Sociologist Peter Berger is right to see academe, alongside law and media, as one stronghold of “Euro-secularity” in a sea of American faith. Not so long ago, theology was academe’s queen. Today, God talk is largely verboten in American universities, even inside religious-studies departments like my own.

Yet hard-core believers still exert a powerful hold over the imaginations of many of us charged with making sense of American religious history. For some, born-agains provoke fears of political campaigns amped up into moral crusades. For others, the God-besotted trigger nostalgia for a way of being in the world once known to parents or grandparents but now lost.

In recent years, many American scholars of religion have shifted their gaze away from the thoughts of dead white Protestants toward the “lived religion” of Catholics at prayer and Buddhists in the lotus position. But the allure of the sterner stuff of our Puritan heritage—sinners felled by spitfire preachers and theologies that crash into our ordinary lives and demand radical change—remains. A lively strain of religious history is now devoted to modern evangelicals, those heirs to the Puritans who continue to defy the Euro-secularity of academe with magical scriptures, tear-drenched altar calls, and florid prophecies of the coming apocalypse.

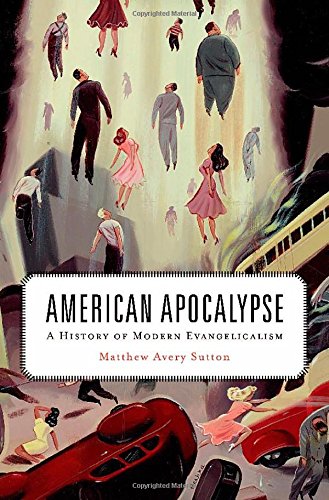

Matthew Avery Sutton’s American Apocalypse is a book about American evangelicalism from the late-nineteenth century to the present, but the term evangelical is a moving target, and Sutton (who has written previously on the Pentecostal Aimee Semple McPherson and the fundamentalist Jerry Falwell) does a good job resisting the temptation to extract from it one unchanging essence. By the early decades of the nineteenth century, just about every American Protestant was an evangelical who believed that the Bible was true, that Jesus died on the Cross for our sins, that sinners had to be converted, and that the Gospel needed to be preached.

This all began to change during the mid-nineteenth century. As Sutton explains, evangelicalism began to split under pressure from new intellectual movements (Bible criticism, comparative religion, evolution) and social shifts (immigration, industrialization, urbanization). He calls the two chief camps liberal evangelicals and radical evangelicals. After the publication of a series of tracts called The Fundamentals (1910–14), and especially during World War I, a large subset of radical evangelicals started to refer to themselves as fundamentalists. This was when the American Protestant scene took on something like its current shape, with liberal Protestants on the left, evangelicals on the center-right, and fundamentalists on the far right.

In highlighting this continuity, Sutton is following the lead of a new, revisionist view of the evangelical movement. For decades, scholars have told and retold a story about a “Great Reversal” in American evangelicalism—a chronicle that puts the Scopes “Monkey Trial” of 1925 front and center. Before this widely publicized showdown over the teaching of evolution in Tennessee’s public schools, evangelicals were politically active progressives. In fact, they spearheaded many of the great social-reform movements of the nineteenth century (abolitionism included). The fundamentalist standard-bearer at the Scopes trial was William Jennings Bryan—a Democratic populist who brought the evangelical-reform tradition into the forefront of liberal politics. Bryan won at trial but lost in the court of public opinion, and from that moment on fundamentalism became a byword among liberal and secular elites for ignorance and backwardness. Fundamentalists responded to this embarrassment by withdrawing from public life. For decades, they worked not to reform American society but to build and nurture their own denominations, Bible institutes, publishing houses, radio stations, summer camps, and secondary schools and colleges. They reemerged after World War II to fight Communism and (even more powerfully) in the late ’70s to combat liberalism, this time in league with political conservatives and the Republican Party.

But American evangelicals hadn’t been in exile, Sutton argues: Contrary to the mythology of the Great Reversal, they “never retreated” from politics, cultural or otherwise. During the ’20s and ’30s, they protested the emergence of the “new woman,” with her bobbed hair and short skirts. In the 1928 presidential campaign, they helped to block Democrat Al Smith—a “friend of negro rapists,” according to fundamentalist pastor Ben Bogard—from becoming the first Catholic president. And they actively opposed FDR’s New Deal, which they considered a federal-government power grab.

Most of all, he stresses, the radical Protestants of the modern age embraced apocalypticism, which he sees as the beating heart of contemporary American evangelicalism. This tradition’s distinguishing features, Sutton argues, were narrative rather than doctrinal. Instead of forcefully upholding established dogmas such as the Virgin Birth or the resurrection of the body, radical evangelicals staked their identity as believers on gothic tales of Antichrist, tribulation, Rapture, and the final battle between God and evil at Armageddon.

According to the happiest reading of this end-times story—the doctrine known as “postmillennialism”—the prophesied thousand-year reign of Christ on Earth would be ushered in not by Jesus but by activist Christians, who would prepare the way for the Second Coming by repairing the world in his image. However, Sutton’s radical evangelicals were premillennialists, who believed that Jesus would return before his thousand-year reign. In the meantime, things would go from bad to worse.

This gruesome tale of imminent apocalypse would seem not only to chill political activity but to put it into a deep freeze. Why work to pass a law or kvetch about sexy dancing if the world is coming to an end in a few years? Yet according to Sutton, apocalypticism has not merely defined evangelicals and fundamentalists in modern America—it has spurred them to political action. How so? What to make of this “premillennial paradox”?

Sutton argues that apocalypticism lent a sense of urgency to Christian life. Like a ticking clock at the end of a football game, it raised the stakes and stirred the emotions. But the conviction of impending judgment depended on the ability of premillennialists to connect the dots between their readings of the Bible and current events—to find in newspaper headlines the fulfillment of biblical prophecies. That job got much, much easier, Sutton argues, when the United States and its allies went to war with Germany in World War I. The defining moment for modern American evangelicalism came not in the “warfare between science and religion” symbolized by the Scopes trial, Sutton concludes, but in the warfare that bloodied the globe between 1914 and 1918.

With American troops dispatched to foreign lands to fight the good fight for democracy, Sutton’s evangelicals could have gone gentle into the good night of the apocalypse. Instead, they chose to stand and fight in the political realm, against the prophets of secular worldly power. And when World War II came and Mussolini and Hitler began auditioning for the role of Antichrist, American apocalyptic believers waxed increasingly patriotic and became even more politically engaged. This same obsessive quest to identify an Antichrist seeking to build one global regime led them to speak out against big government and to fight the New Deal. And while premillennialist anxiety about the encroaching end-times prompted the great postwar evangelist Billy Graham to travel the world to win souls for Christ, it also led him to befriend presidents and to champion the United States as a “Christian nation.” By sheer force of charisma and prophetic certainty, Graham brought the premillennial paradox to the center of our national life.

American Apocalypse is the best history of American evangelicalism I’ve read in some time. Sutton strews his chronicle with little pleasures. He reminds us of the evangelicals who rejected the view that the United States is a Christian nation in the belief that all nation-states are fallen. He revisits the work of ostensibly “literal” interpreters of the Bible, who took the “seventy weeks” in the Book of Daniel to refer to seventy times seventy years. And he surveys the track record of antistatist fundamentalists, who denounced the civil-rights movement as an imposition of big government while calling on all the coercive powers of that same government to enforce Prohibition and outlaw abortion.

Overarching all the narrative detail is an important argument. Sutton’s central concern—to shift attention from the metaphorical warfare that took place at the Scopes trial to war itself—makes a lot of sense. If you view modern American evangelicalism (as I do) as a Protestant theological impulse in the process of becoming a Republican political program, then there is ample evidence that the same forces that drew Woodrow Wilson and FDR into war turned evangelicals into conservative political activists.

Some of Sutton’s claims can be a bit belabored. At times he relies heavily on minor figures who help his argument while discounting major ones who don’t. J. Gresham Machen, one of early-twentieth-century America’s most important antimodern theologians, rejected premillennialism. Cyrus Ingerson Scofield, the premillennialist author of the enormously influential Scofield Reference Bible (1909), insisted that the Christian Church was an utterly apolitical “spiritual kingdom.”

However, as someone who has spent years trying to understand the culture wars as a recurring theme in American history, stretching from the election of 1800 through the anti-Catholic and anti-Mormon campaigns of the nineteenth century and into Prohibition and repeal and the rise of the Religious Right—I found Sutton’s attempt to place apocalypticism at the center of his story wonderfully provocative. One of the puzzles of the culture wars, and of our current epidemic of ideological polarization, is how politics morphs from Max Weber’s art of compromise into Sun Tzu’s art of war. Many have traced this shift to the steady migration of religion into the political realm, but what made culture warriors uncompromising was the injection of a certain sort of religion. Sutton points us toward that faith’s ingredients, which include not only apocalypticism of the premillennial sort but also belief in the omnipresence of war itself—real war—which provided a blueprint for a new way of practicing politics as war. What apocalypticism lent to US politics it still lends to religion: a sense of urgency and a rhetoric of militancy—a “passion to right the world’s wrongs,” here and now, while resisting the temptation to resort to postmillennial half-measures along the way. In short, if you want to understand why compromise has become a dirty word in the GOP today and how cultural politics is splitting the nation apart, American Apocalypse is an excellent place to start.

Stephen Prothero is a professor in Boston University’s department of religion and the author of the forthcoming book How Liberals Win: The Story of America’s Culture Wars and the Lost Causes of Conservatism (HarperOne, 2015).