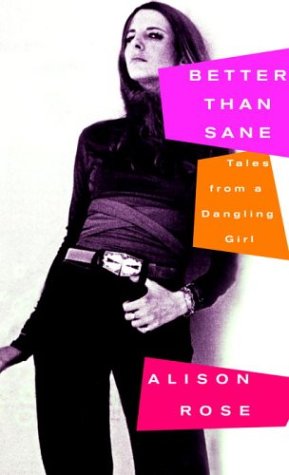

“IF YOU CANNOT GET RID OF the family skeleton, you may as well make it dance,” goes the only George Bernard Shaw quote I’ve ever bothered to fling around. Its best use may be for describing Alison C. Rose’s 2004 memoir, Better Than Sane: Tales from a Dangling Girl, where family—including, but not limited to, actual blood relatives—is a sort of game, and there is frankly little choice but to dance.

The impossibly resilient, delightfully lunatic Rose was one of the less buzzed-about writers of William Shawn’s sunset years at the New Yorker—a bit by her own design, we come to realize in these pages. Better Than Sane is the most radical anti-memoir I’ve read: no answers, no questions even, but instead a sort of anti-tribute to the art of finding one’s people, or thriving in the failure to do so.

We begin with Rose’s real family: Here is the brash psychiatrist father who threatens to have her committed, who calls all the women in the family a variation of “Babs” (no clues about why); a detached problem mother with an Oriental-object fetish who purrs, “Miss Jones, I presume,” when her daughters are at the door, a joke the sisters don’t get (neither do we). Everyone crushes on everyone else—boundaries? why?—mother’s friends on father, mother on sister’s boyfriends, sister’s boyfriends on Rose, Rose on them all. It somehow makes sense, then, that Rose’s first friendships come in the form of three mops (literally) and colored pencils (also literally).

Objects are safe, whereas humans are not, and the only thing that tethers Rose to her family is a desire for knowledge: “There was a total education right there in our house if anybody wanted it. Largely, this education consisted of men . . . and books.” And this paves the way for the central obsessions of the memoir: As she says, her father “was a bully and a tyrant and some kind of handsome star and completely depressed and droll. It stands to some kind of reason, then, that I might think a perfect boyfriend was a bully and tyrant and some kind of handsome star and completely depressed and droll.” Enter Harold Brodkey and George W. S. Trow, each embodying every NYC lit kid’s holy trinity of mentor, friend, and lover.

Her adult education is threefold—New York, the New Yorker, and the New Yorkers of the New Yorker—but is she looking for education or family? Or is one a stand-in for the other? After she is fired from her first job, at age forty-one, as a receptionist at the magazine, she is quickly hired as a Talk of the Town writer—and before you can think Rose slept her way there, she convinces you it was all due to Trow’s interest in her. Men come and go, as do eating disorders and Valium relapses.

When I first encountered this book, ten years ago, I was a young journalist living in the East Village. Like Rose, I was self-taught, not only in the book sense but also in the female sense, looking mainly to men I was involved with to light my path—while not believing in a path or even light, for that matter. Survival tossed with eccentricity plus youth: Anything was possible, and that was the problem. All I had—all Rose had, too—was dark humor and sunny irreverence. Confronted by the dogmas of the rat race, I distracted myself with the fact that we called the thing a rat race!

Whereas Renata Adler—who appears here in cameo, the ghost of a more sensible sister—flourishes by using knives and edges, Rose nicks with a lipstick pencil. But she wouldn’t have it any other way: Blood is not her sport, though neither is perfume. Hers is a sort of exuberant nihilism—a touch of Epicurus, a tad of Warhol, both advocates of the idea that coconspirators are the only real family—and these days, for me, it seems a refreshing model for how to survive. Here I am. Here are some friends, some lovers. Here is a job. Here is “sexually sexy sex” and beauty and obsession with all of it. Here is death, a thing we all do, a thing we do alone. What was the question again?

Porochista Khakpour is the author of Sons and Other Flammable Objects (Grove, 2007) and The Last Illusion (Bloomsbury, 2014).