Most of the people who saw the 2009 film Julie & Julia agreed: It would have been better if it were simply Julia. (Indeed, one fan, who happened to be a film editor, was heralded as a hero vigilante when he posted a Julie Powell–free version of the movie called & Julia online.) Although the story of twentysomething blogger Powell—breaking down in front of her stove on a nightly basis, writing about her travails with complicated soufflés and slimy innards in her Queens apartment—should have been by far the more relatable of the two, somehow we were still less interested in her than in seeing good old Julia Child, as portrayed in all her tootling jollity by Meryl Streep, set loose in the lush landscape of 1950s France. The all-too-real present was nothing compared to the comfort of hearing the winning, familiar story of Julia’s rise to fame yet again.

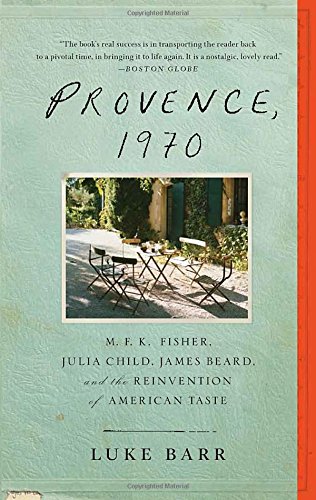

Better than even & Julia, though, would be a film version of Luke Barr’s Provence, 1970: M. F. K. Fisher, Julia Child, James Beard, and the Reinvention of American Taste (Clarkson Potter, $15). The book, which was recently released in paperback, also features Child (when it comes to Julia, we can’t stop, won’t stop) and the forenamed cast of food writers plus a few more to boot, all of whom are guaranteed to please—not a whiny Generation Xer with a bad day job among them. There is gorgeous food, impressive scenery—all those twisty little roads and green vistas!—and lots of backstabbing. Even the driver who ferried this illustrious pack around France is engaging, not least because he also chauffeured Picasso, Elizabeth Taylor, and Jack Benny. (It doesn’t hurt that his wife made a killer lemon tart and kept the recipe secret even from the great Child.)

All Julia aside, it was Barr’s great-aunt, the formidable M. F. K. Fisher—she had, he recalls, “a haughty toughness about her”—who brought about this little jewel box of a book. A few years ago, Barr discovered Fisher’s notes on the journey to France she took in the winter of 1970 and extrapolated from them a story about her, and about the moment when American cooking turned definitively (at least in Barr’s telling) away from the pomp of the classic “Grand Palace” French style. The food this little band of Americans abroad began making (and teaching others how to make) was based on the traditional idea that fidelity to flavors and methods, rather than fussiness and show, was the foundation of any good cuisine. They were ready to throw off pretension, whether the dish being made was a gratin dauphinois or a New England clam chowder. As Barr says, entering Fisher’s mind as he’s wont to do here and there, “Having long ago escaped America in order to discover France, she was now wondering if she needed to escape France to find herself.”

Indeed, Fisher had returned to her former stomping grounds on a kind of memory tour, going so far as to sail over on an ocean liner rather than fly. Her books about her life and culinary awakening in France as a young woman in the ’30s and ’40s had made her name years before, and she was set on putting that phase into perspective and discovering what the next one would be. As she wrote in her journal: “I am in southern France, and it is December, 1970 and I am 62 1/2 years old, white, female, and apparently determined to erect new altars to old gods, no matter how unimportant all of us may be.”

Coinciding with her trip were Provençal visits by Child and her husband, Paul, who were spending Christmas at La Pitchoune, their house in Plascassier, which was built on property belonging to Simone Beck, a coauthor of the Mastering tomes (whom Child referred to in private as “la Super-Francaise”); James Beard, who rather improbably had arrived in the land of bread, cheese, pâté, and wine to check himself into a diet clinic to improve his failing health; and Judith Jones, the redoubtable editor who had brought Mastering the Art of French Cooking into being, and her husband, Evan. The eccentric, tightly wound Richard Olney, who had moved to France several decades earlier and lived in artistic semi-seclusion nearby, had just published The French Menu Cookbook in the US to great acclaim; he plays the villain in Barr’s story. Olney appeared at every meal over these few weeks, including an elaborate one he hosted himself, with a baguette-size chip on his shoulder. About his first meeting with Beard, who was many years his senior and had been nothing but generous to him, he snarked that Beard “had arrived at the oracular period in his career, when he expected listeners to bow in silence to his superior wisdom. I bowed in silence to nonsense as long as it did not touch me, personally.” In conversation with the now sorely under-appreciated writer Sybille Bedford, who lived nearby and shared his viciousness—she zips through these pages like a gossipy poison dart—he went even further: “I have a feeling,” he told her, “that I shall shortly break ties with the whole fucking business and run and hide (who knows, perhaps paint). I’m more and more surprised, in retrospect, that anyone accepted to publish my book.”

Nevertheless, when it was his turn, he cooked up a feast for his colleagues, one of the many meals Barr lovingly details (right down to including the menus). The artichokes were straight from the garden and cooked with saltwater and thyme, which preserved their flavor if not their color—the traditional method bleached them white for appearances. He made an elaborate daube à la Provençale, as well as a roulade of sole filets with sea-urchin mousse that had to be laboriously pushed through a sieve, and he finished the work long before his guests arrived so he could appear at the table in all his bohemian ease. There was much fetishistic talk about wine and pairings (and a less-successful sorrel mousse). Olney delighted in the elitism, but Fisher, much as she enjoyed the food, was as impatient with this mode of discourse as Olney was with what he considered her“silly, pretentious, sentimental and unreadable drivel.” Barr writes, “It was all too precious for her taste. There was a time when she might have reveled in such conversation. But no longer.”

After several weeks of these encounters, during which tensions between various factions (Child v. Beck; Fisher v. Bedford; Olney v. the World) rose and fell, Fisher decamped first for Arles, then Avignon, and finally Marseille, where she settled into a much-loved hotel for a solitary Christmas and some self-reckoning. “Always before, in France, I have fought a hard battle within, to return to America happily. I have wanted to stay here. But by now I have decided to end my life in California, as far as one can decide such things,” she told herself on that frigid Christmas Eve.

[[img]]

Her decision was made easier by the fact that American cuisine had already begun to change, in no small part due to the work of the people she’d spent the past few weeks with. Alice Waters and Jeremiah Tower would soon open Chez Panisse in Berkeley, inspired by the seasonal, fresh approach of Olney’s French Menu Cookbook and its follow-up, Simple French Food, which one reviewer noted “really teaches you to cook French in a way I’ve never seen before . . . you acquire the methods, the tour de main . . . that are the heart and essence of French food.” Child moved on from complicated French dishes to food that was simply From Julia Child’s Kitchen. Beard published Beard on Bread, a classic to this day, and Williams-Sonoma began its ascent.

All of these stories are amply documented by now, but what Barr’s book lacks in new information (with the exception of Fisher’s journal) it more than makes up for with elegant writing and the author’s boundless affection for his players; even Olney is somewhat rehabilitated by the end of the tale. Barr proves himself to be a deserving heir to his great-aunt’s legacy, though there’s an irony in his having added yet another book to the canon of literature that idealizes this period of food history, even as he recognizes that one of the great themes of Fisher’s writing is “the nostalgic past as viewed from the unsentimental present.” The idea that her own great-nephew would someday write a book about her life, longing to recapture the feeling of that 1970 winter (at the end of the book, Barr rents La Pitchoune and takes his family there for an extended vacation), would not necessarily have pleased her; she was too practiced in and committed to moving on—no matter what. Our present, of course, is nothing if not sentimental about the days when one’s first meal in France opened the gateway to a whole new world. As nice as it is to have good bread in America, and to experience, more generally, the kind of eating that Fisher and Waters, among others, ushered in, it has made the world just a little bit smaller, too, and thus our adventures in it a little less novel. Barr’s nostalgia for the moment in his great-aunt’s life when she chose to leave her own nostalgia behind reminds us that one woman’s future inevitably becomes someone else’s cherished past. It seems unlikely we’ll ever stop wanting to read books about Fisher, Child, et al. Some old gods are worth those altars.

Melanie Rehak is the author of Eating for Beginners (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010).