It’s counterintuitive to think of the British Museum as a happening spot, but for a long time its reading room served as a premier gathering place for London’s brainy bohemians. In the 1880s, these included radicals like George Bernard Shaw, Henry Havelock Ellis, and Eleanor Marx, Karl Marx’s youngest daughter. They worked there, and they talked during smoke breaks and visits to Bloomsbury tea shops. They moved fluidly between politics and the arts, deploring factory conditions as fervently as they dissected Ibsen’s plays. The reading room was a vital seedbed for such Victorian-era social-reform causes as women’s rights and trade-union organizing.

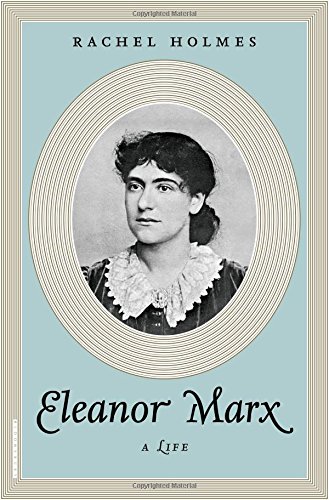

It was also a pickup scene. Edward Aveling, a science lecturer, playwright, and political activist—and a notorious flirt—described the reading room as “in equal degrees a menagerie and a lunatic asylum” and made a tongue-in-cheek proposal that it be segregated by sex so as to bring about “less talking and fewer marriages.” Among the liaisons fostered there was Aveling’s with Eleanor, an energetic feminist and socialist who, after her father’s death in 1883, blazed a bright trail of her own. As Rachel Holmes illustrates in her engaging new biography, she emerged as one of the London intellectual Left’s leading thinkers and activists, forcefully insisting that advances for women and advances for workers be fought for in tandem.

And yet even as she strode confidently across the public stage, Eleanor attached herself, for fourteen years, to Aveling, who turned out to be the sort of person we might now call a lying scumbag. This mystified her friends, and it remains something of an enigma today: While she and Aveling were never legally married, she considered herself his wife, and she stood by her disastrous man until the very bitter end.

Then again, a little Marx-family history reminds us what strange arrangements and dark secrets lay behind the scrim of Victorian domesticity. One need look no further than Eleanor’s own parents, a prototypically unpredictable Victorian union: Jenny von Westphalen, a debutante from an aristocratic Prussian family, and Karl Marx, a family friend of hers but also a Jewish philosophy student. This match, like many others forged in the centers of European intellectual life, suggests that the more privileged partner aspired to something other than her foreordained social destiny—in Westphalen’s case, the life of a typical bourgeois woman in the provincial German city of Trier.

She went on to endure many hardships, none of them bourgeois. Three of the six children she bore died young; her family, which eventually settled in London, was in near-constant financial straits; and in 1851 her housekeeper and confidante, Helene “Lenchen” Demuth, gave birth to a son fathered by Karl. (After that, Lenchen stayed on with the Marxes, while the child, Freddy, was sent to live with another family. For most of her life, Eleanor understood Freddy Demuth to be the unacknowledged son of Friedrich Engels.)

As Holmes tells it, young Eleanor—nicknamed “Tussy”—was protected from the brunt of all that. With two mother figures in Jenny and Lenchen, as well as two much older sisters, she was the pet of the household, who by the age of six could recite large chunks of Shakespeare and, a few years later, wrote letters to Abraham Lincoln advising him on the Civil War. Her father doted on her, told her stories, gave her books, and played chess with her—when he wasn’t at work on Das Kapital, or felled by illness, or shuffling debts. Periodically, the Marxes’ financial situation grew dire, but then a loan from a family member or a gift from the well-off, avuncular Engels would make it possible for Karl to continue his low-paying work.

Eleanor identified with her father, and he with her (“Tussy is me,” she recalled him saying). She received almost no formal education but learned at his feet, and in her early teens she became his research assistant and secretary—much more than an honorific post, as local and national workers’ organizations throughout Europe began expanding and consolidating across borders. Karl was at the forefront of the new international movement, and the revolutionary leaders of Europe became Eleanor’s pen pals. Her first long romantic relationship was with Hippolyte Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, an exiled Parisian Communard seventeen years her senior.

By then she was surely aware of her mother’s depressions and of some of the tribulations that marriage and childbearing had brought to her two older sisters. Laura, the middle Marx daughter, would lose all three of her babies at young ages, while the eldest sister, nicknamed Jennychen, would find herself unhappily married and exhausted by caring for her six children. Like her mother before her, Eleanor wanted to make a different sort of life for herself.

Holmes, the author of two previous biographies and a coeditor of an anthology called Fifty Shades of Feminism, writes with great sympathy for her subject. Her purpose, it seems, is less to analyze or contextualize Eleanor Marx than to tell us the story of an exemplary public figure. To the extent that Holmes gets under Eleanor’s skin, she characterizes her as a woman with too much empathy for others, a condition that left her unable to care for herself and predisposed toward “the whole infuriating syndrome of Victorian feminine neurosis”—aka hysteria.

The vivacious girl became a bold woman who tended to overtax herself. In her twenties, she undertook paid editorial work, translated her lover’s memoir of the Paris Commune, continued to help her father, and tried to become an actress. Karl grudgingly agreed to pay for stage training, but before beginning her lessons, during a period when her father, her cancer-stricken mother, and Lenchen traveled to France—leaving Eleanor to her own devices for six weeks—she worked herself to the bone, barely ate or slept, and suffered a nervous collapse. Holmes tallies the causes:

Use of too many stimulants. Insomnia. Depression. Frustrated desire. Surfeit of unchannelled ambition, intellectual talent and energy. Resentment at being for so long a repressed, obedient daughter fighting her contrapuntal desire to break free and strike out on a line of her own. Passionate will to live her own life. Underpinning the intensity of her reaction: guilt, regret, foreboding, self-doubt, insecurity. And . . . her awareness . . . that she was losing her mother. Grief.

No doubt at least some of these were to blame, but in leaping from the onset of Eleanor’s crisis to what reads like voice-over narration for a TV documentary, Holmes seems more interested in Eleanor the feminist case study than Eleanor the woman. It seems worth noting that the meltdown happened after she had been freed from her daughterly obligations and left alone to work. The room of her own quickly became a prison.

It’s also striking just how much loss Eleanor had to contend with during her young adulthood. The story of the Marxes is laden with physical and mental illnesses. To be sure, disease and mortality rates were high in Victorian London as a whole, but the litany of Marx-family travails gives a sense of the emotional toll behind the statistics. In 1881, just before Eleanor turned twenty-seven, Jennychen died; both her parents died within the next fifteen months. As a result, Holmes suggests, Eleanor was released from her filial obligations: “Now that her father was dead, the ceiling was lifted from Tussy’s sky.” Yet what a dark sky that must have been. A little more than a year after Karl’s death, she moved in with Aveling.

Eleanor the writer and political agitator came into her own during the years that followed. Her prodigious activity ranged from labor organizing and speechmaking to completing the first English translation of Madame Bovary. She and Aveling played active roles in Britain’s new socialist organizations. She stood with the dockworkers, the gasworkers, the women onion-skinners working “twelve to fourteen hour shifts with their arms plunged elbow deep into noxious chemicals.” She fought for expanded suffrage, the eight-hour workday, universal education, and women’s emancipation. And she and her fellow socialists pictured a

not-too-distant future in which we would all put in our few hours of work and then devote the rest of the day to artistic pursuits or family life.

It’s enough to make you wonder, not for the first time, why it is that some generations look at society and see it as up for grabs, open to reinvention, while others, like our own, seem so much more constrained, even fatalistic. But I also wonder whether one source of Eleanor’s trouble, or even of the trouble with being a Marx, lay in that combustible mix of historical-materialist analysis of the present and dreamy visions of what might be possible in the future. In an 1886 essay, “The Woman Question: From a Socialist Point of View,” which Marx cowrote with Aveling, the authors are hardnosed critics when it comes to the predicament of women—they refer to weddings as “business transactions” that lead to the “perennial labour and sorrow” of childbearing. And then they float off into the wishful ether, envisioning a time when marriages will be an ideal “blending of two human lives,” as they put it. “Husband and wife will be able to do that which but few can do now—look clear through one another’s eyes into one another’s heart.”

What makes the saga Holmes relates especially poignant is that even as Eleanor and Aveling were at work on this essay, their own relationship was already a mess. He was a dogged philanderer, who would leave Eleanor at home while he “dine[d] out” and spent money she earned on his mistresses. “The solitude is almost more than I can bear,” she wrote to a friend, alluding to “the almost constant effort not to break down.” Her own partnership testified to a truth overlooked in the essay: namely, that in love and marriage, not all power can be reduced to economics. Trained in childhood to tolerate her father’s erratic earnings, periodic absences, and bouts of liver trouble, Eleanor now put up with Aveling, who had a habit of falling ill in the wake of his sexual infidelities and wanton expenditures, retreating behind “sudden, dramatic afflictions to throw her off the scent,” as Holmes writes. After a string of betrayals, she learned in 1898 that Aveling had married a young actress. Shortly after this crippling revelation, she took poison and died.

It’s the public Eleanor Marx whom Holmes wants us to remember. In the afterword, she reminds us that Eleanor and her confederates fought for and won greater measures of justice and freedom, gains we are in danger of losing in our own era of triumphal capitalism. But the personal trials of Eleanor Marx leave at least as strong an impression, and they too speak to unresolved questions of our own time. The more beholden we become to the “logic” of the market, the more we will struggle, as Eleanor did, to balance profitable work with the devalued work of caretaking. And the idea, which she fought for both publicly and privately, that we might all have a higher degree of control over our own time, that technology would actually free us from obligations rather than suck up more hours—whatever became of that?

Incidentally, the reading room at the British Museum has closed. Its library holdings were transferred elsewhere in 1997, and the reading room was retooled as a reference center, then served as a temporary exhibition space until 2013. Now, according to its website, the museum is “consulting widely” to determine a use for it.

Karen Olsson’s second novel, All the Houses, will be published in the fall.