The St. Louis County grand jury’s decision not to return an indictment of police officer Darren Wilson in the shooting death of Michael Brown was at once appalling and entirely predictable. Grand juries usually defer to the will of the prosecutors who marshal the cases on their dockets, and Bob McCulloch, the district attorney in the Brown case, has a long track record of siding with the police over his twenty-five-year career. This, too, can hardly come as a shock, given his strong ties to the law-enforcement community: McCulloch’s father, brother, and cousin were all St. Louis police officers, and his father was killed in an incident involving a black suspect.

But while the formal legal system remains largely indifferent to such reflexive displays of white privilege and pro-cop bias, white America’s popular consensus on race and crime relies on an uglier bit of folk mythology. When racist commentators are confronted with a case such as Brown’s—or the deadly chokehold assault on Eric Garner in New York, which also failed to yield a grand-jury indictment—they try to shift the debate to new ground entirely, citing the alleged epidemic of black-on-black crime. Here, for example, is how former New York City mayor Rudolph Giuliani grandstanded before the cameras on Fox & Friends on the day of the St. Louis grand jury’s announcement: “The danger to a black child in America is not a white police officer,” he declared on an all-white panel. “That’s going to happen less than 1 percent of the time. The danger to a black child—if it was my child—the danger is another black.” He then went on to advance the absurd claim that “there is virtually no homicide in the white community.”

Likewise, after George Zimmerman was acquitted of all charges in the killing of Trayvon Martin in 2013, a factoid distributed widely on conservative social media claimed that “in the 513 days between Trayvon dying, and today’s verdict, 11,106 African-Americans have been murdered by other African-Americans.” The fact-checking website PolitiFact discovered that that tidbit was “mostly false,” the apparent result of some shoddy calculations using crime statistics that were almost a decade old. But for many Americans, the point stood: Whites provoked by racial bias to kill black people constitute a nonissue when compared to the real problem of blacks killing other blacks.

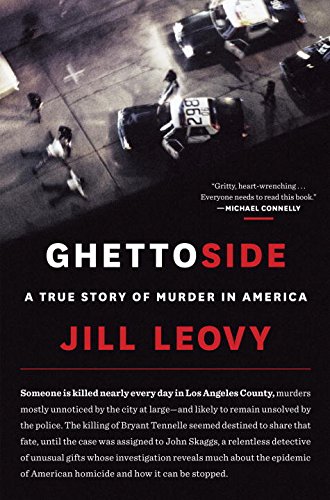

This is the misguided racial zeitgeist into which veteran journalist Jill Leovy releases her powerful first book, Ghettoside, an in-depth account of a South Los Angeles murder and the subsequent investigation. Though she focuses on a single homicide in a small swath of LA, Leovy uses her narrative to examine a host of larger questions about police conduct, violence, and racism in America. The result is a true-crime book that leaves the reader haunted not by its cast of criminals but by the society in which those criminals operate.

Leovy is perhaps best known for starting the Los Angeles Times’s Homicide Report in 2007. Struck by the disparity in how the media covered murder—with high-profile and salacious homicides treated more prominently than the everyday violence that occurs in the less-rich-and-famous communities of Southern California—Leovy launched a blog to give equal coverage of every murder in metro LA. The project, she reasoned, would bear witness to the idea that no life is worth less than any other.

In a 2010 NPR interview, Leovy expressed frustration with America’s obsession with finding justice for murdered white women while ignoring the far greater numbers of black men dying from gun violence in cities across the country.

“The truth about homicide is that it is black men in their twenties, in their thirties, in their forties,” she said. “The way we guide money and policy in this country, we do not care about those people. It’s not described as what’s central to our homicide problem, and I wanted people to see that” in the Homicide Report.

Leovy writes early in Ghettoside of an acronym taken from the “unwritten code of the Los Angeles Police Department”: NHI—No Human Involved. It’s what some cops would say after they happened on the bodies of black men killed by other black men. “It was only the newest shorthand for the idea that murders of blacks somehow didn’t count,” she writes:

“Nigger’s life cheap now,” a white Tennessean offered during Reconstruction, when asked to explain why black-on-black killing drew so little notice.

A congressional witness a few years later reported that black men in Louisiana were killed and “a simple mention is made of it, perhaps orally or in print, and nothing is done. There is no investigation made.” A late nineteenth-century Louisiana newspaper editorial said, “If negroes continue to slaughter each other, we will have to conclude that Providence has chosen to exterminate them in this way.” . . . An Alabama sheriff of the era was more concise: “One less nigger,” he said.

In short, for more than a century now, America has turned a blind eye to murder in black communities, suggesting that many in the white mainstream regard the so-called black-on-black-crime problem as something of a solution. (Indeed, Leovy caught one LAPD officer calling a successfully prosecuted gang killing “two for the price of one,” as one man was going to jail and the other was dead.) African Americans caught possessing marijuana are prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law, but justice for murdered black people takes a backseat in most urban law-enforcement operations. The media won’t cover homicides in black communities—Leovy tells of parents literally begging journalists to write about their dead sons—and many cops approach these cases sluggishly, if at all. “In Jim Crow Mississippi,” Leovy writes, “killers of black people were convicted at a rate that was only a little lower than the rate that prevailed a half century later in L.A.—30 percent then versus about 36 percent in Los Angeles County in the early 1990s.”

At the center of Ghettoside, which takes its title from the term a Watts gang member used to describe his neighborhood, is the 2007 killing of eighteen-year-old Bryant Tennelle. Another young black man gunned Tennelle down as he was walking near his home in South Central—not an uncommon occurrence for the time and place. What was uncommon was that Tennelle’s father, Wally, was a well-respected homicide detective in the LAPD. Also uncommon was the detective assigned to the case, a determined bulldog of a man named John Skaggs.

White, Republican, and middle-age, Skaggs fit the stereotype of a cop who might have written off the shooting as an NHI case. But Skaggs was different. The son of a former homicide detective, he threw himself into his work in a way rare among his peers, animated as he was by the belief that every murdered person—black or white, gang member or not—deserved a good detective working on his or her behalf. He knocked on suspects’ doors and took jittery witnesses out for meals—the little things that can produce major investigative breakthroughs over time. These were precisely the routine steps his colleagues failed to take in order to wind up homicide investigations in many African American neighborhoods. Skaggs’s tenacity paid off, and while some LAPD detectives were solving less than half their cases, he tried to keep his clearance rate at 80 percent or higher. He dismissed detectives who couldn’t keep up as “40 percenters.”

No spoiler alert should be required here before noting that Skaggs and his dogged team of partners and subordinates solve the case. It turns out that Tennelle’s killers mistook him for a rival gang member, even though he had no gang affiliations at all—he was simply wearing the wrong hat as the wrong group of people drove by. It’s a tragedy, but the grander tragedy that impels Ghettoside—and the reason it shouldn’t be overlooked or treated as just another true-crime chronicle—is, as Leovy writes, that “where the criminal justice system fails to respond vigorously to violent injury and death, homicide becomes endemic.” As a result of this malign neglect, she argues,

black America has not benefited from what Max Weber called a state monopoly on violence—the government’s exclusive right to exercise legitimate force. A monopoly provides citizens with legal autonomy, the liberating knowledge that the government will pursue anyone who violates their personal safety. But slavery, Jim Crow, and conditions across much of black America for generations after worked against the formation of such a monopoly. Since personal violence inevitably flares where the state’s monopoly is absent, this situation results in the deaths of thousands of Americans each year.

In other words, America’s black-on-black-crime problem isn’t going to be solved by black boys pulling up their pants or refraining from using the N-word or any of the other condescending solutions cable-news pundits have eagerly urged on the monolithic “black community” of their feverish imaginings. Our justice system can prevent blacks from killing blacks in the same way that it prevents whites from killing whites: by investing time, money, and police resources into proving that black people are valuable to our society—by extending them material and cultural support while aggressively investigating and prosecuting the perpetrators of their violent deaths. Unfortunately, such a commitment is expensive and arduous, and it requires white Americans to admit that, in some ways, black-on-black crime is an outgrowth of historic white-on-black crime. It’s much easier to watch TV’s one hundredth Natalee Holloway special and tolerate cops who write off black murder victims as subhuman.

Years ago, I worked as a communications coordinator at a small nonprofit in Los Angeles. Our program taught theater skills to the same kinds of kids depicted in Ghettoside, who would complete their studies by writing, designing, and starring in their own short plays. I never worked directly with the children, and so it wasn’t until the end of the second play showcase in my first year on the job that I saw how many of the performances ended with an angel or some other mystical figure coming to save everyone from lives devastated by drugs, gang violence, and poverty. Every now and then, a police officer or teacher would materialize onstage to deliver the climactic moment of salvation. But most of the time it would be a miracle.

Cord Jefferson is a writer living in Los Angeles.