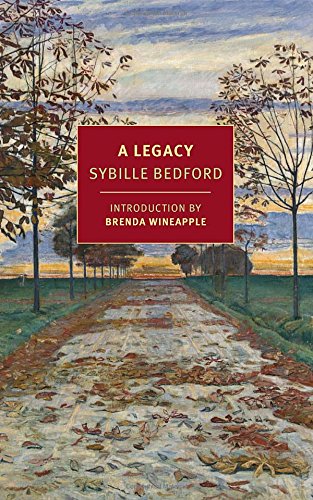

In A Legacy, first published in 1956, Sybille Bedford writes about a Germany in the years before the First World War that had almost disappeared even as it seemed to be in full bloom. This world of privilege and entitlement and eccentricity is presented as normal and natural and at a stage of rich development for those who inhabited it. But the author knows, and the reader too, that it is doomed.

The book is written in a style that is darting, confident, brisk, and brittle. The dialogue is close to that used by the English novelist Anthony Powell, who allowed his upper-class or socially ambitious characters to speak in clipped non sequiturs. It is like overhearing a conversation all the more fascinating because only some of it makes complete sense.

Aspects of the world brilliantly captured and dramatized by Bedford can also be found in novels such as Memoirs of an Anti-Semite (1979), by Gregor von Rezzori, in which the Europe of the early twentieth century seems close to its medieval and feudal roots, or Robert Musil’s The Confusions of Young Törless, first published in 1906, which deals with militarism and authority and cruelty in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The novel has some of the atmosphere of paintings by Otto Dix or Christian Schad or Max Beckmann, in which the characters depicted seem all angular and strange, with a faint or intense disturbance in their aura.

A Legacy, which has just been reissued by New York Review Books, is peopled by the rich and the ruling class, who are fraught and highly strung, and who have a special way of doing dark damage to each other, as though trained for it from birth. Chief among its protagonists is Baron Julius von Felden, from a landed Catholic family, who toward the end of the nineteenth century marries Melanie Merz, the daughter of a rich Jewish family in Berlin. The story, if story is the word—the novel is more a set of impressions or brilliantly created scenes—is what happens to the Feldens and the Merzes over the next decade. Bedford has enough tact and historical imagination to place the Merzes at the heart of the book while keeping at bay what will happen to such families under Hitler. She allows in only vague undercurrents of anti-Semitism; she makes the members of the Merz family too interesting and individual to be easily explained by history.

What makes A Legacy intriguing is not the social milieu, however, or even the characters themselves. Rather, it is the style of the book, its rhythmic energy. The reader can never guess how a sentence will end, or what is coming in the next phrase. Nothing obvious ever happens. Each image has been freshly chiseled, or rendered with a sparkling and glittering wit. Sarah, for example, “liked few people, had never loved and liked at the same time for long; she could not afford not to like herself. Dignity and conscience were her shell and her recourse. She had presence, she was instructed, she judged, she was too tall; men treated her as she appeared to them, and never, once, had she been spoken to in the way Julius spoke to Tzara, his chimpanzee.”

Her being “too tall” seems an odd addition to that list, as if it were a moral quality. Perhaps it is, or was then. And even though we already know that Julius speaks tenderly, indeed lovingly, to his chimpanzee—a brute that causes, by the way, particular havoc on a train as it crosses Europe—it seems peculiar that the relationship between Julius and the monkey is introduced here as the best example of something that poor Sarah does not experience. Surely she must have seen people being tender with each other? Perhaps not as intensely or meaningfully, however, as Julius and the chimp.

Bedford has particular skill at writing arresting openings and endings. For example, she begins a chapter: “When they had been in Spain for six months Jules bought a horse for Caroline.” And she ends that same chapter: “Two things leapt to her mind. The wording of the telegram was most peculiar. She was probably going to have a child.” It is up to us as readers to work out that the second thought may be more important than the first, but we also get something of the jumbled way that the mind works, or at least Caroline’s mind.

Slowly, as the book proceeds, it becomes clear that there is, in the re-creation of this world, a great deal at stake for Bedford. This perhaps explains the intensity of the novel’s tone, and the ways in which some scenes seem like fragments that have been reassembled, with dialogue that remains opaque and suggestive, like something reported later by someone who was listening from outside a half-open door.

[[img]]

Much of the book is, in fact, the story of Bedford’s own family in the years before her birth. She was born in Germany in 1911. When her parents divorced she lived first with her father in rural Austria and then in Italy with her mother and later in England and France. As a young woman, she became a close friend of Aldous Huxley and his wife. As a German citizen who had criticized Hitler, she was in some danger as war approached. She married Walter Bedford, who was gay, and thus got an English passport. Her first book was published in 1953, when she was forty-two.

The writer Conor Cruise O’Brien attempted to formulate the ways in which the past can haunt us and nourish us. “There is for all of us,” he wrote,

a twilight zone of time, stretching back for a generation or two before we were born, which never quite belongs to the rest of history. Our elders have talked their memories into our memories until we come to possess some sense of a continuity exceeding and traversing our own individual being. . . . Children of small and vocal communities are likely to possess it to a high degree and, if they are imaginative, have the power of incorporating into their own lives a significant span of time before their individual births.

Bedford made clear that A Legacy grew out of such a haunting, from what she managed to learn about the previous two generations of her family, which was then refracted over years in her imagination. “Thus what I know or feel I know,” she wrote, “about the places and the men and women in this story is derived from what I saw and above all heard and over-heard as a child at the age of roughly three to ten, much of which I managed to absorb, retain and decades after, to re-shape in an adult mode. The rest is invention and surmise.”

Bedford expanded on this in Quicksands, a memoir she published in 2005, the year before her death: “The sources of A Legacy (my first published novel) were the indiscretions of tutors and servants, the censures of nannies, the dinner-table talk of elderly members of a step-family-in-law, my own father’s tales, polished and visual; my mother’s talents for presenting private events in the light of literary and historical interpretation.”

The novel is filled with particularities—the precise atmosphere in a room or a hallway at one exact moment, or what someone said or remembered or noticed, or the view from a train, or the weather, or what a servant did, or how someone lost all their money. But it is also, in an odd and subtle and hidden way, a portrait of an age, a time when the rich could have an express train stopped in the middle of nowhere for their convenience, when people married unsuitably almost by necessity and then spent their lives dealing with the consequences, when every family seemed to have a mad uncle, or a cousin who was a powerful figure in government, when women spoke to one another in ways that were distant, embattled, and sometimes insulting.

Cut through this mixture of a family saga and an insider version of old-German entitlement are many strange stories. The most poignant deals with Johannes, an uncle who is forced to join the army. He does not, to say the least, take to military life, and his colleagues do not take to him: “That night in the dormitory they fell on him. They did not have an easy time of it, for Johannes was very strong. . . . He fought like a beast at bay—he sprang, he charged, he bit; he clawed, he bucked; but no one accused him of fighting like a girl, and what unnerved them most was the noise he made.” Bedford loves heaping up adjectives and phrases. The short sentence is just there for starters; she likes sentences that snake ahead and then spring to life and then look behind, and then dart suddenly in some new direction.

Against this story of cruelty and madness, ending eventually in violent death, is the story of the antics of Julius, a version of the author’s father. He is feckless, amusing, unsettled, dragging his first and second wives to France and Spain, filling his days with idleness and lassitude. The impressions of Caroline, a version of the author’s mother, are presented in whirling detail. When, for example, she gets two private carriages for herself and her maid on a Spanish train: “The night was milky, shot through with sudden lights; the countryside but outline. The train ran in and out of patches of darkness, charged walls sharp-angled as backdrops rearing near in relief and shadow, flew across a clearing: the sectioned, linear planes of a station yard.”

The writing here, as in much of the book, is all surface glitter. The characters are allowed to speak and see; they move about a great deal. They keep their inwardness to themselves. Bedford is too interested in what they do, what they seem like to others, what they say, and what she can do to her sentences, to be bothered dealing with the characters’ thoughts and reflections. Her genius is to make all this matter, to allow surface to suggest depth, to create excitement by playing with tone, to direct the reader toward the lives of her characters and the spirit of the age by using implication, by letting the rhythms do the work, by surprising with her diction and the texture of her prose and her dialogue. A Legacy makes clear that she is one of the finest and most original prose stylists of her age.

Colm Tóibín’s most recent novel is Nora Webster (Scribner, 2014).