The piney backwoods of East Texas might be the unlikeliest place on earth to produce a writer like William Goyen. Cultured and restless, he escaped via the navy, and he might have easily become an artist who left home and never looked back. Instead, that “pastoral, river-haunted, tree-shaded, mysterious and bewitched” landscape loomed large, no matter how far he traveled. “Standing before great paintings in Venice or Paris, I saw my own people in Rembrandt’s, my own countryside in Corot’s, Europa was my fat cousin in Trinity Texas.” The son of a lumberman, Goyen, born in Trinity in 1915, spent his childhood shadowed by the Ku Klux Klan and tent preachers, but also enlivened by the rough poetry of Texas speech. He was a student of music and art, a bisexual, a theater person—it’s not surprising that he felt he couldn’t live in the place he’d grown up. But he couldn’t abandon it, either: “I accepted it as a kind of destiny and often as a curse.” This dual state of exile and homesickness became a defining characteristic of his work: Starting with his debut, The House of Breath (1950), nearly all of his astonishing, lyrical novels and stories reveal a love for that lost landscape and seek a reckoning with the people he knew there.

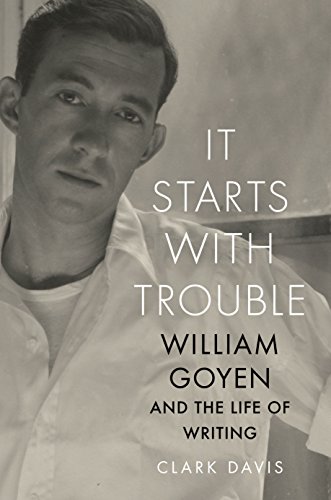

Clark Davis’s biography It Starts with Trouble, the first complete account of Goyen’s life, suggests that the entirety of the novelist’s work might be seen as “experimental spiritual autobiography.” This approach makes sense: A highly inventive writer of musical prose and intensity, Goyen “sought what he called the ‘living voice,’ the immediate, at times desperate, presence of an emotionally charged self.” In his novel Arcadio (1983), one of the most moving and thoughtful expressions of human loneliness I have ever read, a hermaphrodite travels in a circus as an object of lust and curiosity. Though stuck in the confines of a carnival world, Arcadio also reaches out to the reader: “there in the dark I have sung you my very own life.” In Goyen’s short stories, too, an urgent act of storytelling often frames the work. As Davis puts it, a story for Goyen was never “merely a story,” but “a demand for an unfiltered intimacy with a potential ‘beloved.’”

This passion also makes for a rich life, as told by Davis in anecdotes about Goyen’s parents, his friendship with the theater director Margo Jones, his love relationship with the painter Joseph Glasco, and his marriage to the actress Doris Roberts. The archival evidence is just as compelling. “You just would not hold back that wild night,” Goyen wrote to Jones, “naked and crazy in the Stoneleigh Hotel in Dallas, raging with hurt and failure and disappointment and booze and pills, with the Ravel playing and the Stravinsky.” There’s also a harrowing letter from Goyen’s mother: “If that is the kind of literature you are going to write, I hope you never succeed (and you won’t). I have all ways [sic] felt like you will write the highest and most cultured things and the good of the world, and be a help to mankind, instead of the nasty, vile, and sinful part.”

Goyen’s career had a serendipitous if delayed beginning, after his years on a battleship during World War II and an anguished parting with Texas (“If you leave, I’ll die,” his mother said. “If I don’t leave, I’ll die,” Goyen replied). Through chance, Goyen landed in El Prado, New Mexico, where he found a job waiting tables. One evening, Tennessee Williams, Mabel Dodge, and Frieda Lawrence, the widow of D. H. Lawrence, dined at the restaurant where he was working. When the restaurant owner told them about Goyen’s writerly aspirations, Lawrence invited Goyen to tea. During their long, close friendship, she introduced Goyen to the British poet Stephen Spender and others who helped his literary career.

“All serious art celebrates mystery, perhaps,” wrote Joyce Carol Oates, “but Goyen’s comes close to embodying it.” Reading Goyen is to be immersed in an opera of language (arias inflected with Texas idiom), one uncannily addressed to you in particular. There’s also “a deliberate assertion of the handmade” in his work and a naked expression of emotion, which might be the most radical element of all. Not everyone knew what to make of The House of Breath, a novel drenched in the erotic, with voices lent to rivers and cistern wheels, its structure more like song than story. But it was widely praised (Katherine Anne Porter said it contained “long passages of the best writing, the fullest and richest and most expressive”), and it launched Goyen’s career.

He went on to write four more novels, four story collections, two works of nonfiction, a collection of poetry, and five plays. And yet, despite the awards and accolades, and the success of some of his novels in Europe, most of Goyen’s books went out into the world underpromoted or misunderstood.

Struggle ran through Goyen’s fiction and his life. He worked as an editor in the early 1970s. The job brought him some success, but the time away from writing took its toll and fueled his alcoholism; he was eventually fired. He sometimes cloaked his homoerotic desires and sometimes didn’t, but the erotic is never far from the surface. “For me, literature documents lust,” Goyen wrote in his journal. Even in his darkest moments, writing retained the power of salvation. Goyen said in an interview, “Style is, or has been, for me, the spiritual experience of my material,” and his stories invoke angels, visions, and gospels. These two realms of the erotic and the spiritual, “ghost and flesh,” form the knot that can never quite be unraveled at the center of Goyen’s storytelling.

Toward the end of his life, Goyen quit drinking and wrote in a letter, “to Hell with editors and publishers and reviewers and critics and booksellers.” Despite the redemptive power he found in making “stories only for my self,” he said what started him writing was “trouble,” not “peace.” Just before he died, in 1983, Goyen perfected the spirit-flesh tensions in his work with the emblematic figure of Arcadio. A hermaphrodite with a worldview informed equally by the Bible and the whorehouse, Arcadio might be Goyen’s greatest achievement and his most realized character—one who gave voice, like Goyen, to both the sacred and the profane.

René Steinke is the author of Friendswood (Riverhead, 2014).