic diary of his road trips around the country between March 1972 and December 1973, it marked one of his first journeys into America beyond New York City. (His was a cultured Jewish upbringing in which his parents took him to Europe every year and never thought it necessary that he learn to drive.) To record his mundane activities, and those of his raffish friends, Shore used a Rollei 35, which has a flash unit mounted on the bottom. “The shadow is cast upward,” he explains here in an interview with the British critic David Campany. “It has this weird, almost Cubist quality.” In their crude serialism, Shore’s snapshots from the road are more Ed Ruscha than Robert Frank. No one image carries more emotional weight than any other. A motel toilet equals a grilled cheese sandwich on a diner plate or a woman’s back or a carton of milk or a dog lying on the floor or a fluorescent light fixture on an Acoustile ceiling.

To many in New York’s fine-art-photography crowd, where Shore was a member in good standing, this slapdash approach to craft was an insult. In 1972, Light Gallery in New York exhibited about two hundred of these Kodak drugstore prints to widespread confusion and disdain. The show’s installation did not help: Snapshots were taped to the wall and stacked in a triple-rowed grid that wrapped around three walls. “There was no reverence in the presentation,” Shore recalls. (The Met curator Weston Naef was one of the few enthusiasts, buying the lot.) Shore had to wait for the younger generation—Nan Goldin and Wolfgang Tillmans, to name just two—to realize how much his example had done to liberate art photographers. He deserves some credit, and blame, for the fact that everyone on Facebook and Instagram feels so free to document all aspects of their lives without judging the results too harshly. And the impact of this work on the art world has only increased since 1999, when “American Surfaces” was finally published as a book. (The essay here by the Spanish curator Marta Dahó links the “American Surfaces” project with Ruscha and suggests that Shore’s black-and-white photos of unmonumental Israeli archaeological sites have a kinship with Warhol’s use of banal repetition and with Robert Smithson’s Earthworks, with time being a formal element in both.)

“American Surfaces” was born from Shore’s hearty participation in New York’s Conceptual and Minimalist scenes in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Earlier projects shared some of its egalitarian qualities. In 1969 he had photographed a friend at thirty-minute intervals over the course of a summer day and arranged the prints in a grid. In 1971 he curated “All the Meat You Can Eat,” an exhibition in a SoHo loft he papered with a riotous mix of found imagery: posters, tourist postcards, family memorabilia, porn, police photos, formal portraits of politicians and pets. For a 1971 series, “Greetings from Amarillo. Tall in Texas,” he had a professional printer make postcards of “monumental sites” around the Panhandle city, which he had photographed on a trip in 1969. On later visits he slipped these fake mementos, which happened also to be completely genuine, into kiosks and newsstands.

By 1973, however, Shore was tiring of pranks and point-and-shoot photography. Maturity and a desire to make bigger prints than 35 mm allowed led him to pick up a Crown Graphic 4 × 5 camera and, later, an 8 × 10. The knotty problem of translating three dimensions into two on the ground glass, and of seeing how color affects every value and corner of the rectangle, forced him to slow down. He became intrigued by how “the psychological tenor of a picture is partially communicated through structural means—that the structure was not just a way of beautifying something that was there, it was integral to the whole physical aspect of the experience of seeing the picture.” His trips around the country in the mid- to late ’70s became less chaotic, more deliberate. He had learned how to drive, and his car, instead of being full of guys, often had in the passenger seat his companion (and, later, wife), Ginger Cramer. As Campany notes, by choosing large-format cameras Shore was no longer photographing “things,” as in “American Surfaces,” but “scenes.” In 1982 Aperture published forty-nine of them as Uncommon Places, his first monograph. This book (later expanded in 2004) is Shore’s masterpiece, according to those who prefer to claim him as a documentary photographer. That so many younger artists, from Yale to Düsseldorf, decided in the 1990s to work in large-format color can be attributed in no small part to him and these hypnotic pictures.

Having taught at Bard College for three decades, Shore has learned how to speak analytically about his process and general issues in photography. He has a sympathetic and responsive listener in Campany. (Shore has given many interviews over the years, but none better than this one.) Topics range from the technical—how to factor in pupil dilation while estimating an exposure in Southwest light—to the biographical. Shore was connected via Warhol, MoMA, and his own youthful eminence to an astonishing range of art personalities in the ’70s. He was friends with Ruscha, Douglas Huebler, Christo, Dennis Oppenheim, and Richard Long as well as Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander. Among the faces in “American Surfaces” are portraits of Henry Geldzahler, Douglas Ireland, Lawrence Weiner, and William Eggleston (scotch glass and cigarette in hand). Shore did a bicentennial mural project for Robert Venturi at the Smithsonian and went to lunch in New York with Paul Strand, who warned him that “higher emotions could not be communicated in color.” Since his teenage years, Shore had regularly shown new work to John Szarkowski, MoMA’s esteemed director of photography from 1962 to 1990. Critiques could be brutally short. Once, after the twenty-year-old entered the museum offices with a group of prints he was especially proud of, Szarkowski looked at them, puffed on his pipe, and said, “These are boring, hmmm?” Shore revered him nonetheless, and has called him “my teacher.”

This monograph could have used—as could Shore scholarship in general—an essay examining Shore’s relationship to Eggleston, Joel Meyerowitz, and William Christenberry and the interactions of these American pioneers of color with their curatorial mediators, Szarkowski and Walter Hopps. But this deficiency, as well as the absence of Shore’s work from Warhol’s Factory, is balanced by a generous selection of images from “Uncommon Places.” More than a dozen of these have become classics, reproduced frequently in histories of contemporary art to illustrate the ’70s revival of large-format photography. Even though more than forty years old now, they were so carefully observed and loaded with offhand detail that they have yet to petrify into clichés.

A favorite of mine was taken on June 20, 1974. It’s of a street intersection in Easton, Pennsylvania, empty of traffic except for a red-and-white VW bus parked in front of a four-story apartment house. The landlord seems to have invested in a set of green awnings to spruce up the place and attract possible tenants. In the hazy distance, across the Delaware River, are grander homes. Closer, and in sharper focus, is a red NO PARKING sign. Delicate strands of telephone wire crisscross in the air. A mood of stifling silence permeates the humid summer scene. No one is about. Only after careful study is it apparent that a child sits in a lower window of the apartment house, with nothing better to look out at than what no doubt was an unusual sight: a man covered by a dark cloth with a strange device on a tripod. Like the first page of a short story, one the photographer didn’t have to invent, it’s also a glimpse of a Mid-Atlantic river-city neighborhood in the ’70s, when the Rust Belt economy was heading south. In another ten years, the cracks in the sidewalk likely widened as town budgets began to crack as well.

Color is handled so confidently by Shore that it’s easy to forget the effort it took for art photographers before the 1970s to see in anything but black-and-white. Some of his mid-’60s New York street pictures in monochrome use high expressionist angles to create action and fragment the body in the style of Lisette Model. When he returned to the streets (2000–2002) with an 8 × 10 camera, he chose black-and-white to be contrary, because, as he says in the interview, “nobody was working” that way anymore. His most successful pictures in this mode, though, may be his upstate New York landscapes, where the ridges in tree trunks and dents in boulders are rendered in handsome silvery grays and seen close-up with his 8 × 10, as if he were making formal portraits of High Society dowagers.

Shore has never lost sight of what Conceptual techniques could do for his photographs. By design, his iBooks (2003–2008) were shot in one day with a compact digital camera. Some were image sequences with text, others performances (he would walk ten meters and take a picture). His career may have more in common with those of restless experimentalists such as Thomas Ruff than with any of his American contemporaries’. By not swearing allegiance to one way of making or presenting his photographs, Shore has been a role model for those who want to abolish the idea of exclusionary schools and credos. With its punk, nose-thumbing attitude toward the medium, “American Surfaces” is as much rude documentary as theoretical manifesto. The allover style of “Uncommon Places,” in which no area of the picture is the center of interest or meaning, may be the more deadpan and brainy.

The first photograph in this catalogue, from 1973, is like a Magritte: Against a landscape of the American West stands a billboard of a painted landscape of the American West that blocks the vista. It’s a Conceptual joke, about pictures embedded within pictures, as well as a social satire of the commercialization of the wilderness. The second photograph, also from 1973, is another familiar view in the West: breakfast at a roadside restaurant. Every item on the Formica table—pancakes with butter, half a cantaloupe, a glass of milk, a syrup dispenser, utensils, a heavy plate ringed with ersatz Indian symbols, a paper place mat with printed drawings of cowboys and prospectors—represents an American way of life and dining. “Things” in each image are identical with “scenes.”

Incongruous and contingent pieces of the world seem to become inevitable and permanent when Shore is standing in the right place in the right light. But that may be because Shore’s photographs, like the ones in the book by Walker Evans that the precocious ten-year-old studied in his New York bedroom, often act older than they are, as if we’ve known them all our lives.

Richard B. Woodward is an arts critic in New York City.