I always tell people that my favorite book is Reckless Disregard. That is Renata Adler’s account, published in 1986, of two high-profile libel trials that took place in New York City in the early ’80s. Those are Westmoreland v. CBS et al. and Sharon v. Time.

The Sharon was Ariel Sharon; Westmoreland was the US Army chief of staff; and that et al. included Mike Wallace. Superstar lawyers Floyd Abrams and David Boies swan through Adler’s chronicle. Reckless Disregard originally appeared as two pieces in the New Yorker, if you can imagine such a thing, and so the book gets to end with Cravath, lawyers for CBS, threatening to sue the New Yorker and Knopf for . . . well, nothing really. “The CBS-Cravath harassment did not lead to (or require) a single change in the manuscript,” Adler gets to write.

This is the Adler hallmark. Over and over again she is cornered and forced to lash out (usually after seeking to document her case in a barrage of counterblasts of horrid length and unending dullness). This endgame always makes her bring the hammer down on her foes in no uncertain terms.

The book offers other rewards besides the joy of evisceration. For instance, Reckless Disregard also features in its coda a very brief but quite prescient reading of New York Times v. Sullivan, which, in 1964, established our current standard for libel law—that a publication must have acted in “actual malice” to defame a public figure. Four years later, “serious doubt” about a story’s trustworthiness was introduced as a loaded but ill-defined criterion for that malice. And so: “Publications, in order not to be vulnerable, in any future lawsuit to the charge that they had in fact, at any point in the writing or the publishing of a story, a ‘serious doubt,’ are beginning actively to discourage responsible inquiry, checking, editorial queries in the margin. . . . It is obvious that this interpretation encourages almost everything that is undesirable and unprofessional in journalism.”

And here we are today, with publications expressly instructing their “editors” not to edit—telling them that they may not touch the text before it is published—lest the publication bear legal responsibility instead of the author. What dystopias we all might live long enough to see!

As you can gather, Reckless Disregard is a bit like eating the ashes of a forest fire. I mean, delicious, sure! It is also an agony to read if you, like me, suffer from an inability to track more than three proper nouns, but its delights are bone-deep, like a manic session of nail-biting.

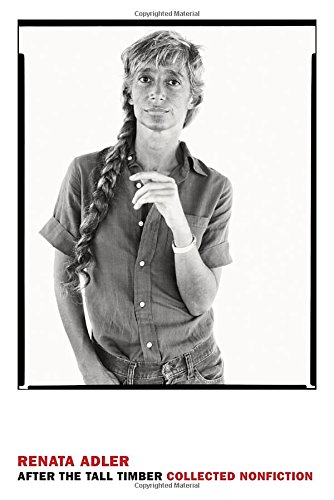

Nothing so nerve-racking appears in After the Tall Timber: Collected Nonfiction (New York Review Books, $30), a tidy yet daunting new anthology of Adler’s reportage. (It is not, it should be noted, a complete collection, but it is a solid one. Of the pieces missing in action, “The Thursday Group,” a long and destabilizing look at kinds of group therapy from 1967, is maybe one I’d have fought to include.) It tends to err on the side of the Most Important—an eminently forgivable tic for a writer such as Adler, who is now seeking to secure her written legacy with the imprimatur of the New York Review.

And so we have pieces like “Irreparable Harm,” on the matter of the garbage pit that was Bush v. Gore. And “Letter from Biafra,” wildly, sadly relevant now. The most important of these Most Important pieces, to my mind, is “Decoding the Starr Report”—also timely, since we are about to suffer a few seasons of Clintoniana and all the bullshit that entails. If you think you understand the story of Monica Lewinsky, Kenneth Starr, the FBI, and Linda Tripp, well, do you?

In the 1960s, J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI clandestinely made tapes of Martin Luther King Jr. engaged in various sexual acts in hotel bedrooms. The Bureau sent copies of those tapes to several public officials and members of the press, and to Dr. King himself, in order to humiliate him and either drive him to suicide or hound him into retirement. Judge Starr and his staff, in their failure to make a legal case, have resorted in the end to the same strategy. One difference is that their target is the President.

This piece ends with a nice post-publication hammering as well. And that coda is immediately followed by the greatest cornering of all. After the publication of Gone, Adler’s obituary for the New Yorker, the New York Times devoted eight stories to her—four of them about her “smear” of a dead man, the Watergate judge John J. Sirica, in that book. She addresses this in great detail. No one’s knives were ever sharper. Read it! Live it.

Of this collection’s preface, by her pal Michael Wolff, whatever. “Renata Adler has become something of a cult figure for a new generation of literary-minded young women” is how, somehow, he begins. Fifteen years ago, his line on her, for New York, was this: “When I came to New York in the early seventies, Adler was the young writer everybody talked about. She was The New Yorker’s ‘It’ girl. A sort of brainy Candace Bushnell, a bohemian Mia Farrow–ish Platonic ideal.” With friends like that, sheesh!

Choire Sicha is the author of Very Recent History (Harper, 2013).